The twin relics of barbarism

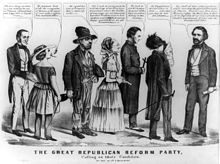

The twin relics of barbarism refer to the popular nineteenth-century phrase that linked the practices of slavery and polygamy in the United States. Attention to these twin relics increased following the 1856 Republican National Convention as the party acknowledged both practices in their party platform. Within the party's planks, they called on Congress to firmly denounce the "twin relics of barbarism –– Polygamy and Slavery."[1] During this period, slavery was widely practiced among southern states, and polygamy was becoming prevalent among members of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (popularly referred to as Mormons). The growth of these practices stoked fear and uncertainty in the nation at large as the two practices were seen as "incongruous with the pure and the free, the just and safe principles inaugurated by the [American] Revolution."[2] As a result of the widespread opposition to each, they were increasingly coupled together in national print media throughout the country.

Following the Civil War, slavery was abolished and equality for African-Americans began with the passage of the Thirteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution, the Fourteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution, and the Fifteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution. Polygamy was eventually outlawed in the 1880s following the passage of numerous pieces of anti-polygamy legislation including the Morrill Anti-Bigamy Act of 1862, the Edmunds Act of 1882, and the Edmunds–Tucker Act of 1887 as well as the landmark Supreme Court case Reynolds v. United States.

1856 Republican National Convention[edit]

The first Republican National Convention[edit]

The 1856 Republican National Convention was held from June 17 to 19, in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, with the aim to nominate a Republican candidate for president in the upcoming election. Only two years prior, the Republican Party had been formed to fight the expansion of slavery, specifically, in the western territories. This convention was prefaced by an informal convention in February of the same year, to establish the national organization and properly delegated officials in preparation for the official conventions four months later.

Opposition to slavery[edit]

The opposition to slavery began during the Age of Enlightenment, which ideas of the value of human happiness, the pursuit of knowledge, and liberty. The first statement against slavery in Colonial america was drafted by Francis Daniel Pastorius who was a leader in a Quaker Church. In the United States, the southern slavocracy was an expression also known as the southern way of life. This form of economy was powerful enough to force the North to allow the South to join The Union with slavery. The South's military power and economic well-being were sufficient and necessary for The Union to become bigger and stronger, although slavery was opposed by almost all of the northern states.

Opposition to polygamy[edit]

Polygamy came into the limelight in The United States because of the practices of members of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (LDS Church). While plural marriage had been practiced for years prior, the first public acknowledgment of plural marriage among Saints came in 1852.[3] One of the major questions concerning polygamy in the 1856 Republican National Convention was to know if Congress had the power to prohibit the "domestic institution" of plural marriage. If Congress did possess this authority, how was it to be checked?[3] Negative attention was quickly spread among the Latter-day Saint community as a result of this practice. Likewise, when the "Mormon Question", polygamy, first appeared in national news, there was consistent denial of the practice of polygamy by Mormon publicists.[3] Years later, in 1862, an anti-polygamy act was intended to "punish and prevent the Practice of Polygamy."[4]

Linking the twin relics[edit]

Initial connection[edit]

Prior to the overt connection between the practices of polygamy and slavery at the 1856 Republican National Convention, the link was not very widespread. However, two months prior to the convention the Chicago Daily Tribune published a circular linking the two practices as it compared the women participating in polygamy to slaves.[2] During the National Convention, Representative John A. Wills of California, a long-time abolitionist, was the first to speak at the podium. Wills would be the one to contribute the impactful statement aligning slavery and polygamy as "twin relics."[5] Later in his life, Wills wrote a letter to the Historical Society of Southern California, Los Angeles reflecting on his contribution to the convention stating, "the duty of drafting the resolutions...against slavery in the territories of the United States, was assigned to me...No special instruction was given to me on the subject of polygamy in the territories. But as polygamy was already odious in the public mind and a growing evil...in order to...strengthen the case against slavery...I determined to couple them together in one and the same resolution."[6]

Effects of the media[edit]

Following the Republican National Convention, the comparison slowly became more prevalent in media throughout the states and territories. Prior to the outbreak of the Civil War, a note to the editor in the New York Times further denounced the two practices as it stated, "Slavery and Polygamy have many points of sympathy...If because polygamy is immoral and degrading, what is to be said of Slavery?...the Republican Platform of 1856, when it spoke of Slavery and Polygamy as 'twin relics of barbarism,' did not utter a mere rhetorical flourish, but enunciated a profound political truth."[7] This same letter argued that polygamy likely could have been quelled within a few months; however, the South would not have supported the precedent that this would have held as it would have had a direct effect on the practice of slavery.[7]

As the threat of a civil war loomed on the horizon, the twin relics became entrenched in politics in the North as many began to fear polygamy would become a new form of slavery in the United States. Naturally, abolitionists supported the anti-polygamy movement as the label of "twin relics" implied a clear similarity and relationship between the two practices.[8]

Aside from coverage in news media, abolitionists and anti-polygamists brought attention to slavery and polygamy through the publication of novels and stories.[9] In the same fashion that Harriet Beecher Stowe's novel Uncle Tom's Cabin influenced the nation's thoughts on slavery, many books were published on the topic of polygamy with hopes of a similar effect.[9]

As the practices became further intertwined in the media, so did the locations in which they resided –– Charlestown, South Carolina, and Salt Lake City in the Utah Territory. An article in the Chicago Press and Tribune remarked, "the two systems –– that of Utah and that of South Carolina –– have so many points of resemblance...that they will make common cause in self-defense."[10] Historian Kenneth Alford observed that articles and news stories condemning slavery and polygamy soon became so similarly worded that they were almost indistinguishable from one another.[11] During this period, the Utah Territory sought statehood, causing many to be wary of the potential growth of polygamy. This was addressed in the Daily [Richmond] Dispatch which stated, "The Mormons have organized their State Government with polygamy as the 'corner stone' of their system, just as slavery is the corner stone of the Confederates."[12] These parallels continued to be drawn by many news outlets, Union and Confederate alike.

Refuting the connection[edit]

Not all agreed with the linkage of slavery and polygamy. Many Southerns wished to distance the practice of slavery from polygamy as they did not want the national ire directed at polygamy to be added to slavery. Senator Stephen A. Douglas of Illinois attempted to separate the two relics by publicly defending slavery and decrying polygamy. An excerpt of one of his speeches was printed in the Valley Tan and stated, "Admitting even for the sake of argument that slavery is an evil; for slavery existed in every state in the union but one, at the time of the formation and adoption of the constitution…. The constitution was framed recognizing its existence and protecting the rights which grew up under it; if a wrong, therefore slavery was a mutual and general wrong… not so with polygamy…. Polygamy exists without authority, and is practised [sic] in violation of the moral sentiments of the entire nation with the exception of a few thousand people."[13] Likewise, other Southern Democrats viewed polygamy to be the destruction of marriage and did not wish to be associated with the practice.

The downfall of the twin relics[edit]

Legislation to end slavery[edit]

The downfall of slavery began with the Abolitionist movement and the Republican Party establishing a strategy of ending slavery in the United States. This strategy involved the United States Constitution, using its clauses to abolish slave trades and slavery as a whole. Congress decided that preventing the admission of new slave states would be the first step in abolishment, next they use the Commerce Clause to ban interstate slave trade preventing the migration of slaves to the southwest.[14] John Alexander Wills began an uproar concerning the morality and legality of slavery that helped kickstart the Republican Party in California to start its siege against slavery. Due to the Kansas-Nebraska Act of 1854, there was an immediate possibility of danger for the anti-slavery rhetoric which could have awoken the majority of politicians in the North to express power of the slaveholders that had their place in Washington D.C.[5]

In 1865 the 13th Amendment to the U.S Constitution was passed and states "all persons held as slaves within any State, or designated part of a State... shall be then, thenceforward, and forever free."[15] This amendment worked in tandem with the 14th and 15th amendments. The 14th amendment enforced citizenship and the State cannot deprive any person of life, liberty, or property. The 15th amendment gave the newly freed slaves the right to vote.[16] These three amendments all worked together to make the newly freed slaves official citizens of The United States.

Legislation to end polygamy[edit]

The first act of anti-polygamy legislation, the Morrill Anti-Bigamy Act, was passed by Congress in 1862. The act was named after Republican Senator Justin Smith Morrill who was known for his staunch opposition to the practice of both slavery and polygamy.[17] This act prohibited the marriage of a man to more than one woman in all territories of the United States. However, the act was largely a failure, proving unenforceable as juries within the Utah Territory were controlled by Mormons.[17]

In 1879, the Supreme Court ruled in the landmark case of Reynolds v. United States that religious liberty was not a sufficient defense to a criminal indictment, and that polygamy was not protected by the First Amendment.[18] The next major act against polygamy, the Edmunds Act, came in 1882 and defined "unlawful cohabitation" as a federal crime, and removed the rights of suffrage and participation on juries from Mormons.[18] Five years later, Congress passed the Edmunds-Tucker Act which effectively outlawed polygamy. This statute established federal crimes of adultery, fornication, and incest for men and women found to be practicing polygamy.[18] The LDS Church itself banned polygamy in the 1890 Manifesto, though some dissident Mormon fundamentalists continue the practice illegally.

References[edit]

- ^ "Republican Party Platform of 1856 | The American Presidency Project". www.presidency.ucsb.edu. Retrieved November 18, 2022.

- ^ a b ""Republican Presidential Convention. Circular of the National Committee Appointed at Pittsburgh on 22d February. 1856,"". Chicago Daily Tribune. April 15, 1856. p. 2.

- ^ a b c "The Mormon Question Enters National Politics, 1850–1856". issuu. Retrieved November 28, 2022.

- ^ Rothera, Evan C. (March 2016). "The Tenacious "Twin Relic": Republicans, Polygamy, and The Late Corporation of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints v. United States: POLYGAMY AND SLAVERY". Journal of Supreme Court History. 41 (1): 21–38. doi:10.1111/jsch.12091. S2CID 148549941.

- ^ a b Karp, Matthew (December 2019). "The People's Revolution of 1856: Antislavery Populism, National Politics, and the Emergence of the Republican Party". Journal of the Civil War Era. 9 (4): 524–545. doi:10.1353/cwe.2019.0072. S2CID 208811515 – via JSTOR.

- ^ Wills, John A. (March 27, 1890). "The Twin Relics of Barbarism". Historical Society of Southern California, Los Angeles. 1 (5): 41 – via JSTOR.

- ^ a b "American Politics in Europe". New York Times. November 28, 1859. p. 2.

- ^ Barringer Gordon, Sarah (2002). The Mormon Question: Polygamy and Constitutional Conflict in Nineteenth-Century America. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press. pp. 55–57. ISBN 978-0-8078-4987-3.

- ^ a b Alford, Kenneth (May 2017). "South Carolina and Utah—Conjoined as the Nineteenth Century's 'Twin Relics of Barbarism". Proceedings of the South Carolina Historical Association: 9.

- ^ "Twin Relics of Barbarism". Chicago Press and Tribune. March 28, 1860. p. 2.

- ^ Alford, Kenneth (May 2017). "South Carolina and Utah—Conjoined as the Nineteenth Century's 'Twin Relics of Barbarism". Proceedings of the South Carolina Historical Association: 10.

- ^ "The New Mormon Complication". Daily [Richmond] Dispatch. May 28, 1862. p. 4.

- ^ "The Speech of Senator Douglas and the Doctrine of Popular Sovereignty in the Territories". Valley Tan. September 11, 1859. p. 2.

- ^ Oakes, James (2021). The Crooked Path to Abolition: Abraham Lincoln and the Antislavery Constitution. (W.W. Norton).

- ^ "13th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution: Abolition of Slavery (1865)". National Archives. September 1, 2021. Retrieved November 28, 2022.

- ^ "15th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution: Voting Rights (1870)". National Archives. September 7, 2021. Retrieved November 29, 2022.

- ^ a b Barringer Gordon, Sarah (2003). "The Mormon Question: Polygamy and Constitutional Conflict in Nineteenth-Century America". Journal of Supreme Court History. 28 (1): 23.

- ^ a b c Kincaid, John (2003). "Extinguishing the Twin Relics of Barbaric Multiculturalism-Slavery and Polygamy: From American Federalism". Publius. 33 (1): 85. doi:10.1093/oxfordjournals.pubjof.a004979 – via JSTOR.