James Tochatti

James Tochatti | |

|---|---|

James Tochatti in 1896 | |

| Born | 1852 Ballater, Aberdeenshire, Scotland |

| Died | (aged 75) |

| Occupations |

|

| Movement | |

| Spouse |

Louisa Susan Kaufmann

(m. 1877; died 1927) |

| Children | 3 |

| Signature | |

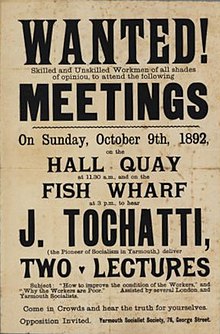

James Tochatti (1852 – 22 November 1928), was a Scottish anarchist agitator, merchant tailor, trade unionist, newspaper editor and public speaker. From 1894 to 1896 he was editor of the monthly anarcho-communist paper Liberty.

Biography[edit]

James Tochatti was born in 1852 in Ballater, Aberdeenshire, Scotland, to police constable Joseph Tochatti and his wife Jane Cormack.[1][2][3] In the 1860s the family moved to Leeds. Tochatti began studying medicine as well as working as a stationer before becoming a merchant tailor. In the mid-1870s he moved to London and became active in the National Secular Society.[4][3] At this time he also began practising and lecturing on the pseudosciences phrenology and physiognomy.[3] In 1877 he married Louisa Susan Kaufmann with whom he went on to have three children.[5][3] In 1882 Tochatti was charged with disorderly conduct outside a cheesemongers in Hammersmith in a dispute over closing times.[6]

Tochatti was active in the Hammersmith Radical Club, and in 1885 he was a founding member of the Hammersmith branch of the Socialist League.[3] In 1886 he was elected to the Socialist League's Hammersmith branch.[2] His wife, Louisa, was also active in the branch.[3] He regularly undertook public speaking and contributed to the League's paper Commonweal.[4][3] At this time he also began to align with anarchist communism. Tochatti served as the branch president of the National Labour Federation trade union during the successful 1889 strike over low pay at the John Isaac Thornycraft shipyard in Chiswick.[3]

In 1890 the Socialist League split, with the Hammersmith branch leaving the League to become the Hammersmith Socialist Society. Tochatti remained a member of the League and of the Hammersmith society despite the society adopting an anti-anarchist stance.[7][3] Tochatti remained a friend of William Morris despite the split.

In the 1890s he served as organising secretary of the United Shop Assistants' Union. He was arrested in 1890 during a protest and again in 1891 when he was fined for disorderly behaviour at a picket by the union outside a shop in Marylebone in a dispute over closing times.[3][4][8] On May Day 1894 Tochatti was attacked while speaking on anarchism.[3]

In January 1894 Tochatti founded the anarchist monthly newspaper Liberty: A Journal of Anarchist Communism.[9] The paper was avowedly against political violence and "bombastic talk", arguing that it only served to alienate people from the anarchist cause.[7] The paper was produced in the book-lined basement of Tochatti's shop on Beadon Road in Hammersmith. Though the paper was explicitly anarcho-communist it facilitated conversation between anarchists and anti-parliamentary socialists following the split of the Socialist League.[7] In December 1896 he announced that he was suspending publication of the paper due to ill health, though finances were likely also a contributing factor.[2][7]

Tochatti continued to lecture in the 1900s and 1910s.[3] He died in Poole, Dorset on the 22 November 1928 aged 75.[10][11]

References[edit]

- ^ Couzin, John (2012). Radical Glasgow: A Skeletal Sketch of Glasgow's Radical Tradition. Internet Archive. Glasgow: Voline Press. p. 34. ISBN 978-0-9537394-5-5.

- ^ a b c Oliver, Hermia (1983). The International Anarchist Movement in Late Victorian London. London: Croom Helm. pp. 60–61, 125–126. ISBN 0-312-41958-9. OCLC 9282798.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Williams, Stephen; Boos, Florence (Winter 2017). "James Tochatti: A Little-Known Morris Socialist Comrade" (PDF). Useful and Beautiful. 2017 (2): 25–28. Archived (PDF) from the original on 23 March 2022. Retrieved 16 October 2022.

- ^ a b c Heath, Nick (22 January 2007). "Tochatti, James, 1852-1928". libcom.org. Archived from the original on 14 October 2022. Retrieved 15 October 2022.

- ^ "Index entry". FreeBMD. ONS. Archived from the original on 16 October 2022. Retrieved 15 October 2022.

- ^ "THE EARLY CLOSING MOVEMENT". Lloyd's Weekly Newspaper. 8 October 1882. p. 3. Archived from the original on 16 October 2022. Retrieved 15 October 2022.

- ^ a b c d Quail, John (2019). The Slow Burning Fuse: The Lost History of the British Anarchists. Constance Bantman, Nick Heath. Internet Archive. Oakland and London: PM Press and Freedom Press. pp. 177, 229, 380. ISBN 978-1-62963-633-7. OCLC 1089126285.

- ^ "BOYCOTTING A TRADESMAN". Morning Post. 17 October 1891. p. 2. Archived from the original on 16 October 2022. Retrieved 15 October 2022.

- ^ W.M. (February 1927). "A Fighter of Forlorn Hopes". Freedom. p. 8.

- ^ Nettlau, Max (1996). A Short History of Anarchism. Internet Archive. London: Freedom Press. p. 403. ISBN 0-900384-89-1. OCLC 37529250.

- ^ "Index entry". FreeBMD. ONS. Archived from the original on 16 October 2022. Retrieved 15 October 2022.