Legendary horses of Pas-de-Calais

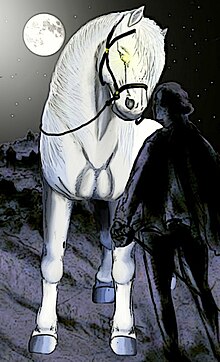

The legendary horses of Pas-de-Calais are fabulous, diabolical white animals, mentioned in the folklore of Artois, Ternoise and Boulonnais under various names. The blanque mare is said to appear at dusk or in the middle of the night to deceive children and men. She would tempt the latter to ride her, and her back could stretch to accommodate, usually, up to seven riders. Once they had settled on her back, she would lure them into traps or throw them into the water. This animal is also mentioned under the same name in Samer.

Ech goblin and the qu'vau blanc from Saint-Pol-sur-Ternoise, which wore a collar with bells to attract its victims, play the same role, as does ch'blanc qu'vo from Maisnil, or the animal from Vaudricourt, a white horse or gray donkey that carried off twenty children and eventually drowned them. All these legends from the region are part of French folklore, with its abundance of pale, evil horses associated with night, water and their dangers.

Etymology and terminology[edit]

The names blanque jument (white mare), qu'vau blanc (white horse), ech goblin (the goblin) and ch'blanc qu'vo (the white horse) are all mentioned in the Pas-de-Calais department, generally around the 19th century in their original Picard language.[citation needed]

Legends[edit]

The Nord-Pas-de-Calais region abounds in legends, whether attached to trees, stones, mountains, ghosts, the devil, giants, saints or fantastic animals. According to Bernard Coussée, "there isn't a city, a village or a market town that doesn't have a bit of an enigma to tell".[1] Among fantastic animals, the horse is mentioned several times in the Pas-de-Calais department. These legends share many common features in the vision of these pale horses, with their negative symbolism, their lengthening backs and all ending up rid of their riders, usually by throwing them into the water.

Blanque mare from Boulonnais and Samer[edit]

According to Bernard Coussée and the Société de Mythologie Française, the blanque mare appears on full-moon nights in the Boulonnais region. Its back can stretch to allow seven riders to sit on it, but the fabulous animal always ends up getting rid of it in the water. This legend is also common in Artois, particularly in the Ternoise region.[2][3]

The Boulonnais horse is a breed of draft horse unique to the region, with a light gray coat that is often perceived as white.[4] No link has been established between this breed of horse and legends featuring white horses.[citation needed]

The blanque mare was mentioned in detail in a letter from a doctor, M. Vaidy, to M. Eloi Johanneau on 4 June 1805 in Samer. It is recorded by the Celtic Academy:

"Finally, my dear friend, I went to visit the Tombelles, guided by a peasant woman who told me, without my asking, that this place was the cemetery of a foreign army that had occupied the area around Questreque a long time ago. This ancient burial ground is now a small piece of communal land, situated half a league south of Samer, and three-quarters of a league south-west of Questreque, on an arid plain at the foot of Mont de Blanque-Jument (...). The Mont de Blanque-Jument, according to the tradition of the inhabitants of Samer, is so named because a white mare of perfect beauty, belonging to no master, was once seen on its summit, approaching passers-by and offering her rump to be ridden. All wise people were wary of yielding to such a seduction. But one day, an unbeliever had the temerity to ride the white mare, and was immediately struck down and crushed. Since that time, the mare, or rather the spirit that had taken that form, has never reappeared". - Dr Vaidy, Mémoires de l'Académie celtique[5]

This story is repeated in the same way by Paul Sébillot, in his unfinished work Le folklore de France,[6] and quickly mentioned by Henri Dontenville, founder of the Société de Mythologie Française.[7][8] The place known as "de Blanque jument" is located south of Samer, near Le Breuil,[2] and appears to have been mentioned by this name as early as 1504.[9]

Ech Goblin, qu'vau blanc or ch'gvo blanc from Saint-Pol-sur-Ternoise[edit]

Ech goblin, also known as qu'vau blanc[3][10] or ch'gvo blanc,[11] is a creature similar to the blanque mare,[2] which was recorded in the nineteenth century as a type of lutin, specifically a goblin capable of assuming the form of a mammal with long white fur and a collar of bells around its neck. The melodious sound of these bells encourages people, especially children, to ride the animal as soon as they hear it. The ech goblin's back lengthens as more and more people mount it. When it has enough on its back, it races to the nearest river to drown its riders.[10][11] At night, this creature would hide in quarries or excavations along roads leading to the forest.[3]

Up until the 1830s,[10] ech goblin was evoked to frighten disobedient children, who were told to "Gare a ti, v'lo ch'goblin", mainly in the Saint-Pol-sur-Ternoise region, near Béthune.[3][11] Ech goblin was also the name given to the local sludge-collector's cart, to which a horse or donkey with bells was hitched.[11]

Ch'blanc qu'vo de Maisnil[edit]

Ch'blanc qu'vo is mentioned by elficologist Pierre Dubois in his Encyclopédie des fées as a fabulous horse specific to Maisnil, whose mane is trimmed with bells.[12] Mlle Leroy reports in Henri Dontenville's La France mythologique that, according to a folklorist from Artesia, ch 'blanc qu'vose is confused with ech goblin "which was used to threaten unbearable children".[13]

Vaudricourt gray donkey or white horse[edit]

Two similar creatures are mentioned in Vaudricourt, one as a gray donkey and the other as a white horse.

In his Evangiles du Diable, Claude Seignolle tells of a gray donkey that appeared in the square at Vaudricourt during midnight mass and obediently allowed itself to be ridden by the children fleeing the church, stretching out its back so that twenty of them could sit on it. When the mass was over, it bolted at full speed and plunged into a trough where all its victims were drowned. Since then, the horse has reappeared every Christmas Eve carrying the damned children, circling the village, returning to its starting point at midnight and returning to the trough from which it emerged.[14]

Pierre Dubois mentions the same story in his Encyclopédie des fées, but this time it concerns a "magnificent white horse" that drowns its young riders in a bottomless pond, and disappears into a chasm after each of its reappearances on Christmas Day.[12]

Origin and symbolism[edit]

The blanque mare and its equivalents in western Pas-de-Calais have characteristics very similar to those of other fabulous horses in popular folklore, particularly in France and Germany. The Dictionnaire des symboles cites a large number of "nefarious horses, accomplices of swirling waters".[15] The exact origin of these legends is not known, but as far back as Roman times, Tacitus mentioned white horses in sacred groves, which fascinated people.[2] These fabulous horses may have originated from the memory of ritual horse sacrifices practiced by the Gauls, who usually performed them in water, as an "offering to the powers of the elements" or in honour of the Sun. Last but not least, a number of elements can be traced back to the legend of the horse Bayard, whom Charlemagne tried to drown by tying a millstone around its neck. Bayard has the peculiarity of having a spine that stretches out to carry the four Aymon brothers, just like the white mare.[2] Henri Dontenville sees Bayard as a myth derived from the sacred Germanic horse, which in turn gave rise to the blanque mare and the bian horse, but Bayard is clearly described as reddish-brown.[16]

According to Bernard Coussée, the blanque mare's elongated spine, found in many other fairy-horse legends, is a later addition, influenced by other legends, since stories about white horses drowning the unwary had been circulating in the Pas-de-Calais for a long time, and their function was to frighten children away from dangerous areas.[2] According to Henri Dontenville, this is a serpentine, or at least reptilian, characteristic. Indeed, "you only have to watch a snake, or more simply an earthworm, unwind to understand where this myth comes from".[17]

There are many other horses in French folklore with extendable rumps and backs, or a link to water, as elficologist Pierre Dubois mentions in his Encyclopédie des fées, citing the Mallet horse, Bayard (one of the few not mentioned as evil), the Guernsey horse, or the Albret horse, alongside the blanque mare. Most of these "fairy horses" end up drowning their riders after tempting them to mount them. Pierre Dubois says that "these animals are descended from Pegasus and Unicorns, and if they have become fierce, it's because mankind has failed to tame them". The story is often very similar, featuring a beautiful pale horse appearing in the middle of the night, who gently lets himself be ridden, before escaping the control of his rider(s). One way to get rid of it is to make the sign of the cross, or recite three Our Fathers.[12]

White color[edit]

The "lunar" white color of these animals is that of cursed horses. Several works, such as the Dictionary of Symbols, focus on these "pale and pallid" horses, whose symbolism is the opposite of Uranian white horses such as Pegasus. According to Jean-Paul Clébert, the whiteness of these animals is "nocturnal, lunar, cold and empty".[18] Like a shroud or a ghost, they evoke mourning, like the white mount of one of the four horsemen of the Apocalypse, which heralds death.[15] Henri Gougaud attributes the same symbolism to the white mare, "nocturnal, livid as mists, ghosts and ointments".[19] It is an inversion of the usual symbolism of the color white, a "deceptive appearance" and a "confusion of genders".[20] Many also see it as an archetype of the horses of death, the blanque mare sharing the same symbolism as the Bian cheval des Vosges or the German Schimmelreiter,[21][22] an animal of marine catastrophe that breaks dikes during storms, and of which it is a negative and sinister "close relative".[23][24] In England and Germany, encountering a white horse is a sign of bad omen or death.[22]

Nature and function[edit]

The equine creatures of the Pas-de-Calais are all more or less assimilated to the transformation of a spirit, a goblin or the Devil himself. The Celtic Academy asserts that the blanque mare of Boulonnais is the manifestation of a spirit,[5] and Claude Seignolle likens the gray donkey of Vaudricourt to a transformation of the Devil into an animal.[14] Édouard Brasey sees the blanque mare and the Schimmel Reiter as lutins or bogeymen charged with frightening disobedient children, as opposed to the Mallet horse, which is said to be a form of the Devil himself.[25] Ech Goblin is likened to a goblin, a kind of sprite who transformed himself to frighten children.[3] Ch'qu'vau blanc is the same goblin, taking the form of a white animal.[2]

A study of changelings notes that "at the water's edge, the silhouettes of the goblin and the horse tend to merge".[26] According to another study on the dwarf in the Middle Ages, there are very close links between goblins and fantasy horses (or fairy-horses), for in both folk songs and more modern folklore, when the little people adopt an animal form, it is most often that of a horse.[27] The Japanese author Yanagida sees this as a ritual transformation of the horse into the liquid element, and notes that as far back as the Neolithic period, water genies have been associated with equines.[28]

See also[edit]

References[edit]

- ^ Coussée (2006)

- ^ a b c d e f g Coussée (1994, pp. 205–207)

- ^ a b c d e Coussée (1996a, p. 61)

- ^ "Le boulonnais". boulonnais.fr (in French). Retrieved 5 December 2009.

- ^ a b Collectif (1810, p. 108)

- ^ Sébillot (1907, p. 42)

- ^ Dontenville (1973a, p. 144)

- ^ Dontenville (1973a, p. 176)

- ^ Société académique de l'arrondissement de Boulogne-sur-Mer (1881, p. 30)

- ^ a b c Société française du folklore français et du folklore colonial (1934, p. 69)

- ^ a b c d Bayart, Marcel. "Creuyances et superstitions" [Creed and superstition]. L'Abeille de la Ternoise (in French). Retrieved 3 December 2009.

- ^ a b c Dubois 2008, pp. 102–103.

- ^ Dontenville (1966, p. 103)

- ^ a b Seignolle (1998, p. 59)

- ^ a b Chevalier & Gheerbrant 1982, p. 226.

- ^ Dubost (1991, p. 446)

- ^ Dontenville (1973a, p. 143)

- ^ Clébert (1971, p. 102)

- ^ Gougaud (1973)

- ^ Labrousse, Nathalie (2003). La fantasy, un rôle sur mesure pour le maître étalon [Fantasy, a tailor-made role for the master stud] (in French). Asphodale. ISBN 2-84727-016-7.

- ^ Sauzeau & Sauzeau (1995, pp. 259–298)

- ^ a b Université Paul Valéry (1979, p. 172)

- ^ Durand (1983, p. 84)

- ^ Vernes et al. (1995, p. 289)

- ^ Brasey (2008, p. 256)

- ^ Doulet, Jean-Michel (2002). Quand les démons enlevaient les enfants : les changelins : étude d'une figure mythique : Traditions & croyances [When demons kidnapped children: changelings: study of a mythical figure : Traditions & beliefs] (in French). Presses de l'Université de Paris-Sorbonne. p. 433. ISBN 9782840502364.

- ^ Martineau, Anne (2003). Le nain et le chevalier: Essai sur les nains français du Moyen Âge : Traditions et croyances [The dwarf and the knight: an essay on medieval French dwarves, traditions and beliefs] (in French). Presses Paris Sorbonne. p. 286. ISBN 9782840502746.

- ^ James-Raoul, Danièle; Thomasset, Claude (2002). Dans l'eau, sous l'eau: le monde aquatique au Moyen Âge [In water, underwater: the aquatic world in the Middle Ages] (in French). Presses Paris Sorbonne. p. 432. ISBN 9782840502166.

Sources[edit]

- Brasey, Édouard (2008). La petite encyclopédie du merveilleux [The little encyclopedia of wonder] (in French). Le pré aux clercs.

- Chevalier, Jean; Gheerbrant, Alain (1982). Dictionnaire des symboles [Dictionary of symbols] (in French).

- Clébert, Jean-Paul (1971). Bestiaire fabuleux [Fabulous bestiary] (in French). Albin Michel.

- Collectif (1810). Mémoires de l'Académie celtique: ou, Mémoires d'antiquités celtiques, gauloises et françaises [Memoirs of the Celtic Academy: or, Memoirs of Celtic, Gallic and French antiquities] (in French). L.P. Dubray.

- Coussée, Bernard (1994). Légendes et croyances en Boulonnais et pays de Montreuil [Legends and beliefs in the Boulonnais and Montreuil regions] (in French). B. Coussée. ISBN 9782905131126.

- Coussée, Bernard (1996a). Le mystère de la lune rousse: essai de mythologie populaire [The mystery of the red moon: an essay in popular mythology]. B. Coussée. ISBN 9782905131157.

- Coussée, Bernard (2006). Les Mystères du Nord-Pas-de-Calais: Histoires insolites, étranges, criminelles et extraordinaires [Mysteries of the Nord-Pas-de-Calais: Unusual, strange, criminal and extraordinary stories] (in French). Éditions De Borée. ISBN 9782844944566.

- Dontenville, Henri (1966). La France mythologique (in French). H. Veyrier.

- Dontenville, Henri (1973a). Mythologie française : Regard de l'histoire [French mythology: View of history] (in French) (2nd ed.). Payot.

- Dubois, Pierre (2008). La Grande Encyclopédie des fées [The Great Fairy Encyclopedia] (in French). Hoëbeke.

- Dubost, Francis (1991). Aspects fantastiques de la littérature narrative médiévale, xiie-xiiie siècles: l'autre, l'ailleurs, l'autrefois [Fantastic aspects of medieval narrative literature, xiie-xiiie centuries: the other, the elsewhere, the formerly] (in French). Paris: Libr. H. Champion.

- Durand, Gilbert (1983). Les structures anthropologiques de l'imaginaire: introduction à l'archétypologie générale [Anthropological structures of the imaginary: an introduction to general archetypology] (in French). Dunod. p. 536.

- Gougaud, Henri (1973). Les Animaux magiques de notre univers [The magical animals of our universe] (in French). Solar.

- Sauzeau, Pierre; Sauzeau, André (1995). "Les chevaux colorés de l'" apocalypse "" [The colorful horses of the apocalypse]. Revue de l'histoire des religions. 212 (3): 259–298. doi:10.3406/rhr.1995.1262.

- Sébillot, Paul (1907). Le folklore de France : Le peuple et l'histoire [French folklore: People and history] (in French). E. Guilmoto, librairie orientale et américaine. ISBN 9780543952974.

- Seignolle, Claude (1998). Les Évangiles du Diable [The Devil's Gospels] (in French). Robert Laffont. ISBN 2-221-08508-6.

- Société académique de l'arrondissement de Boulogne-sur-Mer (1881). Mémoires (in French). Impr. Hamain.

- Société française du folklore français et du folklore colonial (1934). Revue de folklore français et de folklore colonial [Review of French and colonial folklore] (in French). Larose.

- Université Paul Valéry (1979). Mélanges à la mémoire de Louis Michel [Mélanges in memory of Louis Michel] (in French).

- Vernes, Maurice; Réville, Jean; Marillier, Léon; Dussaud, René; Alphandéry, Paul (1995). Revue de l'histoire des religions : Annales du Musée Guimet [Review of the history of religions: Annals of the Guimet Museum] (in French). Presses Universitaires de France.