78th Brigade (United Kingdom)

| 78th Brigade | |

|---|---|

| Active | 13 September 1914–10 May 1919 |

| Allegiance | |

| Branch | |

| Type | Infantry |

| Size | Brigade |

| Part of | 26th Division |

| Engagements | Battle of Horseshoe Hill Second Battle of Doiran Pursuit to the Strumica Valley |

The 78th Brigade (78th Bde) was an infantry formation of the British Army during World War I. It was raised as part of 'Kitchener's Army' and was assigned to the 26th Division. It served on the Salonika Front, capturing Horseshoe Hill in 1916 and fighting in the disastrous Second Battle of Doiran in 1917. At the end of the war it spearheaded the pursuit of the defeated enemy and took part in the postwar occupation of Bulgaria before it was disbanded in 1919.

Recruitment and training[edit]

On 6 August 1914, less than 48 hours after Britain's declaration of war, Parliament sanctioned an increase of 500,000 men for the Regular British Army. The newly-appointed Secretary of State for War, Earl Kitchener of Khartoum, issued his famous call to arms: 'Your King and Country Need You', urging the first 100,000 volunteers to come forward. This group of six divisions with supporting arms became known as Kitchener's First New Army, or 'K1'.[1][2] The K2 and K3 battalions, brigades and divisions quickly followed: 26th Division, containing 77th, 78th and 79th Brigades, was authorised on 13 September as part of K3. Brigadier-General E.A.D'A. Thomas was appointed to command 78th Bde on 25 September. The brigade assembled around Codford St Mary and Sherrington on the edge of Salisbury Plain.[3][4][5]

As the junior division of K3, there were no khaki uniforms available for the men, who were clothed in any makeshift uniforms the clothing contractors could find. Later it became possible to issue a form of blue uniform. It took longer to obtain drill-pattern rifles and accoutrements, but barrack-square training continued until the weather worsened at the end of October, turning the drill ground and tent floors into a sea of mud. In November the division was dispersed into billets, with the battalions of 78th Bde returning to their home areas of Cheltenham, Worcester, Oxford and Reading. The men now had drill rifles for training, and khaki uniforms and equipment arrived between February and April 1915. Between 26 April and 8 May the units returned to Salisbury Plain and were concentrated in huts between Sutton Veny and Longbridge Deverill near Warminster. Brigade training could now begin, and the drill rifles were slowly replaced by Short Magazine Lee–Enfield Mk III service rifles. Divisional training started in July, followed by final battle training. The division completed its mobilisation on 10 September and was ordered to France to join the British Expeditionary Force on the Western Front. The first advanced parties left on 12 September, 7th Worcestershire Regiment landed at Le Havre on 20 September and the rest of 78th Bde's units landed at Boulogne the following day. By 23 September the division had completed its concentration around Guignemicourt, west of Amiens. [3][4][5]

Order of Battle[edit]

The composition of 78th Brigade was as follows:[3][4][5][6][7]

- 9th (Service) Battalion, Gloucestershire Regiment – to Western Front 4 July 1918

- 11th (Service) Battalion, Worcestershire Regiment

- 7th (Service) Battalion, Oxfordshire & Buckinghamshire Light Infantry (OBLI)

- 7th (Service) Battalion, Royal Berkshire Regiment

- 78th Machine Gun (MG) Company, Machine Gun Corps – formed at Grantham, embarked at Devonport 5 July 1916; disembarked at Salonika 14 July and joined brigade 22 July

- 78th Trench Mortar Battery (TMB) – manned by detachments from the infantry; joined 12 November 1916

- 78th Small Arms Ammunition (SAA) Section – manned by the Royal Field Artillery; numbered 23 March 1916; detached from Divisional Ammunition Column (DAC) and joined brigade by 27 July 1916

Service[edit]

From 28 September 1915 the brigades and battalions of 26th Division were attached to units already in the line for their introduction to Trench warfare. Then on 31 October the division was ordered to Marseille to embark for another theatre. Entrainment began at Flesselles on 9 November and embarkation two days later, with the division expecting to be sent to Egypt. However, the destination was changed to the Macedonian front, and ships carrying elements of the division. began to arrive at Salonika on 23 November. On 26 December the first units moved out of the Salonika base area to Happy Valley Camp, where the division completed its concentration on 8 February 1916.[3][4][5][8]

Horseshoe Hill[edit]

When the Allies moved out of their entrenched camp in April 26th Division. remained behind as Army Reserve and for road construction. Because of the movement difficulties in the mountainous terrain, the British Salonika Army (BSA) reorganised its transport to rely on pack mules. One result of this was that by July the reorganised brigade SAA sections were detached from the DAC and attached to the brigades they served. In August 26th Division moved up to the Lake Doiran sector of the front. On 17 August the French attacked up the west side of the lake (the |First Battle of Doiran), with 78th Bde assisting.The brigade thus carried out the first British offensive operation in the campaign. The British objective was to take Horseshoe Hill and the night attack was entrusted to 7th OBLI supported by the 78th MG Company and two sections of 131st Field Company, Royal Engineers (RE). The plan was for A and B Companies of the OBLI to take the flanking trenches C1 and C3, and then to attack the central position on the hill, C2; C and D Companies would act as carrying parties. To avoid alerting the enemy there would be no preliminary artillery barrage. The assaulting parties assembled at 20.30 in a ravine about 2.5 miles (4.0 km) from Horseshoe Hill, but their advance to contact was delayed by trouble with the mules and the attack was postponed from 22.30 to 23.15, by which time the moon had risen. A French officer had reconnoitred C3 during the afternoon and declared that it was unoccupied, but the assaulting party went forward cautiously, and was met by heavy fire. The trenches on C1 and C3 had been almost obliterated by artillery fire over the previous week, but they were covered by fire from C2. With the support of 78th MG Company, both flanking positions were taken, but runners had to go back to request artillery support before C2 could be captured, which required all four companies of the OBLI. The Bulgarian trench on the crest of the hill proved to be untenable, so the garrison established a position some 70 yards (64 m) down the reverse slope, leaving only a lookout post on the crest. The hill was under artillery fire all next day, but the infantry and REs had partially dug in and wired the position before the first counter-attack arrived early on 19 August. The Bulgarians charged down from 'Pip Ridge' in front, and tried to get round the fresh wire, suffering heavy casualties from the OBLI's rapid rifle fire. A second attack was also beaten off, after which the Bulgarians conceded the hill, though subjecting it to intense shellfire. 7th OBLI was relieved by 9th Gloucesters early on 20 August, having suffered 105 casualties in the three days. After the Battle of Horseshoe Hill the British west of Lake Doiran conducted a holding operation for the rest of the year, with numerous raids to pin down the Bulgarians. 78th Brigade carried out a raid on the night of 10 February 1917 against a Bulgarian outpost on Hill 380, overlooking the Jumeaux Ravine. A party from 7th Berkshires set out but went 2 minutes too early and suffered casualties from their own artillery fire: losses (including RE and TMB personnel) were 34, and the Bulgarians had evacuated the post during the night and so no prisoners or identification could be obtained.[3][4][7][9][10][11]

Second Battle of Doiran[edit]

In March and April 1917 the BSA was repositioned in preparation for an offensive in the Doiran sector. 26th Division was now one of the more experienced in the theatre, and was given a wide front of about 8,000 yards (7,300 m) (although part of it was covered by the lake). It advanced without opposition on the night of 9/10 March to take over the mounds known as the Whale Back and Bowls Barrow. The main attack (the Second Battle of Doiran) was carried out at dusk on 24 April after three days of artillery fire to cut the Bulgarian barbed wire. 26th Division attacked with 78th and 79th Bdes in line. 78th Brigade on the left had 7th Berkshires and 11th Worcesters in front, directed towards positions O5 and O6 on the precipitous northern slope of Jumeaux Ravine between the Petit Couronné and Hill 380. The 7th Berkshires attacked towards O5 with three companies, the first two to capture the enemy's front line trench, the third to pass through and assault two isolated works behind the left section. The right company was stopped by the enemy's barrage, but the other two carried their objectives and began to consolidate them. 11th Worcesters on their left had hardly began its climb out of the Senelle Ravine when it came under heavy fire, causing numerous casualties and temporary disorganisation. The battalion pushed on, however, formed up, and launched its assault on time. The right company was driven back by bombs and machine gun fire from the circular Redoubt that was its objective, but the left company captured the trench west of it and drove off a determined counter-attack at 22.15. It also cleared a communication trench at right angles to the fire trench, and blocked the fire trench 20 yards (18 m) from the redoubt. The support companies now came up and fierce struggle followed, swaying back and forth. At 01.15 9th Gloucesters in brigade support was ordered to send a company up to reinforce 11th Worcesters. This company passed through the barrage with heavy losses, but reached the Worcesters on O6; a second company went forward at 02.05, but does not appear to have reached the trenches. After the Worcesters drove off two counter-attacks both battalions were forced to fall back between 03.45 and 04.00. Only two companies of 10th Devonshire Regiment of 79th Bde were left on the Petit Couronné, and they were recalled at 04.00, just as carrying parties (including some from 7th OBLI) finally arrived with bombs and ammunition. The whole attack of 26th Division had been a complete and costly failure. After daylight unarmed parties of the two brigades went into Jumeaux Ravine to collect wounded. Although there was some firing against them, they were generally allowed to bring in most of the wounded.[3][4][12][13]

The battle was renewed on the night of 8/9 May. The attacking brigades had practised the assault over taped-out representations of the enemy line. Just before the action the commander of 22nd Division was evacuated sick and Brig-Gen Duncan of 78th Bde temporarily replaced him; Lieutenant-Colonel T.N.S.M. Howard of 10th Devonshires took over 78th Bde. These appointments were later made permanent. For this attack 26th Division avoided Jumeaux Ravine and employed 77th Bde on the right to attack O1, O2 and O3, reinforced by 9th Gloucesters from 78th Bde and the divisional pioneer battalion (8th OBLI). 78th Brigade was also ordered to keep a battalion in readiness to make a follow-up attack on the Petit Couronné (O4) and then O5. Late on 8 May the plan for the extension to O5 was changed, and two companies of 7th Berkshires were assigned to carry it out, but they did not receive the orders until 17.00. 77th Brigade's attack was a failure, but this was not known when 7th OBLI launched the follow-up. It attacked with three companies and six Lewis guns, supported by two pioneer platoons from 8th OBLI. A company of 7th Berkshires took over the OBLI's trenches when 7th OBLI went forward at 10.50, followed by the pioneers and its reserve company carrying ammunition, bombs and water. They crossed the Jumeaux Ravine more quickly than expected, and began to suffer casualties while they waited for Zero (00.20). At 23.57 Lt-Col Howard received a message from Major A.D. Homan commanding the leading companies that they were going to attack in 10 minutes. Howard did not think it was possible to change the artillery programme at such short notice, and ordered Homan to stick to the programme, attacking as planned at 00.20. His message was received, but probably too late, and at 00.13 an artillery observer reported that the attack had started, the men scrambling up the steep slope. Although part of the barrage was successfully called off, some shells from heavy guns fell in O4 at 00.20 and caused casualties and confusion. During the advance Maj Homan and almost all the company officers were wounded, leaving a 2nd Lieutenant in command until Maj C. Wheeler could come up with the reserve company. Reinforced by this company and the pioneers, the battalion gained a lodgement in the south-eastern corner of O4 and made four attempts to advance from there. Each attack was halted by a trench mortar barrage, under cover of which the Bulgarians crept forward and counter-attacked. Communications broke down, with all wires cut, lamp signals obscured by smoke, and most runners being killed. Reporting the situation to divisional HQ, Howard was ordered at 02.00 to make good the position at O4 and attempt nothing more. By then Wheeler had two wounded officers and about 150 men clinging to the corner of O4. The two Berkshire companies had left the British trenches at 01.30, crossed the Jumeaux Ravine almost without loss and formed up in two lines south of O4. By the tim they arrived there were only a handful of 7th OBLI left, having been forced out of O4 and were holding on 50 yards (46 m) south of it. Howard later sent a third company of 7th Berkshires up. (By now 77th Bde was planning a second assault, including 9th Gloucesters, but the attack was postponed several times. 9th Gloucesters advanced alone, entering O2 and finding it empty apart from Bulgarian dead, but under fire from O1; they were then recalled.) Lieutenant-Col A.P. Dene of 7th Berkshires led his third company up himself with Howard's orders to renew the attack on O4. He reorganised the troops on Petit Couronné, putting the first two Berkshire companies in the lead, followed by the third company and the remnant of 7th OBLI. After a half-hour bombardment Dene attacked at 05.00, taking almost all of O4; a bombing party even worked its way along a communication trench half way to O5. The Bulgarians now poured artillery fire onto the position and counter-attacked from O5, forcing the British back some distance. The survivors (about 250) established an east–west line across the middle of the O4 position; Lt-Col Dene having been evacuated wounded, Lt-Col A.T. Robinson of 7th OBLI took command on the spot. It was now 08.30, and the Bulgarian bombardment opened up again. All the other attacks having failed, it was hopeless to expect these isolated survivors to be able to maintain their position, and at 12.05 they were ordered to retire. Lieutenant-Col Robinson having been mortally wounded, Captain S.A. Pike of the Berkshires took command, sending the men down Tor Ravine in parties of 12, taking with them all of the wounded from the heights, as well as all the remaining bombs and ammunition.[3][4][14][15]

The BSA settled down once more to trench warfare and raids through the autumn and winter. In January 78th Bde established a small farm to bring abandoned land back into cultivation. and ease the supply problems.The crisis on the [[Western Front after the German spring offensive in early 1918 led to urgent calls for reinforcements to be sent from other theatres. In June the BSA was required to send 12 infantry battalions, one from each of its brigades: 9th Gloucesters was sent from 78th Bde. As well as this loss of manpower, the BSA was crippled by malaria, which left many of the troops in hospital during the summer months. In September an outbreak of Spanish flu left many units unfit for action.[3][4][5][16][17]

Pursuit[edit]

Preparations began in August 1918 for a new offensive in the autumn. The Third Battle of Doiran began on 18 September with attacks by British and Greek troops on either side of Lake Doiran. 22nd Division, reinforced by 77th Bde from 26th Division, was given the responsibility for the attack on the west side, but in two attacks on 18 and 19 September it failed in its objectives. In spite of the disaster at Doiran, the Allies were making good progress elsewhere along the Macedonian Front, and enemy forces were crumbling. The Bulgarians began to retreat on 21 September, and the pursuit was led in the British sector by the fittest troops, 78th and 79th Bdes of 26th Division. During the night of 21 September the division occupied the enemy's front line trenches in the Macukovo salient, and patrols sent out next morning found only weak rearguards. 26th Division was ordered to concentrate and prepare to advance up the Struma Valley. On 23 September 78th Bde followed the cavalry of the Derbyshire Yeomanry and occupied the Schwarzberg; next day they reached the River Bajima, another 10 miles (16 km) along appalling roads having left the artillery and transport far behind, with the troops eating their iron rations or captured supplies. At intervals rearguards with artillery and machine guns held up the pursuit: approaching Izlis through a gorge, the advanced guard of 7th OBLI was hit by machine gun fire from three commanding peaks. Attempts to rush them proved fruitless, and the infantry had to stay in cover while the Lewis guns and Vickers guns of 78th MG Company engaged the rearguard. Eventually the Bulgarians withdrew after a howitzer was brought up to shell them and Greek troops threatened their rear. On 25 September the division's leading troops moved through Valandovo and crossed the Serbia–Bulgaria border. They occupied Strumica and secured the bridge over the River Strumica next day. On 24 September the Bulgarians had requested a ceasefire, and the Armistice of Salonica was signed on 29 September. When it came into force on 30 September 26th Division was occupying a line from Gradosar to Hamzali, with HQ at Dragomir.[3][4][18][19]

On 6 October 26th Division began a march across Bulgaria towards the River Danube to continue operations against Austria–Hungary. It reached Kocherinovo on 18 October, but was then redirected towards the Turkish frontier. The brigades entrained at Radomir for Mustafa Pasha, west of Adrianople, 78th Bde arriving on 23 October. However, the Turks were also seeking peace and a bold plan for 26th Division to seize Adrianople by Coup de main was rejected. The Ottoman Empire signed the Armistice of Mudros on 30 October. On 2 November 26th Division was ordered to resume its advance to the Danube, but next day the Austrians signed the Armistice of Villa Giusti.[3][4][20][21]

With hostilities over, 26th Division remained in Bulgaria as part of the Allied occupation force. At the end of the year 78th Bde was operating as a semi-independent brigade group stationed at Dobric in the Dobruja region. Demobilization began in February 1919 and proceeded rapidly. Italian troops began taking over 26th Division's responsibilities from April and on 19–22 April a composite brigade from the division left for service in Egypt. 26th Division and its formations ceased to exist on 10 May 1919.[3]

78th Brigade was not reactivated during World War II.[22]

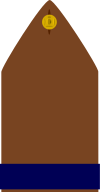

Insignia[edit]

All units of 26th Division wore a simple blue tape across the base of the shoulder straps, introduced as the divisional sign in July 1916. No brigade or battalion distinctions were worn.[23] However, when the division was first formed and no uniforms or regimental badges were available, the battalions in each brigade were temporarily distinguished by a coloured cloth patch in buff, blue, white or green.[3]

Commanders[edit]

The following officers commanded 78th Brigade during its service:[3][6]

- Brigadier-General E.A.D'A. Thomas, 25 September 1914 to 16 April 1916

- Brig-Gen John Duncan, 26 April 1916 to 13 January 1917; returned 22 February 1917, to 7 May 1917

- Col W.L. Rocke, acting 13 January to 22 February 1917

- Lt-Col T.N.S.M. Howard, temporary 7 May 1917, promoted Brig-Gen 22 May 1917, to 11 September 1917; returned 5 November 1917 to 11 April 1918

- Lt-Col G.H.F. Wingate, acting 11 September to 5 November 1917; promoted Brig-Gen 11 April 1918 to Armistice

Notes[edit]

- ^ War Office Instructions No 32 (6 August) and No 37 (7 August).

- ^ Becke, Pt 3a, pp. 2 & 8.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m Becke, pp. 143–9.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j 26th Division at Long, Long Trail.

- ^ a b c d e James, pp. 72–3, 85, 89–90.

- ^ a b Falls, Vol I, Appendix 2.

- ^ a b "Worcestershire Regiment (29th/36th of Foot)". Retrieved 30 November 2014.

- ^ Falls, Vol I, p. 85.

- ^ Falls, Vol I, pp. 111–3, 125–7, 148, 154–6, 162, 251, Sketches 3–5, Appendix 4.

- ^ Wakefield & Moody, pp. 56–9.

- ^ "2nd Lieut. JTS Hoey - Croix de Guerre". Retrieved 30 November 2014.

- ^ Falls, Vol I, pp. 306–11, Sketch 13.

- ^ Wakefield & Moody, pp. 71–9.

- ^ Falls, Vol I, pp. 320–8, Sketch 14.

- ^ Wakefield & Moody, pp. 84–7, 89–92.

- ^ Falls, Vol II, p. 94.

- ^ Wakefield & Moody, pp. 151–2.

- ^ Falls, Vol II, pp. 202–12, 226–32.

- ^ Wakefield & Moody, pp. 220–5.

- ^ Falls, Vol II, pp. 262–7, 279.

- ^ Wakefield & Moody, pp. 225–7.

- ^ Joslen, p. 305.

- ^ Hibberd, p. 26.

References[edit]

- Maj A.F. Becke,History of the Great War: Order of Battle of Divisions, Part 3a: New Army Divisions (9–26), London: HM Stationery Office, 1938/Uckfield: Naval & Military Press, 2007, ISBN 1-847347-41-X.

- Capt Cyril Falls, History of the Great War: Military Operations, Macedonia, Vol I, From the Outbreak of War until the Spring of 1917, London: Macmillan, 1933/London: Imperial War Museum & Battery Press, 1996, ISBN 0-89839-242-X/Uckfield: Naval and Military Press, 2011, ISBN 978-1-84574-944-6.

- Capt Cyril Falls, History of the Great War: Military Operations, Macedonia, Vol II, From the Spring of 1917 to the End of the War, London: Macmillan, 1935/London: Imperial War Museum & Battery Press, 1996, ISBN 0-89839-243-8/Uckfield: Naval and Military Press, 2011, ISBN 978-1-84574-943-9.

- Mike Hibberd, Infantry Divisions, Identification Schemes 1917, Wokingham: Military History Society, 2016.

- Brig E.A. James, British Regiments 1914–18, London: Samson Books, 1978, ISBN 0-906304-03-2/Uckfield: Naval & Military Press, 2001, ISBN 978-1-84342-197-9.

- Lt-Col H.F. Joslen, Orders of Battle, United Kingdom and Colonial Formations and Units in the Second World War, 1939–1945, London: HM Stationery Office, 1960/London: London Stamp Exchange, 1990, ISBN 0-948130-03-2/Uckfield: Naval & Military Press, 2003, ISBN 1-843424-74-6.

- Alan Wakefield and Simon Moody, Under the Devil's Eye: Britain's Forgotten Army at Salonika 1915–1918, Stroud: Sutton, 2004, ISBN 0-7509-3537-5.