Limbic-predominant age-related TDP-43 encephalopathy

Limbic Predominant Age-Related TDP-43 Encephalopathy (LATE)

Limbic-predominant Age-related TDP-43 Encephalopathy, commonly abbreviated as LATE, is a neurodegenerative disease that affects persons of advanced age. In terms of symptoms, LATE mimics clinical features of Alzheimer's disease, often leading to diagnostic confusion. Unlike Alzheimer’s disease, which is driven by amyloid-beta plaques and tau protein tangles, LATE involves TDP-43 proteinopathy that primarily impact the medial temporal lobe regions, which include structures critical for memory. Thus, LATE is a common contributor to the dementia clinical syndrome. The definitive diagnosis of LATE requires neuropathologic examination at autopsy.

LATE is a very common disease among the elderly, impacting approximately one-third of individuals over the age of 85 years. Because LATE is relatively recently defined, often mimicking the clinical signs of Alzheimer’s disease, and still lacking reliable biochemical markers identified in living subjects, many affected individuals are still not diagnosed with LATE until brain autopsy. The similarity in symptomatic presentation to Alzheimer’s disease and the frequent coexistence of LATE with other conditions including Alzheimer’s and cerebrovascular disease, further complicates accurate diagnosis and management, hindering the development of adequate treatment and care strategies.

From a public health perspective, understanding LATE better is crucial as the disease affects a large segment of the aging population(3), leading to substantial healthcare and caregiving burdens. Researchers around the world are racing to improve diagnostic accuracy through potential biomarkers, and to explore therapeutic avenues, enhancing outcomes and quality of life for affected individuals and their families. As therapeutic strategies evolve, especially for Alzheimer’s disease, distinguishing LATE becomes even more pivotal to tailor interventions effectively (for both LATE and Alzheimer’s disease) and improve prognostic accuracy in the geriatric population(4).

Classification

LATE is a neurodegenerative disorder predominantly characterized by the pathological misfolding and aggregation of the protein called TDP-43 (TAR-DNA binding protein of 43kilodalton), within specific areas of the brain(1). LATE occurs with increasing frequency in persons beyond 85 years of age, reaching highest prevalence in the oldest old. Distinct from other neurodegenerative diseases such as Alzheimer's Disease and frontotemporal dementia (FTD), LATE still shares overlapping clinical and pathological features with other subtypes of disease that contribute to dementia. The primary distinction lies in the predominant protein pathology, and the localization of that pathology: whereas Alzheimer’s disease involves amyloid-beta plaques and tau protein tangles, and FTD is often linked to TDP-43 pathology that is very widespread in the brain, LATE is defined by TDP-43 deposited in a more restricted distribution.

Within the broader classification of neurodegenerative disorders, LATE is subcategorized under the umbrella of TDP-43 proteinopathies(5), which also include conditions like frontotemporal lobar degeneration (FTLD)/FTD and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) where TDP-43 was discovered as a pathological marker in the first place(6), indicating a common pathological protein despite distinct neuroanatomical and clinical findings. LATE primarily affects the medial temporal lobe regions, particularly the hippocampus and amygdala, which are crucial for memory functions. This localization correlates with clinical presentation as a predominantly amnestic (memory-impacting) condition, which is often mistaken for Alzheimer's disease(7).

LATE's classification is also nuanced by its high potential to coexist with other neuropathological conditions. Autopsy studies frequently reveal the coexistence of LATE neuropathologic changes (LATE-NC) with Alzheimer’s disease neuropathologic changes (ADNC) and other pathologies such as Lewy bodies and vascular brain injury. This overlap can complicate diagnosis and treatment, emphasizing the importance of accurate classification and understanding of its unique and intersecting features within the neurodegenerative disease spectrum. Understanding these relationships is crucial for developing targeted treatments and improving diagnostic accuracy for aging populations.

In terms of nomenclature, the acronym LATE stands for Limbic-predominant Age-related TDP-43 Encephalopathy: “limbic” is related to the brain areas first involved, “age-related” indicates that this is a disease that increases in the geriatric population(1), “TDP-43” indicates the aberrant mis-folded protein (or proteinopathy) deposits in the brain that characterize LATE, and “encephalopathy” means illness of brain. A connotation of the acronym “LATE” is that the designation refers to the onset of disease usually in persons aged 80 or older, i.e. late in the human aging spectrum.

For disease-specific diagnostic staging according to neuropathologic methods, see below (“Neuropathologic staging”).

For clinical diagnostic rubrics (e.g., clinically Probable or Possible LATE), see below (“Clinical diagnostic categories”).

Signs and Symptoms[edit]

LATE is associated with a range of clinical symptoms that primarily affect cognitive functions, particularly memory. The clinical manifestations of LATE closely mimic those of Alzheimer's disease, often leading to diagnostic challenges(3, 8). Here, we explore the key symptoms of LATE, their progression, and the impact on affected individuals.

Cognitive Symptoms:[edit]

- Memory Impairment: The hallmark symptom of LATE is a progressive memory loss that predominantly affects short-term and episodic memory(9, 10). This impairment is often severe enough to interfere with daily functioning and is usually remains the chief neurologic deficit, unlike other types of dementia in which non-memory cognitive domains and behavioral changes might be noted earlier or more prominently.

- “Pure LATE”: gradual Cognitive Decline: The amnestic syndrome in LATE tends to worsen gradually, leading to significant memory deficits over time(3). Unlike more rapidly progressive dementias, the cognitive decline in LATE, when it is the chief pathology present is typically slow.

- Severe symptoms and rapid deterioration when combined with Alzheimer’s disease. Approximately ½ of dementia in advanced age includes both Alzheimer’s and LATE pathologies, and these individuals are at risk for more swift and severe disease course(3).

- Dementia: This is a clinical syndrome, rather than a particular disease process – analogous to “shortness of breath”(dyspnea). Thus, many different diseases including LATE contribute to dementia. The implications of the term “dementia” are that there is cognitive impairment severe enough to impair activities of daily living such as feeding oneself.

Behavioral and Psychological Symptoms:

- Mood Changes and behavioral changes: Individuals with LATE may experience mood swings, depression, and apathy. These symptoms can complicate the clinical picture, especially in the elderly who may have other comorbid conditions affecting their mood and cognitive status. Neuropsychological disturbances are particularly common when LATE is combined with Alzheimer’s disease.

- There can be subtle changes in personality and behaviour. Family members may notice less social interaction, and a general withdrawal from previously enjoyed activities.

Development and Progression:[edit]

The symptoms of “Pure” LATE develop more insidiously than those of Alzheimer's disease. Initial symptoms are often so mild that they are dismissed as normal aging(1). However, as the disease progresses, memory impairment becomes more prominent and begins to interfere significantly with daily activities. The rate of progression varies widely among individuals but generally occurs over several years. Again, it should be emphasized that up to ½ of dementia in advanced age involves both Alzheimer’s and LATE pathologies, and affected individuals with so-called “mixed” pathologies have more rapid and severe disease course.

Impact on Patients:[edit]

- Daily Living and Functionality: Memory loss and cognitive decline significantly affect the ability to perform daily tasks independently and can lead to increased reliance on family members or caregivers.

- Quality of Life: The gradual loss of memory and other cognitive functions can severely impact the quality of life, leading to social withdrawal and isolation. LATE has also been associated with urinary incontinence(11).

- Caregiver Burden: The slow but progressive nature of the disease can place a substantial burden on caregivers necessitate long-term care and support.

Causes[edit]

Limbic-predominant Age-related TDP-43 Encephalopathy (LATE) is a neurodegenerative disorder affecting older adults, characterized by the abnormal accumulation of TDP-43 protein in the brain. The exact causes of LATE are not fully understood, but a combination of factors, particularly genetic risk factors, are believed to contribute to its development. Here we explore these factors based on current research and theories.

Genetic Factors:[edit]

- The major known risk factors for LATE-NC are genetic: variations in the TMEM106B, GRN, APOE, ABCC9, KCNMB2, and WWOX genes have been linked to altered risk for LATE-NC (and/or hippocampal sclerosis dementia)(12-16).

Environmental Factors:

- Age: The strongest known risk factor for LATE is advanced age. The prevalence of LATE increases significantly in individuals over 80 years old, and the average patient with LATE is ten years older than the average patient with Alzheimer’s disease, suggesting that aging-related biological processes—yet to be comprehensively identified (but which include TMEM106B c-terminal fragments which are deposited in an age-related manner)—play roles in the development of LATE.

- Brain trauma: Although brain trauma (either single or multiple/chronic traumatic impacts) can produce brain changes that are qualitatively different from LATE-NC, there may be interactions between brain trauma and LATE-NC mechanistically (17). Further, those with brain damage from trauma or other sources may have worse outcomes with a given burden of LATE-NC in the brain.

- Comorbid Pathologies: Many cases of LATE occur alongside other neurodegenerative diseases, such as Alzheimer’s disease. This co-occurrence may suggest shared or synergistic risk factors, genetic or environmental, that contribute to neurodegeneration.

Lifestyle Factors:[edit]

- Education and Cognitive Reserve: There is indication from broader dementia research that higher educational attainment and engaging in mentally stimulating activities might delay the onset of clinical symptoms in neurodegenerative diseases. Whether this directly affects the risk of developing LATE or just modifies its presentation is still under investigation.

- Brain Health and Lifestyle: While specific lifestyle factors directly causing LATE have not been definitively identified, general factors that affect brain health appear to influence risk of a given amount of pathology being correlated with cognitive impairment. Lifestyle factors include diet, physical activity, social and intellectual stimulation, cardiovascular health, and exposure to toxins.

Causal Mechanisms (and see Pathophysiology, below):[edit]

- Neuroinflammation: Chronic inflammation in the brain is a known factor in many neurodegenerative diseases and may also play a role in LATE. Inflammatory processes could contribute to or exacerbate TDP-43 pathology.

- Protein Homeostasis: Disruptions in protein homeostasis, which include protein synthesis, folding, trafficking, and degradation, are likely involved in LATE. An imbalance in these processes could lead to the accumulation of misfolded TDP-43, contributing to disease progression.

Pathophysiology[edit]

Limbic-predominant Age-related TDP-43 Encephalopathy (LATE) involves complex pathophysiological mechanisms characterized by the abnormal deposition of the TDP-43 protein in the brain's limbic structures.

Role of TDP-43 Protein:[edit]

- TDP-43 Protein Functions: TDP-43 (Transactive response DNA-binding protein 43) is a nuclear protein involved in regulating gene expression by modifying RNA. It plays critical roles in RNA processing, including splicing, stability, and transport. In healthy cells, TDP-43 is predominantly found in the nucleus(18, 19).

- Mislocalization and Aggregation: In LATE, TDP-43 protein abnormally accumulates in the cytoplasm of neurons and glial cells, forming aggregates. This mislocalization disrupts its normal nuclear functions and contributes to cellular dysfunction and neuronal death. The exact triggers of TDP-43 mislocalization and aggregation are not fully understood but are believed to involve both genetic predispositions and acquired factors(19-25).

- Spread and Toxicity: Studies suggest that TDP-43 pathology may propagate in a prion-like manner(26-28), spreading from neuron to neuron and thus contributing to the progressive nature of LATE. The presence of TDP-43 aggregates interferes with various cellular functions and may induce toxicity both through interference with normal TDP-43 function (loss of function) or through gain of new toxic functions(24, 29).

Neuropathological Observations, including Common Co-existing Pathologies:[edit]

· Staging of TDP-43 Pathology: LATE neuropathology is typically graded based on the extent and distribution of TDP-43 inclusions within the brain. Early stages may involve localized TDP-43 pathology in the amygdala, while more advanced stages involve the hippocampus, entorhinal cortex, and other medial temporal lobe structures(1, 30, 31). For more details on the pathological stages of LATE-NC, see “Pathologic Examination”, below.

- Hippocampal Sclerosis: Advanced LATE is often associated with hippocampal sclerosis, characterized by severe neuron loss and gliosis in the hippocampus(32, 33). This feature significantly contributes to the memory deficits observed in LATE.

- Brain arteriolosclerosis: LATE, often coexisting with hippocampal sclerosis, often coexists with a small blood vessel pathology affecting cerebral arterioles, which is termed arteriolosclerosis(34).

- Tauopathy: LATE is more common in cases with comorbid tauopathy, including ADNC, primary age-related tauopathy (PART), and age-related tau astrogliopathy (ARTAG)(35, 36).

Molecular Pathways:[edit]

- Interaction with Other Pathologies: LATE frequently coexists with other neurodegenerative pathologies, such as Alzheimer's disease neuropathologic changes (ADNC). The interplay between TDP-43 pathology and other pathologies like tau tangles and amyloid-beta plaques may exacerbate cognitive impairment.

- Genetic Influences: Certain genetic factors, such as mutations or polymorphisms in genes related to TDP-43 processing and function, may predispose individuals to develop LATE. These genetic elements can affect the stability, aggregation propensity, or cellular trafficking of TDP-43. For example, the APOE e4 allele that confers increased risk for ADNC also increases risk of LATE-NC; further, FTLD risk genes TMEM106B and GRN/progranulin are also implicated in risk of LATE-NC.

Cellular and Systemic Impact:[edit]

- Neuronal Dysfunction and Loss: The aggregation of TDP-43 in the cytoplasm likely disrupts normal neuronal function by impairing RNA and protein homeostasis(24). This disruption can lead to synaptic dysfunction and eventual neuronal death, which are critical contributors to the clinical symptoms of LATE.

- Inflammatory Responses: There is evidence suggesting that TDP-43 aggregates may trigger inflammatory responses in the brain, and the opposite (inflammationàTDP-43 pathology) also may be true. Chronic neuroinflammation is known to exacerbate neurodegeneration and may play a significant role in the progression of LATE. TDP-43 pathology has also been shown to be increased in some inflammatory neurological conditions such as subacute sclerosing panencephalitis, which is caused by a virus (37).

Diagnosis[edit]

The diagnosis of LATE is challenging because its symptoms overlap with those of other types of dementia, especially Alzheimer’s disease. At present LATE is primarily diagnosed posthumously, through neuropathological examination. However, ongoing research aims to refine the antemortem diagnostic criteria and methods. The current approach to diagnosing LATE in living patients involves a combination of clinical evaluation, neuroimaging, and biomarker analysis, as detailed below.

Clinical Evaluation:[edit]

- Medical History and Symptoms: Detailed patient history focusing on age at onset and nature and rate of decline of cognitive functions, particularly memory loss, is critical. Clinicians also assess other cognitive domains and inquire about any changes in behavior or personality that might indicate broader neurological impact.

- Neurological Examinations: Neuropsychologic examinations include testing to assess memory, executive function, language abilities, and other cognitive functions. These tests help differentiate LATE from other neurodegenerative diseases based on the presence of primarily amnestic versus multi-domain cognitive impairments.

Imaging Studies:[edit]

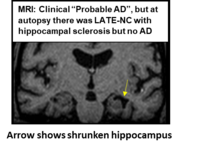

- Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI): MRI scans are used to observe structural changes in the brain. In LATE, MRI may reveal severe atrophy in the medial temporal lobe, particularly in the hippocampus and amygdala, which are key areas affected by TDP-43 pathology, and may indicate hippocampal sclerosis.

- Positron Emission Tomography (PET): While PET scans are commonly used to detect amyloid and tau pathologies in Alzheimer’s disease, the absence of marked aberration in these may support the diagnosis of LATE by ruling out significant amyloid or tau burdens indicative of Altzheimer’s disease.

Biomarker Analysis:[edit]

- Cerebrospinal Fluid (CSF) and Blood Biomarkers: Biomarkers for neuronal damage such as tau protein and neurofilaments can be measured in the cerebrospinal fluid and blood. A lack of amyloid-beta and tau relative to the degree of cognitive impairment may suggest LATE, if typical Alzheimer’s pathology is not present.

- Vigorous efforts are ongoing to identify specific biomarkers for TDP-43 pathology. These include potential CSF markers or blood-based biomarkers derived from advanced protein assays, which could specifically indicate the presence of abnormal TDP-43.

Clinical diagnostic categories:

· In terms of clinical classification, LATE is characterized by progressive decline in memory and cognitive functions, and can coexist with other forms of dementia. More specifically, there is a core clinical LATE syndrome characterized by progressive episodic memory loss and substantial hippocampal atrophy. Further, clinical criteria are laid out for Possible LATE (when Ab amyloid biomarkers are unavailable), Probable LATE (neurodegeneration lacking Ab amyloid biomarker positivity, where LATE-NC may be considered primary driver of impairment), and Possible LATE with AD (Ab amyloid positivity but neurodegeneration out of proportion to that expected with pure ADNC).

Pathological Examination (Gold standard for disease presence and severity):[edit]

- Autopsy and Histopathological Analysis: Definitive diagnosis of LATE currently relies on post-mortem examination, where brain tissues are examined for specific patterns of TDP-43 proteinopathy. The distribution and severity of TDP-43 inclusions, especially in the amygdala and hippocampus, confirm the presence of LATE.

· Staging of TDP-43 Pathology: The specific severity/extent of LATE-NC follows on the basic staging scheme of Keith Josephs and colleagues (30) and is staged along a 0-3 staging scheme(1, 38): when TDP-43 pathology is only seen in the amygdala, that is Stage 1; when TDP-43 pathology is in the amygdala and hippocampus, that is LATE-NC Stage 2; and, when TDP-43 pathology is in amygdala, hippocampus, and middle frontal gyrus, that is LATE-NC Stage 3.

Diagnostic Challenges:[edit]

- Overlap with Other Dementias: LATE often coexists with Alzheimer’s disease and other dementias, making it difficult to diagnose based solely on clinical and imaging findings.

- Lack of Specific Antemortem Tests: There are currently no definitive antemortem tests specifically for TDP-43, although this is an active area of research.

Prognosis[edit]

The prognosis of LATE varies significantly depending on several factors including the age at onset, stage of the disease at diagnosis, the presence and degree of cerebrovascular disease and of other comorbidities, and individual patient factors. Understanding the progression, expected outcomes, and influencing factors is crucial for managing LATE effectively and providing appropriate care and support to affected individuals and their families.

Progression of LATE:[edit]

- Gradual Cognitive Decline: LATE typically manifests as a slow, progressive decline in memory and other cognitive functions, which distinguishes it from more rapidly progressing forms of dementia(3). The rate of progression can vary widely among individuals.

- Stage-Dependent Symptoms: Early stages may involve subtle memory impairments that gradually worsen. As LATE progresses, patients may experience more significant memory loss and eventually exhibit symptoms affecting other cognitive domains, although the primary impairment usually remains in memory.

Expected Outcomes:[edit]

- Increasing Dependency: Progression to severe dementia is common, and as with many forms of dementia, individuals with LATE gradually require more assistance with daily activities, leading to significant dependency on caregivers.

- Impact on Quality of Life: The gradual loss of independence and cognitive function significantly affect the quality of life of patients and their families. Emotional and psychological support is often necessary as part of the care regimen.

Factors Influencing Prognosis:[edit]

- Age at Onset: The age at which symptoms begin can influence the rate of progression: when symptoms start later in life progression is typically slower.

- Genetic Factors: Genetics can influence the severity and progression of LATE, certain genetic variants leading to earlier onset or faster progression.

- Comorbidities: While LATE alone usually progresses slowly, the concurrent presence of other neurodegenerative diseases such as Alzheimer's disease or cerebrovascular disorders is associated with more rapid clinical progression, with more cognitive and non-cognitive domains possibly being affected, e.g. urinary incontinence and motor (specifically respiratory muscle weakness) (11, 39).

- Overall Health and Lifestyle: General health and lifestyle factors, including diet, exercise, cardiovascular health, social contact, and management of other chronic conditions, can substantially influence the progression of cognitive decline in LATE.

Epidemiology[edit]

LATE is an increasingly recognized neurodegenerative condition that affects the elderly population and the prevalence is highest in the “oldest-old” (beyond age 90years)(1, 3, 40).

Prevalence and Incidence:[edit]

- Prevalence: LATE is estimated to affect a significant portion of the elderly population, especially those over the age of 80. Studies suggest that LATE neuropathological changes are present in >30% of individuals older than 85 years, making it one of the more common neurodegenerative conditions in the elderly(40-42). LATE often coexists with other pathologies such as Alzheimer's disease and/or cerebrovascular disorders.

- Incidence: Specific incidence rates for LATE are challenging to determine due to the overlap of its clinical presentation with other types of dementia, the paucity of population-based studies, potential variations by ethnic group, and—as reliable biomarkers for LATE have not yet been identified-- the fact that definitive diagnosis is still possible only through autopsy.

Demographic Information:[edit]

- Age: The risk of developing LATE increases with age, being rare in individuals under 65 and increasingly common in those over 80.

- Sex: Studies have not shown consistent differences between males and females in the prevalence of LATE.

- Ethnic and Racial Groups: Limited data are available on the prevalence of LATE across different ethnic and racial groups. Initial studies have not indicated significant differences in prevalence based on race or ethnicity(43, 44).

Geographic Distribution:[edit]

- Global Distribution: LATE has been identified in populations studied around the world. However, differences in study designs, diagnostic criteria, and awareness of the disease may affect reported rates from different countries.

- Influence of Health Systems: The recognition and reporting of LATE may also vary significantly depending on the local healthcare system's capacity to diagnose and record cases of dementia, particularly in settings where detailed neuropathological examinations are less common.

Risk Factors:[edit]

- Genetic Factors: Certain genetic markers have been associated with an increased risk of LATE, but the overall genetic contribution to risk is complex and multifactorial.

- Comorbidities: The presence of other neurodegenerative or cerebrovascular diseases can influence the recognition and clinical course of LATE.

Implications for Public Health:[edit]

- Underdiagnosis: LATE is undoubtedly underdiagnosed during life, as it has only relatively recently been defined as an entity, cannot be diagnosed with certainty during life, and its symptoms overlap with those of a more widely recognized condition, Alzheimer's disease.

- Impact on Healthcare: Understanding the true epidemiological impact of LATE is essential for planning of research, healthcare, and resource allocation, especially as populations age.

History[edit]

LATE is a relatively recently recognized neurological disorder, characterized by the pathological aggregation of TDP-43 protein predominantly affecting the limbic structures critical for memory and cognition. The historical context of LATE, from its discovery to the evolution of our understanding, sheds light on the complexities of diagnosing and studying age-related dementias.

Discovery and Initial Observations:[edit]

· Initial Observations: The pathological signatures of the disorder now known as LATE have been observed for some time, but focused attention to its distinguishing pathologic features and on the TDP-43 protein that is part of its mechanism have been relatively recent. TDP-43 was first linked to neurodegeneration in 2006, primarily in association with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) and frontotemporal lobar degeneration (FTLD)(6).

· Recognition as a Distinct Entity: It was not until the late 2000s and early 2010s that researchers began to recognize a pattern of TDP-43 pathology that was distinct from ALS and FTLD in elderly individuals, often co-existing with but distinct from Alzheimer's disease pathology(45-48).

Formation of a Consensus:[edit]

- 2019 Consensus Report: A milestone in the history of LATE was the publication of a consensus report in 2019 by a group of international experts(1). This report formally recognized LATE as a distinct disease entity, described its neuropathological criteria, and established its clinical relevance. This consensus was crucial for distinguishing LATE from other memory disorders of aging, and from other TDP-43 proteinopathies, as required for raising awareness among clinicians and researchers. There has been some debate and discussion as to optimal nomenclature for this condition(49, 50).

Evolution of Understanding:[edit]

- Differentiation from Alzheimer’s Disease: Initially, many cases of LATE were and are diagnosed as Alzheimer’s disease due to overlapping symptoms, such as memory loss. As research progressed, it became clear that LATE often occurred in the absence of significant Alzheimer’s pathology, prompting a re-evaluation of past cases and diagnoses.

- Pathophysiological Insights: Over time, studies began to unravel the unique pathophysiological mechanisms of LATE, particularly how TDP-43 abnormalities contribute to neurodegeneration. The recognition that TDP-43 pathology follows a predictable pattern within the brain helped refine diagnostic and staging criteria.

- Impact of Aging: Researchers have also focused on understanding how aging influences TDP-43 pathology, with LATE providing a model for studying age-related cellular and molecular changes in the brain.

Society and Culture[edit]

The frequent presence of LATE in dementia of aging that has a different underlying mechanism from Alzheimer’s disease has important implications for research and for patients, families, and healthcare systems. This section explores the social and cultural impact of LATE, including its effects on individuals' lives, the burden on caregivers, economic considerations, and quality of life considerations.

Impact on Patients:[edit]

- Cognitive Decline: LATE leads to progressive cognitive decline, primarily affecting memory and other cognitive functions critical for daily activities and independence. As the disease advances, patients may experience difficulties in communication, decision-making, and maintaining relationships.

- Emotional and Psychological Effects: The cognitive decline associated with LATE can lead to feelings of frustration, confusion, and depression in patients. Coping with the loss of cognitive abilities and the awareness of declining health can significantly impact emotional well-being in patients and families.

Burden on Caregivers:[edit]

- Increased Care Needs: As LATE progresses, patients require increasing levels of assistance with daily activities, leading to significant caregiving responsibilities for family members or professional caregivers.

- Emotional and Financial Strain: Caregivers often experience high levels of stress, anxiety, and depression due to the demands of caring for someone with LATE. Additionally, caregiving duties may impact caregivers' ability to work outside the home, leading to financial strain.

Impact on Healthcare Systems:[edit]

- Diagnostic Challenges: LATE presents diagnostic challenges due to the overlap of its symptoms with other neurodegenerative diseases such as Alzheimer's disease. This can result in delayed or incorrect diagnoses, leading to suboptimal management and increased healthcare costs(4).

- Resource Allocation: The increasing prevalence of LATE, coupled with the chronic nature of the disease and the need for long-term care, places a strain on healthcare resources, including hospitals, clinics, and long-term care facilities.

Economic Considerations:[edit]

- Direct Medical Costs: The direct medical costs associated with LATE include diagnostic tests, medications, physician visits, and long-term care services. These costs can be substantial, especially in later stages of the disease when patients require more intensive care.

- Indirect Costs: Indirect costs, such as lost productivity due to caregiving duties or early retirement, also contribute to the economic burden of LATE on individuals, families, and society as a whole.

Quality of Life Considerations:[edit]

- Loss of Independence: The progressive nature of LATE often results in a loss of independence for patients, impacting their quality of life. Maintaining autonomy and dignity becomes increasingly challenging as the disease advances.

- Social Isolation: Social interactions may become limited as cognitive decline progresses, leading to feelings of loneliness and isolation for patients. Support networks and community resources play a crucial role in maintaining social connections and overall well-being.

Cultural Perspectives:[edit]

- Stigma and Misunderstanding: Stigma surrounding dementia and cognitive decline may lead to social isolation and discrimination against individuals with LATE and their families. Cultural attitudes towards aging and cognitive impairment can influence how LATE is perceived and addressed within communities.

- Advocacy and Awareness: Advocacy organizations and community initiatives play a vital role in raising awareness about LATE, reducing stigma, and advocating for better support and resources for patients and caregivers.

References[edit]

Further reading[edit]

- "Guidelines proposed for newly defined Alzheimer's-like brain disorder". National Institute on Aging. National Institute of Health. 30 April 2019. Retrieved 30 April 2019.