DETCOM Program

The DETCOM Program (also "Det-Com," "Detcom"), along with the COMSAB (or "COMmunist SABotage"[1]) Program formed part of the "Emergency Detention Program" (1946–1950) of Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI).[2][3] As FBI historian Athan Theoharis described in 1978, "The FBI compiled other lists in addition to the Security Index. These include a "Comsab program" (concentrating on Communists with a potential for sabotage), and "Detcom program" (a "priority" list of individuals to be arrested), and a Communist Index (individuals about whom investigation did not "reflect sufficient disloyal information" but whom the bureau deemed to be 'of interest ... '.")[4]

Secrecy[edit]

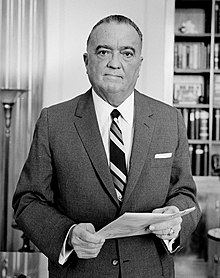

Long-time FBI head J. Edgar Hoover wanted the program to remain secret from the public:

He thus instructed his top agents that "no mention must be made in any investigative report relating to the classifications of top functionaries and key figures, nor to the Detcom or Consab Program, nor to the Security Index or the Communist Index. These investigative procedures and administrative aids are confidential and should not be known to any outside agency."[5]

Description[edit]

Most sources take "DETCOM" to stand for "DETain [as] COMmunist" (bolding added):

- 1976 -Select Committee to Study Governmental Operations, United States Senate: "The Emergency Detention Program, 1946-1950": The development of plans during this period for emergency detention of dangerous persons and for intelligence about such persons took place entirely within the executive branch. In contrast to the employee security program, these plans were not only withheld from the public and Congress but were framed in terms which disregarded the legislation enacted by Congress. Director Hoover's decision to ignore Attorney General Biddle's 1943 directive abolishing the wartime Custodial Detention List had been an example of the inability of the Attorney General to control domestic intelligence operations. In the 1950s the FBI and the Justice Department collaborated in a decision to disregard the attempt by Congress to provide statutory direction for the Emergency Detention Program. This is not to say that the Justice Department itself was fully aware of the FBI's activities in this area. The FBI kept secret from the Department its most sweeping list of potentially dangerous persons, first called the "Communist Index" and later renamed the "Reserve Index," as well as its targeting programs for intensive investigation of "key figures" and "top functionaries" and its own detention priorities labeled "Detcom" and "Comsab".

- 1995 – M. Wesley Swearingen wrote: DETCOM was part of J. Edgar Hoover's (in)famous Security Index. "I became very knowledgeable about the Security Index, because all my subjects were tagged either DETCOM ("detain as communist") or COMSAB. COMSAB was the designation for someone who had a job in a company with government contractss, and who therefore had an opportunity to commit sabotage in the event of a national emergency. Subjects tagged COMSAB were to be arrested first, then those tagged DETCOM, followed by all others on the Security Index. After all the individuals on the Security Index were arrested, those on the Communist Index, later called the Reserve Index, were to be arrested."[6]

- 2003 – Fred Jerome wrote: "In the early 1950s, congressional committees were keenly interested in hearing how many hard-core communists Hoover was prepared to put into "detention camps" in case of a war with Russia. This was the "Detention of Communists"–or Det-Com–lst. While the FBI had millions of security files, "only" several thousand were slated for such emergency camps. The purpose of Det-Com, David Wise explains, was simply "to determine which of us to lock up in the event of war or a presidentially decreed 'emergency'." On September 7, 1950 (the day G-2's first Einstein spy-memo arrived), Hoover told the senators the FBI had targeted twelve thousand Reds to be rounded up "in the event of war with Russia." The Washington Post reported the next day that he also requested funding for 835 new agents and 1,218 new clerical workers ... How many people were actually in Hoover's Det-com file? It wasn't a small number. Former FBI official Neil Welch says there were 'thousands'."[7]

- 2015 – Meredith Owen wrote: "The "detention of Communists" program, or DETCOM, tracked potential subversives and established a "Master Arrest Warrant" that would have made arrests easier if they became necessary, though over the course of the several decades that the FBI continued the program, the warrant was never used. The list included thirty-six Chinese aliens, a tiny fraction of the population, but enough to raise questions about Chinese residents' loyalties.[8]

List[edit]

By 1951, the FBI had formalized the program: "Forms beginning in 1951 included a space labeled "Tab for Detcom" and "Tab for Comsab."[9] ("Tab: To place in a special category in an FBI list such as Security Index, e.g., to tab an SI subject "Detcom."[10]) People listed on DETCOM were referred to as "tabbed for DETCOM."[11]

Americans "tabbed for DETCOM Program" included:

- (* means also on COMSAB Program list)

- George Richard Andersen (attorney for the International Longshoremen's and Warehousemen's Union or ILWU and its president Harry Bridges[12]

- Vincent Raymond Dunne [13]

- Franklin Folsom[14]

- Richard Gladstein (attorney for the International Longshoremen's and Warehousemen's Union or ILWU and its president Harry Bridges[12]

- Oskar Maria Graf[15]

- Duncan Chaplin Lee * [16]

- Malcolm X * [1][17]

- U.S. Representative Vito Marcantonio[18]

- George Oppen[19]

- Ronald Radosh[20]

- John F. Shelley

- Morton Sobell[21]

- Helen Sobell[21]

- Elaine Black Yoneda[22]

- Elijah Muhammad[23]

See also[edit]

References[edit]

- ^ a b Newton, Michael (16 January 2012). The FBI Encyclopedia. McFarland. p. 380. ISBN 9781476604176. Retrieved 4 October 2017.

- ^ Select Committee to Study Governmental Operations, United States Senate (23 April 1976). Supplementary Detailed Staff Reports on Intelligence Activities, Book III, Final Report (PDF). US GPO. p. 436. Retrieved 4 October 2017.

- ^ Select Committee to Study Governmental Operations, United States Senate (23 April 1976). Supplementary Detailed Staff Reports on Intelligence Activities, Book III, Final Report. US GPO. pp. 441, 446, 447. Retrieved 4 October 2017.

- ^ Theoharis, Athan (1978). Spying on Americans: Political Surveillance from Hoover to the Huston Plan. Temple University Press. pp. 48. ISBN 9780877221418. Retrieved 4 October 2017.

- ^ Keller, William W. (14 July 2014). The Liberals and J. Edgar Hoover: Rise and Fall of a Domestic Intelligence State. Princeton University Press. p. 63. ISBN 9781400859887. Retrieved 4 October 2017.

- ^ Swearingen, M. Wesley (1995). FBI Secrets: An Agent Exposé. South End Press. pp. 26, 40 (definition), 62. ISBN 9780896085015. Retrieved 4 October 2017.

- ^ Jerome, Fred (17 June 2003). The Einstein File: J. Edgar Hoover's Secret War Against the World's Most Famous Scientist. Macmillan. p. 197. ISBN 9780312316099. Retrieved 4 October 2017.

- ^ Owen, Meredith (27 October 2015). The Diplomacy of Migration: Transnational Lives and the Making of U.S.-Chinese Relations in the Cold War. Cornell University Press. p. 107. ISBN 9781501701467. Retrieved 4 October 2017.

- ^ American Friends Service Committee: Program on Government Surveillance and Citizens' Rights (1978). J. Edgar Hoover's Detention Plan: The Politics of Repression in the United States, 1939-1976. American Friends Service Committee. pp. 6, 13 (forms). Retrieved 4 October 2017.

- ^ Buitrago, Ann Mari; Immerman, Leon Andrew (1981). Are you now or have you ever been in the FBI files?: How to secure and interpret your FBI files. Grove Press. pp. 71, 173 ("tab"). ISBN 9780739195611. Retrieved 4 October 2017.

- ^

"Volume 5, Issue 1". CounterSpy. 1981: 37. Retrieved 4 October 2017.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ a b Wark, Colin; Galliher, John F. (23 April 2015). Progressive Lawyers under Siege: Moral Panic during the McCarthy Years. Lexington Books. pp. 4 (Gladstein), 192–195 (Andersen). ISBN 9780739195611. Retrieved 4 October 2017.

- ^ Haverty-Stacke, Donna T. (8 January 2016). Trotskyists on Trial: Free Speech and Political Persecution Since the Age of FDR. New York University Press. pp. 205, 270 (fn38 DETCOM). ISBN 9781479851942. Retrieved 4 October 2017.

- ^ Folsom, Franklin (1 January 1994). Days of Anger, Days of Hope: A Memoir of the League of American Writers, 1937-1942. University of Colorado Press. p. 134. ISBN 9780870813320. Retrieved 4 October 2017.

- ^ Stefan, Alexander (2000). "Communazis": FBI Surveillance of German Emigré Writers. Yale University Press. p. 192. ISBN 0300082029. Retrieved 4 October 2017.

- ^ Bradley, Mark A. (29 April 2014). A Very Principled Boy: The Life of Duncan Lee, Red Spy and Cold Warrior. Basic Books. p. 211. ISBN 9780465036653. Retrieved 4 October 2017.

- ^ Evanzz, Karl (10 January 2013). The Judas Factor: The Plot to Kill Malcolm X. Lulu Press. ISBN 9780977911233. Retrieved 4 October 2017.

- ^ Theoharis, Athan (1982). Beyond the Hiss Case: The Fbi, Congress, and the Cold War. Temple University Press. pp. 193. ISBN 9780877222415. Retrieved 4 October 2017.

- ^ Oppen, George (1990). The Selected Letters of George Oppen. Duke University Press. pp. 367 (fn43). ISBN 0822310244. Retrieved 4 October 2017.

- ^ Radosh, Ronald (1 January 2001). Commies: A Journey Through the Old Left, the New Left and the Leftover Left. Read How You Want. p. 55. ISBN 9781893554054. Retrieved 4 October 2017.

- ^ a b Deery, Phillip (3 October 2017). "Love, Betrayal, and the Cold War: An American Story" (PDF). American Communist History. 16 (1–2): 65–87. doi:10.1080/14743892.2017.1360630. S2CID 166191334.

- ^ Raineri, Vivian McGuckin (1991). The Red Angel: The Life and Times of Elaine Black Yoneda. International Publishers. p. 264. ISBN 9780717806867. Retrieved 4 October 2017.

- ^ Hoover, John Edgar (Feb 18, 1957). "Elijah Poole Internal Security - MCI" (FOIA scan of confidential inter-agency memo). FBI Records: The Vault. FBI.gov. p. 99. Retrieved Mar 21, 2018.