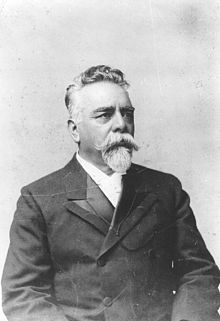

Presidency of Campos Sales

| |

| Presidency of Campos Sales 15 November 1898 – 15 November 1902 | |

Vice President | |

|---|---|

| Party | PRP |

| Election | 1898 |

| Seat | Catete Palace |

|

| |

The presidency of Campos Sales began on 15 November 1898, after he won the 1898 Brazilian presidential election, the 3rd presidential election held in Brazil, becoming the country's 4th President; and ended on 15 November 1902, when Rodrigues Alves took office.

Campos Sales' government marked an era of transition in Brazil's political history. The Governors' Policy, financial stabilization and international relations are key aspects of this period. While his government was instrumental in stabilizing Brazil's economy with the first Funding Loan, it also consolidated an oligarchic political system that would later generate significant challenges.

Campos Sales is remembered as a president who, at a critical moment in Brazilian history, sought to balance economic needs with the political demands of regional elites. The young First Brazilian Republic, which had been proclaimed in 1889, was still consolidating its structure and faced critical periods and challenges.

During his term, with a strong concern for the country's finances, and with austerity measures, Brazil's GDP grew on average 3.1% per year.

Background[edit]

1898 presidential election[edit]

On 1 March 1898, Campos Sales was elected President of Brazil, with the support of then president Prudente de Morais, he received 420,286 votes against 38,929 votes from his main opponent, the positivist Lauro Sodré, a candidate most supported by Floriano Peixoto's followers and the positivists, already having served as governor of Pará from 1891 to 1896.[1] His vice-president was Francisco de Assis Rosa e Silva. Campos Sales took office on 15 November 1898, succeeding Prudente de Morais.[2]

Negotiating the foreign debt[edit]

In April 1898, after the electoral result, Campos Sales travelled to Europe with the goal of addressing the serious issue of the country's external debt.[3] For around two months, alongside Bernardino de Campos, then Prudente de Morais' Minister of Finance, negotiations began with representatives of the Rothschild Firm, the main creditor of Brazilian debt, resulting in the approval of a consolidation loan (called Funding Loan).[4] From this negotiation came the final agreement that secured a new loan of £10 million. In exchange, the Brazilian government gave the income from the Rio de Janeiro customs as a guarantee, and committed itself not to resort to new external loans.[3] It was also expected that the Brazilian authorities would incinerate a quantity of paper money equivalent to the loan.[3]

Presidency[edit]

Domestic policy[edit]

At the time, the Brazilian economy, based on the export of coffee and rubber, was in the aftermath of the Encilhamento crisis. Campos Sales believed that all of Brazil's problems had a single cause: the devaluation of its currency.[5] He defined his government as disconnected from party political interests, thus expressing his administrative vision, he sought to choose technicians not linked to party politics for his ministries, and was inspired by the advice of American president Benjamin Harrison to organize his cabinet. In the book Da Propaganda à Presidência, Campos Sales cited Harrison's book called Government and Administration of the United States.[6]

In practice, however, Campos Sales typically represented the political ideals of each state's dominant oligarchies. In return, he received political support from state factions in Congress. With the creation of the Chamber of Deputies' Powers Verification Commission, the congressmen themselves legitimized the election of representatives and thus only elected representatives who were appointed by the state governors were sworn in.[7] The result of this pact was the weakening of opposition factions, electoral fraud and the exclusion of the majority of the population from any political participation. Oligarchic political control was also ensured by open voting and the recognition of elections not by the Judiciary branch, but by the Legislative branch itself. As Congress was influenced by the president and state governors, this mechanism gave rise to the so-called "beheading" of undesirable candidates.[7] Campos Sales remarked:[8]

I understood that I had to dedicate my government to a purely administrative work, separating it from partisan interests and passions, only to take care of solving the complicated problems that are the legacy of a long past. I understood that it would not be through the incandescent vivacity of political struggles, which were pointless, that I would be able to save the nation's finances, compromised due to a debt with external creditors!

Governors' Policy[edit]

Campos Sales devised his States' Policy, better known as the Governors' Policy, through which he removed the military from politics (who had held the presidency since the proclamation of the republic) and established the oligarchic system of Brazil's First Republic, declaring that:

In this regime, I said in my last message, the true political force, which in the strict unitarism of the [Brazilian] Empire resided in the central power, moved to the States. The States' Policy, that is, the policy that strengthens the bonds of harmony between the States and the Union, is therefore, in essence, a national policy. It is there, in the sum of these autonomous units, that the true sovereignty of opinion is found. What the States think, the Union thinks.

Through the States' Policy, Campos Sales obtained the support of Congress through relationships of mutual support and political favor between the central government, represented by the president, and the states, represented by their respective governors, and municipalities, represented by local bosses.[9] The autonomy and independence of municipal and state governments was preserved, as long as the municipal governments supported the state governments and these, in turn, supported the federal government. With this way of governing, Campos Sales achieved political stability in the country.[5] This stability was achieved through the manipulation of results through the Powers Verification Commission, formed by federal deputies.[7] The president had control over it. From then on, electoral fraud was committed by the commission itself, which only recognized the governor's candidates as elected. This was dubbed the "beheading" of the opposition, which from then on found itself unable to win elections. This policy had previously been initiated and tested when Campos Sales, as governor of São Paulo, guaranteed the power of local bosses as long as they joined the Republican Party of São Paulo and supported the state governor.[5]

Milk coffee politics[edit]

Campos Sales also managed to establish a balance of power between the states with the alternation of Minas Gerais and São Paulo residents in the presidency and vice-presidency, called "milk coffee politics".[10]

Economy[edit]

In the economy, the Campos Sales administration decided that solving the external debt problem was the first step to be taken. In London, the president and the British established an agreement, known as the Funding Loan.[11] With this agreement, the payment of interest on the debt was suspended for three years; payment of existing external debt was suspended for thirteen years; the value of interest and unpaid installments would be added to the already existing debt; the Brazilian external debt would begin to be paid in 1911, for a period of 63 years and with interest of 5% per year; and the income from customs in Rio de Janeiro and Santos would be mortgaged to British bankers as a guarantee.[11]

Then, freed from payment of installments, Campos Sales was able to carry out his policy of economic "sanitation". He fought inflation by no longer issuing money and removing part of the paper money issued by previous governments from circulation.[12] Then he tackled budget deficits, reducing spending and increasing revenue. Joaquim Murtinho, Minister of Finance, reduced the Federal Government's budget, raised all existing taxes and created others.[12] Thus, he achieved a surplus of 38 billion réis in the first year of government, while São Paulo's agriculture suffered a loss of 440 billion réis.

Campos Sales received the nickname "Campos Selos", for having created the so-called "stamp tax" and increased taxes.[13] Finally, he dedicated himself to raise the exchange rate from a 48 thousand-reis per pound to 14 thousand-reis per pound. His policy was accused of being extremely recessive — in more modern terms — and called "forced stagnation", at the time. It was the first time since Brazil's independence that the currency had appreciated, however the results proved tragic: the price of foreign products in Brazil decreased, but the country's industry, already weakened, began to face greater competition from imported goods, resulting in the closure of factories while others reduced their production.[13] Although Campos Sales and his minister Joaquim Murtinho policies stabilized finances, it profoundly harmed industry and the population's living standards.

Foreign policy[edit]

Argentina[edit]

In 1899, the president of Argentina, Julio Argentino Roca, visited Rio de Janeiro. A year later, in 1900, Campos Sales retributed the visit, being received by a large crowd in Buenos Aires, with around 300,000 people from the total 1.2 million inhabitants of the Argentine capital.[14] Campos Sales was the first Brazilian president to travel abroad.[15]

Amapá Question[edit]

The Amapá Question was a territorial dispute between France and Brazil over the issue of delimiting the border between French Guiana and the current Brazilian state of Amapá, where the vast territory was claimed by the two countries dating back to the Treaty of Utrecht of 1713, delimiting the areas belonging to France and Portugal. Portugal, and later Brazil, argued that the entire area of the northern basin of the Oyapock River belonged to them, while the French claimed the interior of the territory.[16] After decades of dispute, the Baron of Rio Branco was entrusted with an arbitration treaty, seeking to put an end to the disagreements regarding territorial delimitation. The Baron had noted that the United Kingdom also had an interest in the area, and did not wish to see France dominating the entire Guiana region through territory claimed by French colonists, threatening its own colony of British Guiana by surrounding it from the south.[16]

The protocol of 1 April 1897, signed between the two governments, more or less precisely determined the limits of the disputed territory. The French Government tried to introduce the possibility of the arbitrator resorting to a transaction, but Brazil insisted that this be restricted to eliminating ambiguities over the territory, in particular the Oyapock River. The facts were definitively resolved with the Swiss arbitration ruling in favor of Brazil, the conclusions of which were announced on 1 December 1900 by Walter Hauser.[16]

End of the presidency[edit]

Campos Sales governed until 15 November 1902, and managed to appoint his successor, electing, on 1 March 1902, Rodrigues Alves, from São Paulo, as president of Brazil, and as vice-president, Silviano Brandão, from Minas Gerais, who died before taking office, being replaced by Afonso Pena. Campos Sales' government was not popular with public opinion. Upon leaving the presidency, he was booed as he walked from the presidential palace to the train station.[13]

References[edit]

- ^ "A ciência do governar: positivismo, evolucionismo e natureza em Lauro Sodré" (PDF). Repositório UFPA. 2006.

- ^ Porto, Walter Costa (2002). O voto no Brasil. Topbooks.

- ^ a b c Abreu, Marcelo de Paiva (2002). "Os Funding Loans Brasileiros — 1898-1931". Pesquisa e Planejamento Econômico. 32 (3).

- ^ "Bernardino José de Campos Júnior". Portal da Câmara dos Deputados (in Portuguese). Retrieved 2023-11-01.

- ^ a b c "Campos Sales". Estadão (in Portuguese). Retrieved 2023-11-01.

- ^ Borges, Alexandre. "O Brasil está preparado para um estadista?". Gazeta do Povo (in Portuguese). Retrieved 2023-11-01.

- ^ a b c "Comissão de verificação de poderes" (PDF). FGV CPDOC.

- ^ Campos Sales, Manuel Ferraz de (1983). Da Propaganda à Presidência. Editora UNB.

- ^ Leal, Victor Nunes (1949). Coronelismo, Enxada e Voto. Rio de Janeiro: Forense.

- ^ "Política do café-com-leite - Acordo marcou a República Velha".

- ^ a b "Funding Loans | Atlas Histórico do Brasil - FGV". atlas.fgv.br. Retrieved 2023-11-01.

- ^ a b "Joaquim Duarte Murtinho". Ministério da Fazenda (in Portuguese). Retrieved 2023-11-01.

- ^ a b c "Folha de S.Paulo - Brasil 500 d.c. - José Murilo de Carvalho: Aconteceu em um fim de século". www1.folha.uol.com.br. Retrieved 2023-11-01.

- ^ "As origens da diplomacia presidencial na relação entre o Brasil e a Argentina: as visitas do presidente Julio Roca ao Rio de Janeiro (1899) e do presidente Campos Sales a Buenos Aires (1900) - IHGB - Instituto Histórico Geográfico Brasileiro". ihgb.org.br (in Portuguese). Retrieved 2023-11-02.

- ^ "Declarações de bolsonaristas indicam que relações entre Brasil e Argentina estão indo ladeira abaixo". Época (in Portuguese). 2018-11-06. Retrieved 2023-11-02.

- ^ a b c "O Arbitramento No Amapá". artigos.netsaber.com.br. Retrieved 2023-11-02.