Alas! and Did My Saviour Bleed

| Alas! and Did My Saviour Bleed | |

|---|---|

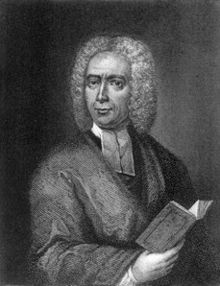

| by Isaac Watts | |

Isaac Watts | |

| Genre | Hymn |

| Meter | 8.6.8.6 |

| Melody | "Martyrdom" (Hugh Wilson), "Hudson" (Ralph E. Hudson) |

| Published | 1707 |

"Alas! and Did My Saviour Bleed" is a hymn by Isaac Watts, first published in 1707.

History[edit]

The hymn was first published in 1707, in Isaac Watts's three-volume collection Hymns and Spiritual Songs. It was included in volume 2, which comprised songs "Composed on Divine Subjects",[1] and was given the heading "Godly sorrow arising from the Sufferings of Christ."[2]

In the Canterbury Dictionary of Hymnology, Alan Gaunt describes it as "one of Watts's most intense lyric poems," which "emphasises the emotional effect on the writer and the reader/singer."[3]

According to Leland Ryken, the hymn contains the "speaker's thought process as he comes to grips with the crucifixion and what it means for him", and invites the singer to "enact the same thought process."[4]

Comparing this hymn with another well-known Isaac Watts hymn, "When I Survey the Wondrous Cross", Carl P. Daw Jr. notes that where the latter is "objective and sweeping; this one is subjective and tightly focused."[5]

The traditional words have commonly been paired with the hymn tune Martyrdom,[6] which is an adaptation of a traditional Scottish melody, attributed to Hugh Wilson.[7]

It has been more popular in the USA and Canada than in the UK; in North America, it is one of the most-sung hymns by Isaac Watts.[3]

Text[edit]

Original words[edit]

The original hymn had six four-line stanzas. The opening verses offer a concise summary of the doctrine of penal substitution.[8]

Alas! and did my Saviour bleed,

And did my sov’reign die?

Would he devote that sacred Head

For such a Worm as I?

Thy Body slain, sweet Jesus, thine,

And bath’d in its own Blood,

While all expos’d to Wrath divine

The glorious Sufferer stood?

Was it for Crimes that I had done

He groan’d upon the Tree?

Amazing Pity! Grace unknown!

And Love beyond Degree?

Well might the Sun in Darkness hide,

And shut his Glories in,

When God the mighty Maker died

For Man the Creatures Sin.

Thus might I hide my blushing Face

While his dear Cross appears,

Dissolve my Heart in Thankfulness,

And melt mine Eyes to Tears.

But Drops of Grief can ne’er repay

The Debt of Love I owe;

Here, Lord, I give my self away,

’Tis all that I can do.[3]

Alterations[edit]

Hymn books commonly omit the second stanza,[3] which is described as an optional verse in the originally published version.[2] In Salvation Army hymn books, the line "God the mighty Maker" in stanza four is changed to "Christ the mighty maker."[3]

Choruses[edit]

In the context of late 19th-century revivalism, a number of traditional hymns were turned into gospel hymns with the addition of a chorus.[9][10] 1885, hymnwriter Ralph E. Hudson added a chorus in his hymnbook Songs of Peace, Love, and Joy, to be repeated after each verse.[1][11] The words and music of this refrain probably originated in camp meetings of the time.[7][12][13]

At the cross, at the cross,

Where I first saw the light,

And the burden of my heart rolled away,

It was there by faith I received my sight,

And now I am happy all the day!

When this chorus is included, the hymn is often known as "At the Cross."[14] Hudson also wrote a new tune in a gospel style for the verses; this tune is known as Hudson.[1][7]

Other hymn books have added a chorus to the hymn. Charles Price Jones, founder of the Church of Christ (Holiness) U.S.A., added the following refrain:

I surrendered at the cross,

and my heart was cleansed from sin

By the precious blood the Savior shed for me;

I am living in His word, and it daily keeps me clean!

Hallelujah, from the pow'r of sin I'm freed.[9]

In the 1986 Song Book of the Salvation Army, the added refrain was:

Remember me, remember me,

O Lord, remember me;

Remember, Lord, thy dying groans,

And then remember me.[3]

Worm Theology[edit]

This hymn has been criticised as an example of "worm theology", which suggests to people that "low self-worth means God is more likely to show mercy and compassion upon them."[15] Writing for Christianity Today, Mark Galli found the line problematic for promoting the idea that "only by abasing ourselves are we able to grasp and receive God's mercy."[16] Theologian Anthony A. Hoekema has described it as an example of a hymn that has made a "contribution to the negative self-image often found among Christians."[17]

In several hymnals, the word "worm" in the first stanza is change to "one"[3] or more commonly, the line is altered to "sinners such as I".[7][14] David W. Music has defended the use of the word "worm", noting its parallels in the Bible and its function in the song as a whole:[18]

Here, the "worm" language sets up a contrast between the majestic "Sacred Head" of Christ and the hymn writer’s (and singer’s) own status as a creature that falls far short of the glory of God. The writer may have also had in mind Job 25:6 ("How much less man, that is a worm? and the son of man, which is a worm?") or Psalm 22:6 ("But I am a worm, and no man").

Theologian Marva Dawn argued that the hymn's "worm" imagery is an important way of highlighting the "incredible freedom and immense joy of forgiveness."[19] Hymnologist Madeleine Forell Marshall suggested Watts was not intending to make a general comment on humanity, but to describe how, when faced with the death of Jesus, we are "initially filled with powerful disgust and graphic self-loathing."[20]

References[edit]

- ^ a b c The New Century Hymnal Companion: A Guide to the Hymns. Pilgrim Press. 1997. p. 311. ISBN 9780829812077.

- ^ a b John, Julian (1907). A Dictionary of Hymnology. John Murray. p. 34.

- ^ a b c d e f g Gaunt, Alan. "Alas! and did my Saviour bleed". The Canterbury Dictionary of Hymnology. Canterbury Press.

- ^ Ryken, Leland (2020). 40 Favorite Hymns for the Christian Year. P&R Publishing. p. 47. ISBN 9781629957951.

- ^ Daw, Carl P. (2016). Glory to God: A Companion. Westminster John Knox Press. p. 214. ISBN 9780664503123.

- ^ "Alas, and did my saviour bleed". Hymnary.org. Retrieved 6 May 2024.

- ^ a b c d Reynolds, William Jensen (1976). Companion to Baptist Hymnal. Broadman Press. pp. 27–29.

- ^ Stackhouse, Rochelle (2019). "Isaac Watts: Composer of Psalms and Hymns". In Lamport, Mark A. (ed.). Hymns and Hymnody: Historical and Theological Introductions, Volume 2. Wipf and Stock. p. 204.

- ^ a b Spencer, Jon Michael (1992). Black Hymnody: A Hymnological History of the African-American Church. University of Tennessee Press. pp. 106–107. ISBN 9780870497605.

- ^ Peeler, Lance J. (2012). "Gospel Hymn". Continuum Encyclopedia of Popular Music of the World, Volume 8. Bloomsbury Academic. p. 231.

- ^ Lemke, Steve (2014). "Worship Wars: Theological Perspectives on Hymnody Among Early Evangelical Christians". Journal of the Grace Evangelical Society. 27 (52): 69.

- ^ Young, Carlton (1993). Companion to the United Methodist Hymnal. Abingdon Press. p. 188.

- ^ Hustad, Don (1978). Dictionary-Handbook to Hymns for the Living Church. Hope Publishing. p. 103.

- ^ a b Hobbs, June Haddon (1997). I Sing for I Cannot Be Silent: The Feminization of American Hymnody, 1870–1920. University of Pittsburgh Press. pp. 4–5. ISBN 9780822974963.

- ^ Coughlin, Paul (2008). No More Jellyfish, Chickens or Wimps: Raising Secure, Assertive Kids in a Tough World. Baker. p. 101.

- ^ Galli, Mark (1 April 2010). "Asking the Right Question". Christianity Today.

- ^ Hoekema, Anthony A. (1975). The Christian Looks at Himself. Eerdmans. p. 17.

- ^ Music, David W. (2020). Repeat the Sounding Joy: Reflections on Hymns by Isaac Watts. Mercer University Press. p. 25. ISBN 9780881467697.

- ^ Dawn, Marva J. (1995). Reaching Out Without Dumbing Down: A Theology of Worship for This Urgent Time. Eerdmans. p. 90.

- ^ Marshall, Madeleine Forell (1995). Common Hymnsense. GIA Publications. p. 31. ISBN 9780941050692.