Wenceslas Bible

| Wenceslas Bible | |

|---|---|

| Vienna, Austrian National Library (Cod. 2759–64) | |

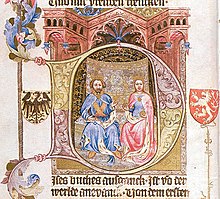

Initial of the book of Genesis – Seven days of creation | |

| Type | Bible |

| Date | 1390s |

| Place of origin | Prague |

| Language(s) | German |

| Illuminated by | Frána Kuthner and others |

| Patron | Wenceslaus, King of the Romans and King of Bohemia |

| Material | Parchment |

| Size | 1,214 leaves |

| Format | 530 x 365 mm |

| Contents | Old Testament (Daniel, Minor Prophets and Maccabees missing) |

| Illumination(s) | 654 miniatures |

The Wenceslas Bible[1] (German: Wenzelsbibel) or the Bible of Wenceslaus IV (Czech: Bible Václava IV.) is a multi-volume illuminated biblical manuscript written in the German language. The manuscript was commissioned by the King Wenceslaus IV of Bohemia (that time also the King of the Romans) and made in Prague in the 1390s. The Wenceslas Bible is unique and very precious not only because of its text, which is one of the earliest German translations of the Bible, but also because of its splendid illuminations. Inside the manuscript contains images relating to 14th century politics as well as images of "Wild Men", an iconographic representation of man's temptation towards barbarism. This oldest German deluxe Bible manuscript[2] remained uncompleted.[1]

Historical context[edit]

The Wenceslas Bible contains the text of one of the earliest Bible translations into German. The translation from the Latin Vulgata was commissioned by the wealthy burgher of Prague Martin Rotlev about 1375–1380.[1]

Although Wenceslas' father Emperor Charles IV forbade Bible translations from Latin into vernacular languages as heresy in 1369,[3] king Wenceslas with his second wife Sophia disrespected his father's order by their patronage of this spectacular edition of the new German Bible translation. Their own patronage confirms an inscription in the manuscript. It indicates the close relationship between the Bohemian royal court and the nascent Bohemian Reformation.[4] This translation project would allow the listener to read and understand the words of the bible in their own language without the need for a priest as intermediary. Additionally, by financing this project, Wenceslas believed that he could have sway over the Catholic world, influencing these new ideas of a Catholic reformation with his own influence.[3]

The Wenceslas Bible was never completed. The Book of Daniel, the Minor Prophets and the Books of Maccabees are lacking from the Old Testament and the New Testament was not even begun. The Bible contains 654 miniatures and initials; some were only scratched. The scribe left free spaces for more than 900 other illustrations. If the Bible were completed, it would have comprised about 1,800 leaves with circa 2,000 illuminations and would accordingly have surpassed all other medieval manuscripts in length, dimensions and wealth of artistic ornament.[1] The Wenceslas Bible would have been more densely decorated than most Gothic Bibles; while most Gothic Bibles would contain only one illustration per book, the Wenceslas Bible had attempted to create an illustration for every chapter in the Bible, so there are 1,189 illustrations in total, nearly eighteen times more than the average Gothic Bible.[5] Sixty years later under Emperor Frederick III of Habsburg, the parts of the Bible that were completed were bound into three volumes, before being divided into six parts due to the volumes being too bulky, with two of these parts containing no illustrations whatsoever.

Production[edit]

The creation of the Wenceslas Bible involved multiple workshops and masters. The primary workshop responsible for the decoration was known as the Seven-Day Master, likely comprising at least four painters, while other illuminators such as Frana, the Solomon Master, and the Esra Master also worked on specific layers.[6] Variations in illustration techniques and page production, credited to different masters, further support the idea of the manuscript's collaborative origin.[6] Evidence for this detailed analysis, draws heavily from the work of researchers such as Julius von Schlosser, Gerhard Schmidt, and Josef Krása, which sheds light on the manuscript's complex authorship and dating.[6]

On the margins of the Bible there is also evidence of instruction from a conceptor, a theologian that acted similar to a creative director, in collaboration with the artists that would ensure the illustrators accurately depicted the word of God.[3] There remains evidence of these instructions in the numerous black spaces unfinished illustrations were meant to go, meaning that these instructions would either be scratched away or have the artist simply paint over the words.

Bible stories would be depicted as a collection of a few images across the page, a process called maeren hort,[3] allowing the protagonist of the story to take up multiple spaces across the page and communicate a non-verbal narrative over a passage of time. For instance, we witness the birth of Esau and Jacob in one section, followed by a scene of them as children walking with their parents below.

The Wenceslas Bible prioritized fidelity to the biblical text in its illustrations over instructing illuminators on how to portray specific figures such as Assyrians, Jews, or Asaph.[3] This approach differed from contemporary practices that often incorporated culturally influenced or anti-Semitic iconography. Thus, the emphasis lay on textual accuracy and avoiding bias as much as possible to keep to the true word of the Bible.

Images[edit]

Most of the images within the Wenceslas Bible are depictions of a Bible story, heraldry or rhetorical themes relating to Bohemia, or sometimes both. The style of the illustrations is generally typical of 14th century Gothic Bohemia, however there are subtle evolutions in style as the production entered the 15th century.[6] Many of the colors used are soft pastel reds, greens, and blues. Flourishes that decorate the borders of the text are often natural shapes such as leaves or flowers. Sometimes these flourishes are subtly interlaced, sometimes much more complexly. The name of the Book or chapter of the Bible being discussed would be at the top of the page portrayed in calligraphy lettering, surrounded by intricate interlacing patterns. Kingfishers and other birds native to the area, stylized or otherwise, were a common motif, often sitting on top of these naturalistic border flourishes directly next to a coat-of-arms representing Bohemia.[3]

The Wild Men[edit]

Hairy figures known as Wild Men preside throughout the margins of the Wenceslas Bible. Medieval art historians such as Studnickova and Antunes have done extensive research regarding the "Wild Men" found as a motif in Medieval art. The Wild Men are figures covered in hair from head to toe, sometimes bald or combed, with human faces.[3] While unique in depiction, they come from a heritage of depiction from more pagan mythos such as Satyrs.[3] Sometimes called Green Men in other contexts, they can refer to a representation of the anxieties faced while traveling through the wilderness during important travel such as a pilgrimage.[3] During travel through this wilderness, people could expect to find a variety of individuals on the outskirts of society such as highwaymen or pagan cultists, allowing this artistic depiction of Wild/Green Men to stand in for their fears of confrontation to these people during this travel.[7][8] While there are definitely cases where Lords or other landowners had more of a direct control over these wild areas if there was something produced in these areas such as beeswax, it was within these forests that provided an opportunity for a shift within the social-hierarchy of the time. Somebody who may be poor and unimportant in a more rural area had the opportunity to wield power through violence over travelers through this undeveloped land.[7] Again, as a general motif found in various European cultures, the Wild Men began to represent a variety of things, in this case the anxiety of encountering someone who may trick or hurt you in an unfamiliar area.[7]

Focusing on 14th century Bohemia, of all the various types of manuscripts commissioned by King Wenceslas, these Wild Men only appear in the Wenceslas Bible, presumably because their depiction is explicitly related to the non-secular text of the Bible.[8] In this context, these wild men represent a variety of more broad symbolic imagery such as libido, passion, impurity and freedom or the lack thereof, and often use this symbolism along with stories in the Bible to reference contemporary political events.[8]

The motifs of Wild Men within the Wenceslas Bible appear to carry distinct meanings,[8] each contributing to the broader narrative. For example, within the marginalia, there are depictions of Wild Men holding the coat of arms of Bohemia and other countries,[3] while in other instances, King Wenceslas himself is depicted alongside these figures, such as during Wenceslas' bathing scene.[3]

When depicted alongside the King these Wild Men may symbolize Wenceslas' leadership qualities, suggesting his ability to navigate his kingdom towards civility and strength[3]. Moreover, the presence of the King in the company of Wild Men may also convey notions of his own virility,[3] serving as a visual representation of his potency and authority, often associated with his ability to guide his kingdom towards prosperity. More broadly and most notably, the motif of hair, whether on the head or body, and its grooming is often associated with notions of health and spiritual purity.[8] Additionally, some motifs are linked to themes of service or disobedience to God, as well as cultural distinctions such as tribes, lands, peoples, and languages.[8] Perhaps most significantly, the portrayal of Wild Men engaging in political symbolism, often through the display of coats of arms, particularly that of Bohemia, underscores their role in reflecting contemporary political tensions through biblical imagery.

Overall, the Wild Men tend to represent man's tendency towards barbarism and God or the King's power to bring humanity towards civilization and salvation.[8]

Gallery[edit]

-

Kingfisher – the personal emblem of Wenceslas IV

-

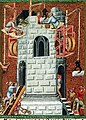

Construction of the Tower of Babel

-

Creation of Eve

-

Female bath attendants washing King Wenceslas

-

Coat of Arms of 14th Century Bohemia

-

The Birth of Jacob and Esau

References[edit]

- ^ a b c d Boehm, Barbara Drake; Fajt, Jiří, eds. (2005). Prague: The Crown of Bohemia, 1347–1437. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art. pp. 220–222. ISBN 9780300111385.

- ^ "The Wenceslas Bible – Complete Edition". www.adeva.com. Akademische Druck- u. Verlagsanstalt Graz. Retrieved 12 June 2014.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m Theisen, Maria. Luxembourg Court Cultures in the Long Fourteenth Century. pp. 246–320.

- ^ Boehm, Barbara Drake; Fajt, Jiří, eds. (2005). Prague: The Crown of Bohemia, 1347–1437. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art. p. 99. ISBN 9780300111385.

- ^ Morgan, N. (2003). Wenceslas Bible. Grove Art Online

- ^ a b c d Jenni, Ulrike; Theisen, Maria (2014). Mitteleuropäische Schulen IV (ca. 1380-1400): Hofwerkstätten König Wenzels IV. und deren Umkreis (1 ed.). Austrian Academy of Sciences Press. ISBN 978-3-7001-7203-1.

- ^ a b c JOANA FILIPA FONSECA ANTUNES. METAMORPHOSIS OF THE GREEN MAN AND THE WILD MAN IN PORTUGUESE MEDIEVAL ART. In: Ideology in the Middle Ages. Arc Humanities Press; 2019:333-. doi:10.2307/j.ctvsf1p0g.20

- ^ a b c d e f g STUDNIČKOVÁ, Milada. Gens Fera: The Wild Men in the System of Border Decoration of the Bible of Wenceslas IV. Umění: časopis Ústavu dějin umění Akademie věd České republiky. Praha: ČSAV, 2014, 62(3), 214-239. ISSN 0049-5123.