Chapel of Saint-Jean du Liget

| Chapel of Saint-Jean du Liget | |

|---|---|

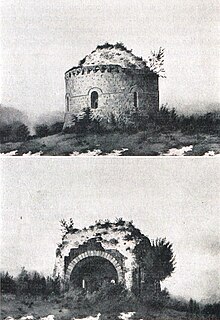

View of the chapel. | |

| Religion | |

| District | Sennevières |

| Province | Indre-et-Loire |

| Region | Centre-Val de Loire |

| Location | |

| Country | France |

| Architecture | |

| Completed | 17th century |

The chapel of Saint-Jean du Liget, or chapelle Saint-Jean-du-Liget or chapelle du Liget, is an ancient chapel located in the commune of Sennevières, in the Indre-et-Loire department of France.

It was probably built around the middle of the 11th century, although this dating is still debated to within a few decades, which maintains the uncertainty as to which monastic order, Benedictine or Carthusian, founded it. Similarly, its dedication to Saint John, which could apply to another monument, is disputed. Until the French Revolution, it was attached to the Liget Carthusian monastery, when, already in ruins, it was sold to private owners and then to the State. The latter undertook its restoration in the 1860s, after it was classified as a monument historique in 1862. The chapel has been owned by the commune of Sennevières since 2007.

Its unique initial layout (rotunda preceded by a nave) is reminiscent of the Church of the Holy Sepulchre in Jerusalem, as discovered by the first Crusaders. The interior walls of this chapel's rotunda - the only part of the monument to have been preserved, which also had a nave - were covered with Romanesque polychrome frescos, the surviving ones depicting figures of saints and major biblical scenes from the Marian cycle. These frescos are among the best-preserved medieval frescoes in the Indre-et-Loire region, although they are tending to deteriorate. It is for this reason that the chapel is closed to the public, except on exceptional occasions.

Location and toponymy[edit]

The chapel is located on the border between the communes of Chemillé-sur-Indrois and Sennevières, but on the territory of the latter. It is less than 900 m south-west of the Chartreuse du Liget, of which it was a dependency, and 150 m south-east of the D760 (route from Loches to Montrésor), these distances being expressed as the crow flies. Until perhaps the 17th century, this road took a different route, passing to the south of the chapel.[1]

The chapel is located in the heart of the Loches forest, in a clearing with a former tile factory, also attached to the Carthusian monastery; all these buildings occupy the bottom and slopes of the same Vallon.[2] A fountain near the chapel was the object of pilgrimage until 1870.[3]

The building is oriented from south-west (the former nave) to north-east (the rotunda's "axial" bay).[4]

The origin of the toponym "Liget" is not attested for the Touraine chapel and chartreuse; it appears under the name Ligetum in a charter of 1172.[5] However, Albert Philippon, citing an older document in 1934, suggests that Liget may be a deformation of the word lige, indicating a form of dependency[6] between this land and the mother abbey of Villeloin, to which it originally belonged.[2]

The church's dedication to St. John remains a matter of debate. It is based on the interpretation of a 14th-century text, but another reading envisages that the dedication actually applies to the Corroirie church;[7] the representation of Saint John in the chapel's decor is far from attested.[8] Nevertheless, in common parlance, this round chapel remains the chapelle Saint-Jean.

History[edit]

The circumstances surrounding the founding of the Carthusian monastery and the construction of the Liget chapel are still debated, due to the many possible interpretations of the sources. The history of the chapel, as presented here, is that towards which the most recent and comprehensive studies tend; it remains a proposal, subject to refinement or contradiction in the light of subsequent work.[9]

First eremitic foundation[edit]

Surveys carried out in 1998, which led to the discovery of ceramics from the 11th and 12th centuries, seem to indicate that the site was occupied before the chapel[10] was built; in 1980, Raymond Oursel had already reported the presence of these medieval artifacts on the surface.[11] It is possible that very early on, hermits, perhaps Benedictines from the Villeloin abbey, settled on the site, which came under the jurisdiction of their abbey.

The land at Le Liget appears to have been purchased from Villeloin abbey by Henry II between 1176 and 1183, and then given to this small community on condition that it join the Chartreux order,[12] as may have happened a few kilometers away, under the aegis of the same sovereign, to the Cistercian abbey of Beaugerais around 1150[13] and the Grandmontain priory of Villiers around 1160-1170.[14] The purpose of these land transactions was probably to stabilize new religious[15] communities while seeking to counterbalance the dominance of the Cluniac Benedictines in the region by promoting emerging monastic orders.[16][17]

Benedictine or Carthusian chapel[edit]

The date on which the chapel was built, and the monastic order that built it, are the subject of much debate. Some authors attribute the building to the Carthusian monks of Le Liget, after 1150 - such as Dom Étienne Housseau in the 18th century[18] - while others believe it was built by the Benedictines of Villeloin in the first half of the 11th century, before the estate was donated to the Carthusians.[19] Construction most probably began with the rotunda, followed shortly afterwards by the nave, whose masonry partially obliterated the frames of certain bays.[20][21]

The dating of the frescos is also uncertain. After initially proposing, like others,[22] a "low" dating towards the end of the 11th century, historian Christophe Meunier revised his assessment, dating the frescoes to the end of the first half of the 11th century,[23] in agreement with Voichita Munteanu, an art historian who has devoted a thesis to the study of these paintings;[24] in their view, this work is more in keeping with Cluniac pomp than with Carthusian rigor.[25] In addition, Dom Willibrord Witters mentions that in 1280, a decision of the Carthusian General Chapter ordered the "disappearance" of the Liget paintings. This recommendation, which was not acted upon, is hardly conceivable if the Carthusian monks themselves were the authors of these frescoes; it becomes more understandable if they were the Benedictine hermits of the early years.[16] In any case, it seems that the decorations were all painted once the chapel, rotunda and nave[26] were fully completed. Robert Favreau, for his part, based on a graphological study of the inscriptions, believes that the frescos were painted around 1170-1180.[8]

Possible monastery church, then simple chapel[edit]

Ancient documents, and in particular an extract from a 15th century obituary (although the document is imprecise and suffers from chronological[27] errors), suggest that the chapel first served as a church for the Carthusian monastery's upper house (where the fathers devoted to studying and copying books lived), then for the Corroirie (lower house where the brothers responsible for manual and agricultural work lived), until the latter acquired its own church[5] in the 13th century. It is even possible that the Carthusian monks initially planned to build their upper house around this chapel, which would explain the extension of the building by adding a nave, before changing their minds for unknown reasons.[28]

Early abandonment[edit]

The chapel was probably abandoned in the 16th century.[30] Two watercolors painted in 1850 by Aymar Pierre Verdier show it in a state of disrepair, with the roof missing, revealing the dome of the cupola, the west facade gaping, and the walls overgrown with vegetation.[31] In 1862, the chapel was listed as a monument historique.[32] Major restorations were then undertaken under the direction of Verdie.[33] It is not known[34] when the nave preceding the rotunda to the west was demolished, but it was before 1850, as this part of the chapel no longer appears in the watercolors produced by this date.[33]

Owned by the Carthusian monks of Le Liget until the French Revolution, the chapel then belonged to private owners, including the family who also owned the Carthusian[30] monastery, until 1851.It then became the property of the State,[35] which sold it in 2007 to the commune of Sennevières,[36] which delegated its tourist management to the Loches Développement community of communes (Communauté de communes Loches Sud Touraine since 2017).[37]

The frescos were restored twice, first between 1851 and 1925, and then in the 1960s.[38] In 2009, the frescos were restored under the supervision of Arnaud de Saint-Jouan, the architect responsible for French buildings.[39] To prevent deterioration, the chapel is only exceptionally open to the public, while a gate behind the door prevents access to the rotunda.

Architecture and decoration[edit]

Chapele[edit]

The chapel consists of a circular rotunda, preceded to the west by a nave that disappeared at some undetermined time. All that remains is the start of the gutter walls in contact with the rotunda. The large arcade linking the nave to the rotunda was closed off in the 19th century, and the resulting diaphragm wall was pierced by a semicircular door. The rotunda is lit by seven non-equidistant round-headed windows, averaging 1.50 × 0.40 m in size.[40] The bay that can be considered axial, opposite the door, is slightly wider, perhaps to accommodate a stone altar[41] underneath, which was replaced by a wooden one in 1697.[42] A niche, perhaps a washbasin, is cut into the wall beneath one of the windows.[43] The base of these windows is approximately 2 m above ground level.[44] A molding runs halfway up the wall of the rotunda, highlighting the arches of the bays; the wall below this molding marks a slight rise.[45] All that is left are the remains of the porch or room, perhaps a sacristy,[46][30] which preceded the doorway to the south of the rotunda.[47] Although the function of the massive masonry wall framing this door is not yet clear, some historians refute the hypothesis that it could have been part of a sacristy to which it would have given too low a ceiling height.[41]

The conical roof is supported by a cornice decorated with 45 modillions and 45 metopes, some original, some restored in the 19th century, others more recent (second half of 2010). The metopes and modillions, all different in style and rather naive in sculpture, represent geometric motifs (checkerboard, etc.), ornaments in the form of objects (millstone, cross, etc.), animals (fish, etc.), plants (flower, four-leaf clover, etc.) or figures (human or animal masks, etc.).[48]

Inside, the chapel is vaulted with a hemispherical dome composed of concentric courses in successive recesses.[45] All masonry, inside and out, is built of regular tufa blocks,[34] with a few courses of harder limestone at ground level.[49]; the walls are just over a meter thick[44]

In his 2011 study of the chapel, Christophe Meunier considers the dimensions chosen for the building to be symbolic. The rotunda measures 7.2 m in internal diameter, 6 m high at cornice level, and the nave 4.2 m in internal width; by transposing these dimensions into cubits, a unit commonly used in the Middle Ages but highly variable locally, these dimensions become twelve cubits for the rotunda, like the Twelve Apostles of Jesus, and seven cubits for the nave, like the seven days needed by God to create the world.[50] Meunier even considers a more direct symbolism with the Apocalypse, which mentions the seven angels and twelve gates of the heavenly Jerusalem.[51] According to the same author, the ratios between width and height of the chapel's components - rotunda, nave and roof - are applications of the principle of the golden ratio.[52] However, Bosseboeuf and, after him, Favreau,[53] give the nave a length of 8 m, while Meunier suggests a nave built on a square plan.[54]

The chapel appears to have been built on a model inspired by the Holy Sepulchre in Jerusalem and brought back from the First Crusade. Other churches, also dating from the 11th century, such as Saint-Étienne de Neuvy-Saint-Sépulchre, also follow the same general layout.[55]

Frescos[edit]

The interior of the chapel - traces of which are also to be found in the remains of the arch that marked the start of the nave[23] - was entirely decorated with polychrome Romanesque frescos painted when the building was first constructed or shortly afterwards.[56][57] Most of these frescos were already in a poor state of repair when, in 1862, the French government undertook restoration and consolidation work on the interior of the chapel, on the wall beneath the bays and on the dome, permanently erasing all traces of some of the frescos. However, in 1850, the artist Savinien Petit completed a survey of the frescos, and his work is now preserved at the Médiathèque de l'architecture et du patrimoine.[58][59] Since then, the frescos have been deteriorating;[60] the development of mold, observed during a restoration campaign in 2009, is altering certain motifs and making them difficult to interpret.[61]

Four levels, or registers, can be distinguished, from bottom to top.[62] The unity of style in the various frescos suggests to Albert Philippon that they are all the work of a single artist.[3] The style is reminiscent of the murals in Saint-Paul church in Souday[63] and Saint-Julien church in Poncé-sur-le-Loir.[64] Angelico Surchamp believes that the crypt of the collegiate church of Saint-Aignan bears frescos by the same hand as that of Le Liget.[65]

First register[edit]

From the floor to the base of the bays, the wall was covered by a "drapery with folds traced in brown"; the motif is common in Romanesque paintings.[26] It has completely disappeared,[66] although traces of paint were still visible in some masonry joints in the early 1930s.[67]

Second register[edit]

In the 21st century, the best-preserved frescos are to be found in this register.

Six large biblical scenes are interspersed between the bays. Clockwise, from the entrance to the rotunda, we find the Nativity, the Presentation of Jesus in the Temple (this iconographic theme was little used in the Romanesque period, with only three representations in France, including the one at Le Liget),[68] the Descent from the Cross, the Holy Sepulchre and the Dormition of Mary.[69] The Tree of Jesse is the sixth painting. The Descent from the Cross and the Holy Sepulchre interrupt the cycle of scenes dedicated to Mary, although she is present as a secondary figure in the Descent from the Cross.[70] Traces of paint on the intrados of the arch marking the start of the nave suggest that other scenes took place here, perhaps the Annunciation and the Visitation, which would be chronologically the first in the cycle, but this hypothesis cannot be verified.[71][72]

The embrasures of the seven windows, numbered 1 to 7 clockwise from the rotunda's main entrance, are also decorated, with fourteen full-length representations of saints, two per window. However, unlike the interspersed biblical scenes, they are arranged in a descending "hierarchical" order, starting from the bay opposite the west door, considered "axial".[42] This bay (4) features two of the apostles, Peter and Paul for most authors, except Angelico Surchamp, who replaces Paul with John the Baptist.[73] This is followed by two bays dedicated to the holy bishops (3 and 5). The next two bays are certainly occupied by abbot saints (2 and 6), the frescos in bay no. 2 having been erased; according to Christophe Meunier, Martin, then depicted as abbot and not bishop, could be one of the two figures.[74] Finally, there are four depictions of martyred[75] saints closest to the main door (1 and 7). While historians who have studied these frescos agree on the theme of each window, their interpretations of the figures differ, especially where the frescos are most damaged and the names of the saints, which originally appeared near the frescos, have been partially or totally erased. A manuscript from the Carthusian monastery, preserved in the Tours municipal library but lost in the fire of June 1940, mentions that the abbey possessed relics of most of the saints depicted in the chapel.[42] Raymond Oursel notes that none of the saints usually honored by the Carthusian monks are represented in the chapel, but that Benedict and Gilles, important figures for the Benedictines,[76] are, and Willibrord Witters makes the same observation.[16]

| Numbering

bays |

Philippon (1934)[77] | Thibout (1949)[78] | Surchamp (1965)[73] | Favreau (1988)[42] | Meunier (2011)[75] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Maurice and Vincent | Maurice | Maurice | Maurice and Eustache | Maurice and Eustache |

| 2 | - | - | - | - | Martin |

| 3 | Brice and Bénigne | Brice and Denis | Brice and Denis | Brice and Denis | Brice and Denis |

| 4 | Pierre and Paul | Pierre and Paul | Pierre and Jhon the Baptist | Pierre and Paul | Pierre and Paul |

| 5 | Nicolas and Hilary | Nicolas and Hilary | Nicolas and Hilary | Nicolas and Hilary | Nicolas and Hilary |

| 6 | Robert et Benedict | Giles and Benedict | Giles and Benedict | Giles and Benedict | Giles and Benedict |

| 7 | Stephen and Lawrance | Stephen and Lawrance | Stephen and Lawrance | Stephen and Lawrance | Stephen and Lawrance |

A representation of Christ the Pantocrator can be seen on the tympanum of the doorway between the n° 5 and 6 bays to the south.[79]

Third register[edit]

Consisting of a circular frieze above the bays, this register is rather poorly preserved. The frieze forms twenty-four niches, probably intended to house representations of the twenty-four elders of the Apocalypse. The figures of Abraham - at whose right Isaiah would have Isaiah - Ananias and Hosea can be reconstructed.[80] Most of the figures hold phylacteries in their hands, but mistakes may have been made by the painter in charge of reproducing them: the text on some phylacteries does not seem to relate to the figures holding them, suggesting possible inversions if the decorator had copied a text whose meaning he did not understand.[81]

This frieze completes the biblical scenes in the second register, but also provides a transition to the Apocalypse theme in the fourth register.[82]

Fourth register[edit]

On the intrados of the dome was a figuration of the Apocalypse, mentioned in 1625 by a Carthusian monk, in continuity with the theme of the third register.[83] This fresco was probably already too badly damaged by the poor condition of its support to be saved during the 19th century consolidations.[84] Only the names of two cities in Asia Minor, Laodicea and Philadelphia - out of the seven mentioned in the first chapters of this book - remain discernible.[85] According to Angelico Surchamp, the theme of the Agnus Dei could have appeared at the top of the dome.[65]

Architectural and epigraphic studies[edit]

The following list is not exhaustive. It is limited to those studies devoted to the chapel that have been the subject of substantial publications, and briefly summarizes their content or particularities.

In 1862, Earl Louis de Galembert wrote a memoir on the history and progress of mural painting and sculpture in Touraine from the 10th century to the early years of the 13th century (1120), published in the proceedings of the Congrès archéologique de France session held in Saumur in 1862. In this first document, very partially devoted to the chapel, he proposes an initial dating of the frescos, but does not describe them in detail.[86]

The 1948 session of the Congrès archéologique de France held in Tours was devoted to the study of monuments in Touraine. The proceedings published the following year included a chapter on the Saint-Jean du Liget chapel and its murals, architecture and frescos, written by art historian Marc Thibout.[87]

In 1965, Benedictine medievalist Angelico Surchamp published several articles on the chapel in the collective work Val de Loire roman et Touraine romane. In one of these articles, unlike his colleagues, he sees the representation of John the Baptist and not Paul in one of the chapel's figurations of saints.[73]

Voichita Muntenau's 1976 doctoral dissertation at Columbia University, published in 1978 and referred to in numerous subsequent books and articles, is entirely devoted to the study of the chapel's frescos, including proposals on dating, thematics and precise description of the motifs.[88]

Historian Robert Favreau conducted a study on the painting and epigraphy of the Liget chapel. The text was published under several titles in various collections and journals, including Cahiers de l'inventaire in 1988. While the publication is largely devoted to the description and interpretation of the frescos, it also touches on other aspects of the monument, such as its controversial dedication to Saint John.[89]

Written in 2011, this is the first book to be devoted in its entirety to the chapel, which is studied from historical, architectural and epigraphic angles. Its author, Christophe Meunier, takes stock of the knowledge acquired and the questions still unanswered, and develops the original hypothesis of a construction whose dimensions are an application of the golden ratio.[90]

As part of a doctoral thesis in art history to be defended in 2021, Amaelle Marzais is studying the chapel's frescos from both stylistic and technical points of view, along with the painted decorations of other religious buildings in the Indre-et-Loire region.[91]

References[edit]

- ^ Dufaÿ, Bruno (2014). "La Corroirie de la Chartreuse du Liget à Chemillé-sur-Indrois (Indre-et-Loire). Étude historique et architecturale". Revue archéologique du centre de la France (53): 14–16.

- ^ a b Philippon (1934, p. 326)

- ^ a b Philippon (1934, p. 332)

- ^ "Géoportail". www.geoportail.gouv.fr. Retrieved 2024-02-08.

- ^ a b Brequigny, Louis-George Oudart-Feudrix (1783). Table chronologique des diplomes, chartes, titres et actes imprimes concernant l'histoire de France continuee par M. Pardessus (in Latin). L'impr. royale.

- ^ "LIGE : Définition de LIGE". www.cnrtl.fr. Retrieved 2024-02-08.

- ^ Favreau (1988, p. 41)

- ^ a b Favreau (1988, p. 47)

- ^ Dufaÿ, Bruno (2014). "La Corroirie de la Chartreuse du Liget à Chemillé-sur-Indrois (Indre-et-Loire). Étude historique et architecturale". Revue archéologique du centre de la France (53): 11 and 14.

- ^ Dufaÿ, Bruno (2014). "La Corroirie de la Chartreuse du Liget à Chemillé-sur-Indrois (Indre-et-Loire). Étude historique et architecturale". Revue archéologique du centre de la France (53): 10.

- ^ Oursel (1980, pp. 297 and 302)

- ^ Meunier (2011, p. 65)

- ^ Witters (1965, p. 210)

- ^ texte, Société archéologique de Touraine Auteur du (1959). "Bulletin de la Société archéologique de Touraine". Gallica. Retrieved 2024-02-08.

- ^ Lorans, Élisabeth (1996). Le Lochois du Haut Moyen Âge au xiiie siècle - territoires, habitats et paysages. Tours: Publication de l'Université de Tours. p. 130. ISBN 2-86906-092-0.

- ^ a b c Witters (1965, p. 216)

- ^ Meunier (2007, pp. 18–20)

- ^ Meunier (2007, p. 35.)

- ^ Meunier (2011, pp. 65-68.)

- ^ Terrier-Fourmy, Bérénice (2002). Voir et croire. Peintures murales médiévales en Touraine. Tours: Conseil général d'Indre-et-Loire. p. 94.

- ^ Thibout (1949, p. 176)

- ^ Bossebœuf (1897, p. 18)

- ^ a b Meunier (2007, p. 37)

- ^ Munteanu (1978, p. 163)

- ^ Meunier (2011, p. 68)

- ^ a b Thibout (1949, p. 180)

- ^ Witters (1965, p. 214)

- ^ Dufaÿ, Bruno (2014). "La Corroirie de la Chartreuse du Liget à Chemillé-sur-Indrois (Indre-et-Loire). Étude historique et architecturale". Revue archéologique du centre de la France (53): 17.

- ^ Thibout (1949, p. 179)

- ^ a b c Philippon (1934, p. 327)

- ^ Thibout (1949, pp. 178–179)

- ^ "Chapelle Saint-Jean-du-Liget". Plateforme ouverte du patrimoine.

- ^ a b Thibout (1949, pp. 177–178)

- ^ a b Meunier (2011, p. 8)

- ^ Thibout (1949, p. 177)

- ^ Meunier (2011, pp. 7-9.)

- ^ "La Nouvelle République du Centre-Ouest". Sennevières : le maire fait le bilan de 13 années. 2014.

- ^ Marzais (2021, p. 671)

- ^ "Fiche Détail". www.atelier-arcoa.com. Retrieved 2024-02-08.

- ^ Bossebœuf (1897, p. 13)

- ^ a b Thibout (1949, p. 175)

- ^ a b c d Favreau (1988, p. 46)

- ^ Surchamp (1965, p. 195)

- ^ a b Surchamp (1965, p. 224)

- ^ a b Philippon (1934, p. 328)

- ^ Bossebœuf (1897, p. 12)

- ^ Ranjard, Robert (1958). La Touraine archéologique : guide du touriste en Indre-et-Loire (3rd ed.). Mayenne: Imprimerie de la Manutention. pp. 278–279. ISBN 2-855-54017-8.

- ^ Meunier (2011, pp. 23–27)

- ^ Thibout (1949, p. 174)

- ^ Meunier (2011, pp. 19–20)

- ^ Meunier (2011, p. 21)

- ^ Meunier (2011, pp. 21–22)

- ^ Favreau (1995, p. 140)

- ^ Meunier (2011, p. 20)

- ^ Meunier (2011, pp. 11–17)

- ^ Couderc, Jean-Mary (1987). Dictionnaire des communes de Touraine. Chambray-lès-Tours: C.L.D. p. 496. ISBN 2-85443-136-7.

- ^ Granboulan, Anne (1989). "Peintures murales romanes. Méobecq, Saint-Jacques-des-Guérets, Vendôme, Le Liget, Vicq, Thevet-Saint-Martin, Sainte- Lizaigne, Plaincourault (Cahiers de l'Inventaire, 15). Inventaire général, région Centre-CESCM, 1988, 111 p." Bulletin Monumental. 147 (4): 364–365.

- ^ Meunier (2011, p. 31)

- ^ "Annales archéologiques / dirigées par Didron aîné,..." Gallica. 1855. Retrieved 2024-02-09.

- ^ Favreau (1988, p. 42)

- ^ Reille-Taillefert, Geneviève (2010-01-21). Conservation-restauration des peintures murales: De l'Antiquité à nos jours (in French). Editions Eyrolles. ISBN 978-2-212-17576-9.

- ^ Meunier (2011, pp. 33–34)

- ^ Thibout (1949, p. 192)

- ^ texte, Société historique et archéologique du Maine Auteur du (1892). "Revue historique et archéologique du Maine". Gallica. Retrieved 2024-02-09.

- ^ a b Surchamp (1965, p. 206)

- ^ Gelis-Didot, Pierre; Laffillée, Henri (1896). La peinture décorative en France du xie au xvie siècle (2nd ed.). Paris: Librairies-Imprimeries Réunis.

- ^ Philippon (1934, p. 329)

- ^ Ferraro, Séverine (2012). Les images de la vie terrestre de la Vierge dans l'art mural (peintures et mosaïques) en France et en Italie. Dijon: Université de Bourgogne. p. 52.

- ^ Meunier (2011, pp. 35–46)

- ^ Favreau (1988, p. 44)

- ^ Thibout (1949, pp. 181–183)

- ^ Favreau (1988, p. 43)

- ^ a b c Surchamp (1965, pp. 205–206)

- ^ Meunier (2011, p. 55)

- ^ a b Meunier (2011, pp. 50–62)

- ^ Oursel (1980, p. 305.)

- ^ Philippon (1934, pp. 329–330)

- ^ Thibout (1949, pp. 189–191)

- ^ Meunier (2011, pp. 63–64)

- ^ Meunier (2011, pp. 47–49)

- ^ Favreau (1988, p. 45)

- ^ Meunier (2011, p. 47)

- ^ Thibout (1949, p. 191)

- ^ Surchamp (1965, p. 219)

- ^ Meunier (2011, p. 34)

- ^ de Galembert (1862, p. 167)

- ^ Thibout (1949)

- ^ Munteanu 1978.

- ^ Favreau (1988)

- ^ Meunier 2011.

- ^ Marzais 2021.

Bibliography[edit]

- Favreau, Robert (1988). "Peinture et épigraphie : la chapelle du Liget". Cahiers de l'inventaire (15). Éditions du patrimoine: 41–49.

- Meunier, Christophe (2011). La chapelle Saint-Jean du Liget. Chemillé-sur-Indrois: Hugues de Chivré. p. 78. ISBN 978-2-91604-346-3.

- Munteanu, Voichita (1978). The cycle of frescoes of the Chapel of Le Liget. New York: Garland Pub. p. 269. ISBN 0-82403-244-6.

- Oursel, Raymond (1980). "Histoire du Liget". Révélation de la peinture romane. Saint-Léger-Vauban: Zodiaque: 295–306.

- Terrier-Fourmy, Bérénice (2002). Voir et croire. Peintures murales médiévales en Touraine. Tours: Conseil général d'Indre-et-Loire. p. 126. ISBN 2-85443-412-9.

- Thibout, Marc (1949). "La chapelle Saint-Jean du Liget et ses peintures murales". Congrès archéologique de France. CVIe session tenue à Tours en 1948, Paris: Société française d'archéologie. pp. 173–194.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location (link) - Desfarges, Bénigne; et al. (1965). Val de Loire roman et Touraine romane. Saint-Léger-Vauban: Zodiaque.

- Witters, Willibrord. "Notes historiques sur les fresques du Liget". In Desfarges (1965).

- Surchamp, Angelico. "Le Liget - les fresques du Liget". In Desfarges (1965).

- Bossebœuf, Louis-Auguste (1897). "De l'Indre à l'Indrois : Montrésor, le château, la collégiale, et ses environs : Beaulieu-Lès-Loches, Saint-Jean le Liget et la Corroirie". Monographie des villes et villages de France. Res Universis. p. 103. ISBN 2-74280-097-2.

- Favreau, Robert (1995). Études d'épigraphie médiévale. Vol. 1995. Limoges: Presses universitaires de Limoges. p. 621.

- Focillon, Henri (1938). Peintures romanes des églises de France. Paris: Hartmann.

- de Galembert, Louis (1862). "Mémoire sur l'histoire et les progrès de la peinture murale et de la sculpture en Touraine depuis le xe siècle jusqu'aux premières années du xiiie siècle (1120)". Congrès archéologique de France. Paris: Société française d'archéologie. pp. 158–187.

- Marzais, Amaelle (2021). De la main à l'esprit : étude sur les techniques et les styles des peintures murales dans l'ancien diocèse de Tours (xie et xve siècles). Vol. I, II and III. Tours: Centre d'études supérieures de le Renaissance. pp. 319, 268 and 915.

- Meunier, Christophe (2007). La chartreuse du Liget. Chemillé-sur-Indrois: Hugues de Chivré. p. 172. ISBN 978-2-91604-315-9.

- Philippon, Albert (1934). "La chartreuse du Liget (suite)". Bulletin de la Société archéologique de Touraine (XXV): 289–342. ISSN 1153-2521.