The Rogue's March

The Rogue's March (also Poor Old Soldier, in some contexts Poor Old Tory or The Rogue's Tattoo) is a derisive piece of music, formerly used in the British, American and Canadian military for making an example of delinquent soldiers, typically when drumming them out of the regiment. It was also played during the punishment of sailors. Two different tunes are recorded; the better known has been traced back to a Cavalier taunt song originating in 1642. Unofficial lyrics were composed to fit the tune. The march was taken up by civilian bands as a kind of rough music to show contempt for unpopular individuals or causes, notably during the American Revolution. It was sometimes played out of context as a prank, or to satirise a powerful person. Historically The Rogue's March is the second piece of identified music known to have been performed in Australia.

Musical form[edit]

The Rogue's March could be played by the regimental fifers or trumpeters, as the case might be,[1][2] but these woodwind and brass instruments demanded different tunes.

Tune for fife[edit]

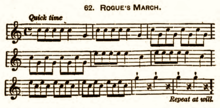

The best known tune was performed by fife and drum.[3] It was played in 6

8 time or, by a slight change of tune,[4] in 2

4 time. As many fifers and drummers as possible were assembled to play the ritual.[5]

In keeping with the ritual's purpose, the fife tune had a "derisory and childlike quality".[6] A British army punishment "since time immemorial", the tune shown here first appears in a fife book of 1756.[7] That a very similar tune was used in the American army, in the Indian wars at least, was attested by General Frank Baldwin[8] and corroborated by General Custer's widow.[9]

Rhythmic pattern[edit]

It appears that the march could be identified from the drumbeat alone; thus played, it was called the Rogue's Tattoo.[10] In one anecdote, members of a Scottish crowd recognised it when played by a solitary drummer,[11] as was done in the naval ritual of flogging round the fleet (see below).

Origins[edit]

Scholars have proposed that The Rogue's March can be traced to a taunt song called Cuckolds Come Dig, citing its analogous use for expelling prostitutes from Edinburgh earlier in the eighteenth century ('the whore's march').[7][12] In fact, this song was well known in connection with the English Civil War; in Sir Walter Scott's novel Woodstock a character quotes the words

Cuckolds,[13] come dig, cuckolds, come dig;

Round about cuckolds, come dance to my jig!

to insult Roundheads,[14] which rhythmic pattern has been said plausibly to fit the Rogue's March.[12] The song with those words originated in 1642/3 when Royalist soldiers taunted Londoners digging the defensive fortifications around the city.[15][16]

Tune for military trumpet or bugle[edit]

The military field trumpet, like the bugle, had no valves and could not play the notes of the diatonic scale[17] so a different tune had to be employed.

One such is known from America. By the end of the nineteenth century the bugle began to replace the traditional drummers and fifers for infantry use[18] and by World War I regulations the brass instrument was universal. The tune shown here appears in an 1886 manual[19] and again in Instructions for the Trumpet and Drum (Washington, 1915);[20] an American training manual for machine-gunners heading for World War I (facsimile reproduced);[21] and the U.S. Navy ship and gunnery drills 1927.[22]

An American version for cornet – a valved instrument – of 1874 used the fife version of the tune.[23]

Lyrics[edit]

Unofficial lyrics were fitted to versions of the tune; in the British army, perhaps as drinking songs.[24] A well known version was:[25]

Fifty [lashes] I got for selling me coat,

Fifty for selling me blanket.

If ever I 'lists[26] for a sodger again,

The Divil shall be me sergeant.

Poor old sodger, poor old sodger.

Twice tried for selling me coat,

Three times tried for desertion.

If ever I be a sodger again,

May the Divil promote me sergeant.

Poor old sodger, poor old sodger.

Another version:[27]

Went to a tavern and I got drunk

That is where they found me

Back to barracks in chains I was sent

And there they did impound me.

Fifty I got for selling me coat

Fifty I got for me blankets

If ever I 'list for a soldier again

The devil will be my sergeant.

In America, both Generals Frank Dwight Baldwin and Hugh Lenox Scott remembered the following lyrics from their days on the Indian frontier:[8][28]

Poor old soldier, poor old soldier

Tarred and feathered and sent to hell

Because he would not soldier well!

Other sources recall similar words, but no other lyrics are attested. The above are not long enough to match the tune. The illustration – from memoirs edited by General Custer's widow – recalls how it was done. The first 8 bars were played instrumentally; the voices joined in as a sort of chorus.

Military uses[edit]

British Army[edit]

Corporal punishment, when it could be administered in the British army of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, was inflicted by the military bandsmen, e.g.: drummers, to increase the ignominy. Hence it was commonplace for it to be accompanied by music.[29]

The Rogue's March was typically used for drumming out incorrigible offenders – often, those who stole from their comrades. The offender, after undergoing whatever additional punishment had been imposed, e.g.: a flogging, would be brought onto the parade-ground. Drummer boys would strip off his buttons and facings. The sentence would be read, the band would strike up the Rogue's March, and the offender would be marched through the ranks and out of the assembly and – in later practice – to a civilian jail.[30]

To increase the humiliation he might be kicked in the bottom by the smallest drummer boy,[3] and warned that he could expect severe punishment if he was seen there again. Sometimes a drummer boy led him with a halter [hangman's noose] around his neck. Soldiers' diaries record that the ritual made a very strong psychological impression on them.[6]

The punishment might also be employed on camp followers: "Thieves, strumpets, &c are frequently disgraced in this manner".[1]

By 1867 newspaper accounts could describe the procedure as "somewhat rare".[31][32][33] However, in 1902 two Aldershot soldiers who stole war medals awarded to black servicemen by King Edward VII in person were drummed out to the Rogue's March and thence to prison with hard labour, after the King himself had sent a telegram deprecating the disgrace.[34]

[edit]

Seamen were also drummed out of the Navy. One officer wrote that in a well run ship "the greatest punishment [is] to be turned out of the service with disgrace, and a bad certificate into the bargain", and citing two instances where he had had thieves "drummed out of the ship with the rough music of the Rogue's March", which put a stop to thieving.[35] Others were less enlightened. Several documents describe The Rogue's March being played to accompany flogging in the Navy.[36] Two accounts describe the extreme naval punishment known as flogging round the fleet where the march was played by a drummer boy placed in the bows of the boat as it passed from ship to ship.[37][38]

American forces[edit]

The same march with a similar ritual was used in the American army and militia.[40] In the 1812 war in one regiment "a soldier convicted of swindling had to forfeit half of his pay for two months, lose his liquor ration for the rest of the campaign, and – with his bayonet reversed and the right side of his face shaved close to the skin – be drummed up and down the lines to the Rogue's March three times".[41] A soldier in the Mexican war was ridden out of camp on a rail to its tune.[42] On the Texas frontier, recalled General Zenas Bliss, the usual penalty for desertion was fifty lashes "well laid on with a raw-hide" by the drummer-boys, after which his back was washed with brine; when he recovered, his head was shaved as closely as possible and he was drummed out to the fifes and drums of the Rogue's March.[43]

In the Civil War both sides used the punishment for cowardice or theft; the man's head would be shaved and a humiliating sign was hung on him; the march was played and he was drummed out.[44] On one occasion the entire Twentieth Illinois Volunteers ("a loose, rowdy bunch") was ordered to be marched off the parade ground – in the presence of other regiments – to the Rogue's March, which humiliated and infuriated the officers and men.[27] General Meade expelled a newspaper reporter by having him placed backwards on a mule and led through the ranks to the Rogue's March.[45] However the Rogue's March was also played at military executions by firing squad.[44][46] It was used in a black militia sent to maintain law and order in the South in the Reconstruction era.[47]

The expulsion could be lethal. An eyewitness recalled the practice during one of the Indian wars:

His head was shaved and he was branded with a hot iron and drummed out of the army. At that time it was suicide to go a mile from the fort, for the Indians watched the road constantly, but this did not seem to matter... [B]y February or March 1869, there had been four or five men drummed out of the Omaha Barracks. In each instance the men were branded with a hot iron, their heads were shaved, they were marched around the fort with a fife and drum playing "Poor Old Soldier", and then drummed out.[48]

In some cases the culprit's offence was placarded e.g. "Deserter: Skulked through the war"; "A chicken-thief'; "I presented a forged order for liquor and got caught at it"; "I struck a noncommissioned officer"; "I robbed the mail — I am sent to the penitentiary for 5 years". This practice was obsolete by 1920.[49][50]

In 1915 The Rogue's March was a prescribed item throughout the American Army, Navy and Marine Corps; the piece was "Played when a thief or other man is expelled the camp in disgrace".[51] It appeared in 1917 drill regulations for machine-gun companies heading for World War I,[21] and in 1927 drills in the Navy.[22]

It appeared from Winthrop's Military Law and Precedents (1920) that the playing of The Rogue's March during ignominious discharge was a punishment considered appropriate for enlisted men, not officers.[52]

Disuse[edit]

The last Marine to be drummed out to the Rogue's March – the ceremony was at Norfolk Marine Barracks and was attended by members of the public – was shown in Life magazine's Picture of the Week for April 20, 1962.[53] The same month General David M. Shoup, commandant of the U.S. Marine Corps, ordered Col. William C. Capehart, commander of the barracks to "knock off" drumming out disgraced Marines, a practice the latter had revived in 1960. "The local commander neither asked for nor was given authorization for the ceremony", said Shoup.[54]

By 1976 Chief Justice Burger referring to military disgrace could write: "The absence of the broken sword, the torn epaulets, and the Rogue's March from our military ritual does not lessen the indelibility of the stigma".[55]

A 1995 article in Air Force Law Review argued that drumming out to the Rogue's March ought to be revived and would be good for discipline, but the humiliation risked counting as cruel and unusual punishment within the meaning of the Eighth Amendment. To get round this the article suggested the culprit should be asked to sign a consent form.[56]

Canada[edit]

During World War II the Royal Canadian Regiment bugle band – which, having been officially disbanded, theoretically did not exist – smuggled its instruments ashore in the Allied invasion of Sicily. It was then reconstituted, duly performing the regimental music. "At a ceremonial promulgation of sixteen Courts-Martial, the culprits were drummed out of the regiment to the unhappy beat of the 'Rogue's March'.[57]

Australia[edit]

The First Fleet arrived in Botany Bay in 1788; the colony was officially proclaimed on 9 February;[58] on the 11th, three individuals were drummed out of the camp for fornication. Hence the first named piece of music known to have been performed in Australia – apart from God Save the King – was the Rogue's March.[59][60]

The Sudds-Thompson case was an event in the early history of New South Wales. In 1825 two soldiers, Sudds and Thompson, decided to steal from a shop and get caught on purpose, because they thought convicts had better long term prospects than soldiers. However the governor General Darling decided to make an example of them. According to Charles White's Convict life in New South Wales:[61]

The two men were stripped of their uniform and clothed in the convict dress; iron collars with long projecting spikes were then rivetted round their necks and fetters and chains rivetted on their legs. They were then drummed out of the regiment and marched back to gaol while the band played "The Rogue's March".

Whether Darling acted legally has been debated.[62] One of the men died and the case turned into a major political controversy.[63]

Rough music, subversion and pageantry[edit]

American Revolution[edit]

Like Yankee Doodle, British troops were known to play the Rogue's March to annoy troublesome colonial citizens.[64] When Paul Revere published a seditious cartoon a British regiment mustered outside the printer's shop: "With their colonel at their head and the regimental band playing the Rogue's March, they warned the publisher he would be next to wear a coat of tar and feathers".[65]

The colonials retaliated. Fife and drum bands often played the Rogue's March while Loyalists were manhandled by mobs.[66][67][68][69][70][71][72] One victim included Leigh Hunt's father[73] – a happening duly commemorated by the citizens of Philadelphia in a 1912 pageant.[74]

When Benedict Arnold was hanged in effigy for treachery his 'corpse' was carried in procession with fifes and drums playing the march.[75] And when the crowd pulled down the statue of George III in Bowling Green, New York, on 9 July 1776 they carried it off to the tune of the Rogue's March.[76]

A surviving manuscript shows the tune was also known as Poor Old Tory,[77] 'Tory' being another name for Loyalist.

Post-independence America[edit]

During the Federalist-Republican struggles of the 1790s the Rogue's March was used as rough music to harass Federalist congressmen.[78] Fifers and drummers played it under Thomas Jefferson's windows at a time when he was deeply unpopular.[79] When vice-president Aaron Burr was acquitted of treason in 1807, a Baltimore mob hanged him (together with presiding Chief Justice Marshall) in effigy while a band played the Rogue's March.[80] At the 1868 Republican National Convention a brass band played Hail to the Chief for candidate Ulysses S. Grant but the Rogue's March for the "seven traitors" (the Republican senators who voted against the impeachment of Andrew Johnson).[81]

The march was also associated with mob violence. In some labour disputes in nineteenth century America unpopular masters might hear drum and fife bands playing the Rogue's March as a prelude to tarring and feathering or riding out on a rail.[82] During the anti-abolitionist riots of 1834, in Norwich, Connecticut

the mob entered a church during the delivery of an abolition sermon, took the parson from the pulpit, walked him into the open air to the tune of the "Rogue's March", drummed him out of the town, and threatened if he ever made his appearance in the place again they would give him " a coat of tar and feathers."[83]

In 1863 the Washington DC police "rounded up a batch of thieves, pickpockets, and prostitutes, many from the Murder Bay area. Then they herded the culprits down Pennsylvania Avenue to the train station and out of the city, appropriately followed by a brass band serenading the gathering with The Rogue's March."[84]

United Kingdom[edit]

In the mutiny of the Nore (1797) rebellious seamen seized a boatswain and, in a parody of the naval punishment, rowed him round the Fleet while a drummer beat the Rogue's March.[85]

Those burned in effigy while bands played the Rogue's March have included:

- Guy Fawkes (for trying to destroy the Protestant monarchy).[86]

- Thomas Paine (frequently, for writing the Rights of Man)[87]

- Thomas Babington Macaulay (for offending Highlanders in his History of England),[88] and

- Cardinal Wiseman[89] and Pope Pius IX (for restoring the Catholic hierarchy in England).[90]

Satire or pranking[edit]

The Rogue's March concept has often been used for satirical purposes, especially during the Napoleonic Wars.

On 17 March 1735 John Barlow, organist of St Paul's Church, Bedford, was dismissed for playing The Rogue's March while the Mayor and Aldermen were processing down the aisle.[91]

In March 1825 in Union, Maine, Captain Lewis Bachelder was court-martialled for letting the regimental band strike up The Rogue's March when their colonel entered.[92]

In literature and popular culture[edit]

The expression "to face the music" (to confront the unavoidable) may derive from the Rogue's March ritual, though there are alternative theories.[10]

The Rogue's March: A Romance, a novel by E. W. Hornung (author of the Raffles stories), is set in Australia and was in part inspired by the Sudds-Thompson case mentioned in this article.[93]

In the monologue "Sam Drummed Out". written in 1935 by R.P Weston and Bert Lee and most notably performed by Stanley Holloway, Private Sam Small is court-martialed for "maliciously putting cold water in beer in the Sergeants' canteen." When he refuses to defend himself, he is found guilty and "drummed out": "Then the drums and the pipes played the Rogues March/ And the Colonel he sobbed and said, 'Sam,/ You're no longer a Soldier, I'm sorry to say/ Sam, Sam, you're a dirty old man.'"[94]

Rogue's March is a 1953 American film in which a British officer is falsely accused of treason and drummed out of the regiment.

Rogue's March (1982) is a noir spy novel by "W. T. Tyler" (Samuel J. Hamrick) about a CIA officer in Central Africa.[95]

In the television adaption of Sharpe's Eagle, the Rogue's March is played at the very beginning of the film when the South Essex first appears marching. It is also played ironically when Major Lennox (Captain in the book) under orders from Colonel Sir Henry Simmerson leads a company to chase off a small French patrol, an action that the major knows is a fool's errand; he is quickly proven right when the company is ambushed by French cavalry, costing Lennox his life. The song is also sung by John Tams (who played "Rifleman Daniel Hagman" in the series) and Barry Coope on the companion album Over the Hills & Far Away: The Music of Sharpe

Rogue's March is a 1999 album by punk rock band American Steel.

See also[edit]

Notes[edit]

- ^ a b James 1816, p. 475.

- ^ In the British army of the Napoleonic war era the infantry used the fife while cavalry used the trumpet (James, 1816, p.397). In the United States fifes were traditional but were gradually replaced by trumpets or bugles (Dobney, 2004).

- ^ a b Grant 2013, pp. 14–15.

- ^ Rutherfoord 1756, p. 14.

- ^ Lancaster 2015, p. 416.

- ^ a b Herbert & Barlow 2013, p. 223.

- ^ a b Herbert & Barlow 2013, p. 224.

- ^ a b Baldwin 1929, pp. 154–5.

- ^ Custer 1890, pp. xi, 147.

- ^ a b OED 2019.

- ^ Brechin Advertiser 1957, p. 6.

- ^ a b Nourse 2012.

- ^ An insulting expression, implying that a man's wife cheated him.

- ^ Scott 1826, p. 142.

- ^ Brett-James 1928, pp. 1–11.

- ^ Pyne 1825, p. 352.

- ^ Instructions for the trumpet &c 1915, pp. 7, 8.

- ^ Dobney 2004.

- ^ Bugle, Fife and Drum Signals 1887, pp. 3, 16.

- ^ Instructions for the trumpet &c 1915, p. 34.

- ^ a b Machine-gun drill regulations 1917, p. 257.

- ^ a b Ship and gunnery drills 1927, pp. 318, 345.

- ^ Ryan 1874, p. 55.

- ^ Fischer 1995, p. 71.

- ^ Latimer 2009, p. 258.

- ^ Enlists.

- ^ a b Jamison 2009, p. 127.

- ^ Scott 1928, p. 45.

- ^ Grant 2013, p. 9.

- ^ Grant 2013, p. 14.

- ^ Berkshire Chronicle 1867, p. 2.

- ^ Portsmouth Times 1867, p. 4.

- ^ Norwich Mercury 1902, p. 2.

- ^ Gourly 1838, pp. 59–60.

- ^ Grant 2013, p. 16.

- ^ Anon 1838, p. 230.

- ^ Leech 1844, pp. 61–62.

- ^ Forbes 1890, p. 303.

- ^ Benét 1863, p. 168.

- ^ Mahon 1951, p. 424.

- ^ Robertson 1849, p. 93.

- ^ Bliss 1906, p. 125.

- ^ a b Abel 2000, pp. 148–150.

- ^ Davis 1982, p. 400.

- ^ Malone 1982, p. 119.

- ^ Singletary 1955, p. 181.

- ^ Cozzens 2001, pp. 73–74.

- ^ U.S. v. Cruz 1987, p. 330.

- ^ Kunich 1995, pp. 48–9.

- ^ Instructions for the trumpet &c 1915, pp. 21, 34.

- ^ Kunich 1995, p. 48.

- ^ Life 1962, p. 3.

- ^ Owosso Argus-Press 1962, p. 15.

- ^ Department of Air Force v. Rose 1976, p. 384.

- ^ Kunich 1995, pp. 48, 50–6.

- ^ Bands in the Canadian Army 1986, p. 20.

- ^ Becke & Jeffery 1899, p. 52.

- ^ Lancaster 2015, pp. 415–6.

- ^ See also Grant (2013), p.14, citing Nourse, 2012.

- ^ White 1889, p. 80.

- ^ Connor 2009. (Connor had developed the materials for his article, in greater detail, in an earlier PhD thesis: Connor 2002.)

- ^ Bennett 1865, pp. 598–603.

- ^ Myers 1849, pp. 84, iii–vii.

- ^ Fischer 1995, p. 72.

- ^ Brooke 1843, p. 7.

- ^ Siebert 1920, p. 23.

- ^ Van Tyne 1929, p. 230.

- ^ Connolly 1889, pp. 26, 28.

- ^ Sabine 1864, pp. 236, 597.

- ^ Steiner 1902, p. 44.

- ^ Miller 1948, p. 446.

- ^ Hunt 1903, p. 8.

- ^ Williams 1912, p. 39.

- ^ Todd 1903, p. 224.

- ^ Hoock 2017, p. 107.

- ^ Beck 1786.

- ^ Wood 2014, p. 1083.

- ^ Fleming 1971, p. 110.

- ^ McManus & Helfman 2013, p. 131.

- ^ Hill 1868, p. 171.

- ^ Davis 1985, p. 112.

- ^ De Fontaine 1861, p. 29.

- ^ Press 1984, pp. 57–8.

- ^ Cunningham 1829, p. 14.

- ^ London Evening Standard 1850, p. 4.

- ^ Dozier 2015, p. 91.

- ^ Liverpool Daily Post 1856, p. 3.

- ^ Ward 1897, p. 551.

- ^ Paz 1992, pp. 235–6.

- ^ Henman 1940, p. 10.

- ^ Sibley 1851, pp. 365–6.

- ^ Hornung 1896, pp. vii–viii.

- ^ "Sam Drummed Out". monologues.co.uk. Retrieved 27 September 2022.

- ^ Fletcher 1987, pp. 327–8.

Sources[edit]

Books and journals[edit]

- Abel, E. Lawrence (2000). Singing the New Nation. Stackpole Books. ISBN 0811746763.

- Anon (1838). "Flogging Scenes Aboard a Man-of-War". Tales of the Wars; or, the Naval and Military Chronicle. Vol. 2. London: William Mark Clark. Retrieved 8 May 2019.

- Baldwin, Alice Blackwood (1929). Brown, Brigadier General W. C.; Smith, Colonel C. C.; Brininstool, E. A. (eds.). Memoirs of the late Frank D. Baldwin, major general, U. S. A. Los Angeles, CA: Wetzel Publishing Co., Inc. Retrieved 2 May 2019.

- Beck, Henry (1786). "Flute Book (1786)". Retrieved 27 April 2019.

- Becke, Louis; Jeffery, Walter (1899). Admiral Phillip: The Founding of New South Wales. London: T. Fisher Unwin. Retrieved 8 May 2019.

- Benét, Stephen Vincent (1863). A Treatise on Military Law and the Practice of Courts-martial (3 ed.). D. Van Nostrand. Retrieved 8 May 2019.

- Bennett, Samuel (1865). The History of Australian Discovery and Colonisation, Part 4 (2 ed.). Sydney: Hanson & Bennett. Retrieved 8 May 2019.

- Bliss, Zeldas (1906). "Types and traditions of the old army: Extracts from the unpublished memoirs of Major-General Zenas R. Bliss, U.S.A". In Rodenbough, Brig. General T. F. (ed.). Journal of the Military Service Institution of the United States. Vol. XXXVIII. Governor's Island: Military service Institution. Retrieved 4 May 2019.

- Brett-James, Norman G. (1928). "The Fortification of London in 1642/3". In Godfrey, Walter H. (ed.). London Topographical Record. Vol. XIV. London Topographical Society. Retrieved 4 May 2019.

- Brooke, Henry K. (1843). Annals of the Revolution: or, A history of the Doans. Philadelphia: John B. Perry. Retrieved 8 May 2019.

- Bugle, Fife and Drum Signals and Calls as used in the Regular Army and Militia of the United States. Boston: Oliver Ditson & Co. 1887. Retrieved 5 May 2019.

- Connolly, John (1889). A narrative of the transactions, imprisonment, and sufferings of John Connolly, an American loyalist, and lieutenant-colonel in His Majesty's service. New York: C. L. Woodward. Retrieved 8 May 2019.}

- Cozzens, Peter, ed. (2001). Eyewitnesses to the Indian Wars, 1865-1890: The long war for the Northern Plains. Vol. 4. Stackpole Books. ISBN 0811705722.

- Connor, MichaeL C. (2002). The politics of grievance : society and political controversies in New South Wales, 1819-1827 (PhD). Retrieved 14 June 2020.

- Connor, Michael (1 September 2009). "Rogue History". Quadrant Online. Retrieved 30 April 2019.

- Cunningham, Charles, Sir (1829). A narrative of occurrences that took place during the Mutiny at the Nore, in the months of May and June, 1797; with a few observations upon the impressment of seamen, and the advantages of those who are employed in His Majesty's Navy; also on the necessity and useful operations of the articles of war. Chatham: W. Burrill. Retrieved 8 May 2019.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Custer, Elizabeth Bacon (1890). Following the Guidon. New York: Harper. Retrieved 4 May 2019.

- Davis, Stephen (1982). "Sherman's Other War: The General and the Civil War Press by John F. Marszalek". The Georgia Historical Quarterly. 66 (3). Georgia Historical Society: 400–401. JSTOR 40580950.

- Davis, Susan G. (1985). "Strike Parades and the Politics of Representing Class in Antebellum Philadelphia". The Drama Review: TDR. 29 (3). MIT Press: 106–116. doi:10.2307/1145657. JSTOR 1145657.

- De Fontaine, F. G. (1861). History of American abolitionism; its four great epochs, embracing narratives of the ordinance of 1787, compromise of 1820, annexation of Texas, Mexican war, Wilmot proviso, Negro insurrections, abolition riots, slave rescues, Compromise of 1850, Kansas bill of 1854, John Brown insurrection, 1859, valuable statistics, &c., &c., &c., together with a history of the southern confederacy. New York: Appleton. Retrieved 8 May 2019.

- Department of Air Force v. Rose (1976). 425 U.S. 352 (PDF). U.S. Supreme Court. Retrieved 30 April 2022.

- Dobney, Jason Kerr (October 2004). "Military Music in American and European Traditions". Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History. The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Retrieved 4 May 2019.

- Dozier, Robert (2015). For King, Constitution, and Country: The English Loyalists and the French Revolution. University Press of Kentucky. ISBN 978-0813162713.

- Fischer, David Hackett (1995). Paul Revere's Ride. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0199779651.

- Fleming, Thomas J. (1971). Thomas Jefferson. Grosset & Dunlap. ISBN 044821413X.

- Fletcher, Katy (1987). "Evolution of the Modern American Spy Novel". Journal of Contemporary History. 22 (2). Sage Publications: 319–331. doi:10.1177/002200948702200206. JSTOR 260935.

- Forbes, Edwin (1890). Thirty years after. An artist's story of the great war, told, and illustrated with nearly 300 relief-etchings after sketches in the field, and 20 half-tone equestrian portraits from original oil paintings. New York: Fords, Howard, & Hulbert. Retrieved 8 May 2019.

- Grant, M.J. (2013). "Music and Punishment in the British Army in the Eighteenth and Nineteenth Centuries". The World of Music. New Series. 2 (1). VWB - Verlag für Wissenschaft und Bildung: 9–30. JSTOR 24318194.

- Gourly, John (1838). On the great evils of impressment, and its mischievous effects in the royal navy and the merchant ships, with the great benefits to the seamen, bestowed by the registration act, of the 30th July, 1835. Southampton: John Wheeler. Retrieved 8 May 2019.

- Herbert, Trevor; Barlow, Helen (2013). Music & the British Military in the Long Nineteenth Century. Oxford University Press USA. ISBN 978-0199898312.

- Hill, Adams Sherman (1868). "The Chicago Convention". The North American Review. 107 (220). University of Northern Iowa: 167–186. JSTOR 25108197.

- Hoock, Holger (2017). Scars of Independence: America's Violent Birth. Crown/Archetype. ISBN 978-0804137294.

- Hornung, E.W. (1896). The Rogue's March: A Romance. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons. Retrieved 6 May 2019.

- Hunt, Leigh (1903). The autobiography of Leigh Hunt, with reminiscences of friends and contemporaries, and with Thornton Hunt's introduction and postscript, newly edited by Roger Ingpen. New York: E. P. Dutton & Co. Retrieved 8 May 2019.

- Instructions for the trumpet and drum, together with the full code of signals and calls used by the United States Army, Navy and Marine Corps. Washington: Government Printing Office. 1915. Retrieved 8 May 2019.

- James, Charles (1816). A Universal Military Dictionary in English and French: In which Are Explained the Terms of the Principal Sciences that are Necessary for the Information of an Officer (4 ed.). T. Egerton at the Military Library. Retrieved 8 May 2019.

- Jamison, King Wells (2009). "North and South at Britton's Lane, September 1862: Looking in a Different Direction". Tennessee Historical Quarterly. 68 (2). Tennessee Historical Society: 114–129. JSTOR 42628123.

- Kunich, John C. (1995). "Drumming out Ceremonies: Historical Relic or Overlooked Tool". Air Force Law Review. 39: 47–56. Retrieved 29 April 2022.

- Lancaster, Geoffrey (2015). The First Fleet Piano: Volume One: A Musician's View. Vol. 2. ANLI Press. ISBN 978-1922144652.

- Latimer, John (2009). 1812: War with America. Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0674039957.

- Leech, Samuel (1844). Thirty years from home; or A voice from the main deck being the experience of Samuel Leech, who was for six years in the British and American navies; was captured in the British frigate Macedonian; afterwards entered the American navy, and was taken in the United States brig Syren, by the British ship Medway. Boston: C. Tappan. p. 62. Retrieved 8 May 2019.

- Mahon, John K. (1951). "The Carolina Brigade Sent Against the Creek Indians in 1814". The North Carolina Historical Review. 28 (4). North Carolina Office of Archives and History: 421–425. JSTOR 23515872.

- McManus, Edgar J.; Helfman, Tara (2013). Liberty and Union: A Constitutional History of the United States. Vol. 1. Routledge. ISBN 978-1136756672.

- Malone, Bill C. (1982). "Music and Musket: Bands and Bandsmen of the American Civil War by Kenneth E. Olson". The Journal of Southern History. 48 (1). Southern Historical Association: 118–119. doi:10.2307/2207319. JSTOR 2207319.

- Miller, John Chester (1948). Triumph of freedom, 1775-1783. Boston: Little, Brown. Retrieved 8 May 2019.

- Myers, Ned (1849). Cooper, James Fenimore (ed.). Ned Myers, or A Life Before the Mast. New York: Stringer & Townsend. Retrieved 5 May 2019.

- Nourse, Nick (2012). "Australia's First (British) Musical Import: The Rogue's March". CHOMBEC News (Centre for the History of Music in Britain, the Empire and the Commonwealth). 13. University of Bristol: 1–3.

- Oxford English Dictionary Online. Oxford University Press. Retrieved 22 April 2019.

- Paz, Denis G. (1992). Popular Anti-Catholicism in Mid-Victorian England. Stanford University Press. ISBN 0804719845.

- Press, Donald E. (1984). "South of the Avenue: From Murder Bay to the Federal Triangle". Records of the Columbia Historical Society, Washington, D.C. 51. Historical Society of Washington, D.C.: 51–70. JSTOR 40067844.

- Pyne, W. H. (Ephraim Hardcastle [pseud.]) (1825). The Twenty-ninth of May: Rare Doings at the Restoration. London: Knight and Lacey. Retrieved 4 May 2019.

- Robertson, John Blout (1849). Reminiscences of a campaign in Mexico; by a member of "the Bloody-First." Preceded by a short sketch of the history and condition of Mexico from her revolution down to the war with the United States. Nashville TN: J. York & Co. Retrieved 8 May 2019.

- Rutherfoord, (attrib.) (1756). The Compleat Tutor for the Fife, Containing the Best & Easiest Instructions to Learn that Instrument, with a Collection of Celebrated March's & Airs Perform'd in the Guards & Other Regiments &c. London: S. Thompson. Retrieved 8 May 2019.

- Ryan, Sidney (1874). Ryan's true cornet instructor: containing concise instructions, compass, capabilities, and illustrations, together with rules, exercises, studies, and a large collection of popular music. Cincinnati: J. Church & Co. Retrieved 8 May 2019.

- Sabine, Lorenzo (1864). Biographical sketches of loyalists of the American Revolution with an historical essay. Boston: Little, Brown. Retrieved 8 May 2019.

- Scott, Walter, Sir (1826). Woodstock; or, The Cavalier. A tale of the year sixteen hundred and fifty-one. Edinburgh: A. Constable.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Scott, Hugh Lenox (1928). Some memories of a soldier. New York: The Century Co. Retrieved 2 May 2019.

- Ship and gunnery drills, United States Navy. Washington DC: Government Printing Office. 1927. Retrieved 8 May 2019.

- Sibley, John Langdon (1851). A history of the town of Union, in the county of Lincoln, Maine: to the middle of the nineteenth century. Boston: Benjamin B. Mussey & Co. Retrieved 8 May 2019.

- Siebert, William H (1920). "The Loyalists of Pennsylvania". The Ohio State University Bulletin. XXIV (23). Retrieved 8 May 2019.

- Singletary, Otis A. (1955). "The Negro Militia During Radical Reconstruction". Military Affairs. 19 (4): 177–186. doi:10.2307/1982316. JSTOR 1982316.

- Steiner, Bernard C. (1902). "Western Maryland in the Revolution". Johns Hopkins University Studies in Historical and Political Science. XX (1). Baltimore, MD: The Johns Hopkins Press. Retrieved 8 May 2019.

- The Army War College, ed. (1918). Machine-gun drill regulations: provisional 1917. US Government Printing Office. Retrieved 8 May 2019.

- The History of Bands in the Canadian Army (Report No. 47: Historical Section (G.S.) Army Headquarters (PDF). Ottawa: Government of Canada. 12 November 1986. Retrieved 4 May 2019.

- Todd, Charles Burr (1903). The real Benedict Arnold. New York: A.S. Barnes and Company. Retrieved 8 May 2019.

- U.S. v. Cruz (1987). 25 M.J. 326 (PDF). U.S. Court of Military Appeals. Retrieved 30 April 2022.

- Van Tyne, Claude Halstead (1929). The Loyalists in the American revolution. New York: P. Smith. Retrieved 8 May 2019.

- Ward, Wilfrid (1897). The Life and Times of Cardinal Wiseman. Vol. 1. London: Longmans, Green & Co.

- White, Charles (1889). Convict Life in New South Wales and Van Diemen's Land; Parts I and II. Bathurst: C. & G.S White. Retrieved 6 May 2019.

- Williams, Francis Howard (1912). Official pictorial and descriptive souvenir book of the historical pageant, October seventh to twelfth, 1912. Philadelphia: Historical pageant committee of Philadelphia. Retrieved 8 May 2019.

- Wood, Kirsten E. (2014). ""Join with Heart and Soul and Voice": Music, Harmony, and Politics in the Early American Republic". The American Historical Review. 119 (4): 1083–1116. doi:10.1093/ahr/119.4.1083. JSTOR 43695886.

Newspaper and magazine reports[edit]

- "The Fifth of November Demonstration". London Evening Standard. 7 November 1850.

- "Macaulay Burnt in Effigy in the Highlands". Liverpool Daily Post. 1 March 1856. p. 3.

- "Drummed Out". Portsmouth Times and Naval Gazette. 23 November 1867.

- "Drumming Out". Berkshire Chronicle. 23 November 1867.

- "Infantry". Naval & Military Gazette and Weekly Chronicle of the United Service. 23 November 1867.

- "Stolen War Medals: The Thieves Drummed Out of the Army". Norwich Mercury. 30 August 1902.

- Henman, W.N. (9 February 1940). "Eighteenth century organists at St Paul's, Bedford: the "notorious behaviour" of John Barlow". Bedfordshire Times and Standard. p. 10.

- "The March to Taranty Fair". Brechin Advertiser. 3 September 1957. p. 6.

- "DOLEFUL DRUMS FOR AN OUTCAST". Life. 20 April 1962. Retrieved 7 May 2019.

- "Orders Halt to Drumming Out of Disgraced Marines". The Owosso Argus-Press. 9 April 1962. Retrieved 6 May 2019.

External links[edit]

- The Rogue's March (fife version) played by the Band of the Royal Military School of Music & Kneller Hall.

- The Rogue's March (bugle version). Played in 1908 by the cornets and trumpets of Arthur Pryor's band. (Track 2: at 01:49/03:06.)

- The last man to be drummed out of the US Marine Corps to the Rogue's March (photo in Life Magazine.