Matthew Beovich

The Most Reverend Matthew Beovich | |

|---|---|

| Archbishop of Adelaide | |

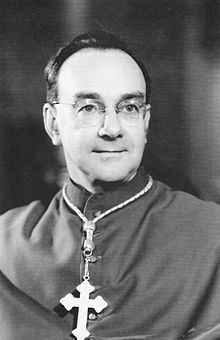

Beovich in 1950 | |

| Archdiocese | Adelaide |

| Installed | 7 April 1940 |

| Term ended | 1 May 1971 |

| Predecessor | Andrew Killian |

| Successor | James William Gleeson |

| Orders | |

| Ordination | 23 December 1922 |

| Consecration | 7 April 1940 |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 1 April 1896 |

| Died | 24 October 1981 (aged 85) Adelaide, Australia |

| Nationality | Australian |

Matthew Beovich (1 April 1896 - 24 October 1981) was an Australian Roman Catholic clergyman, and the fifth[1] Archbishop of Adelaide.

Early life[edit]

Matthew Beovich was born on 1 April 1896 in Carlton, a suburb of Melbourne, Victoria.[2] Matthew was the second of the four children of Mate (or Matta) Beovich, a fruiterer born in Croatia, and Elizabeth, née Kenny, who was born in Bendigo, Victoria.[2][3] He began his schooling at St George's School, Carlton before moving on to St. Joseph's Christian Brothers' College, North Melbourne as a full-time student between 1909 and 1912 when he passed the Senior Public Service examination. His contemporaries at the same school were Nick McKenna and Arthur Calwell, with whom he remained friends his whole life.[4] From 1912 until 1917, Beovich worked as a clerk in the Melbourne General Post Office, studying part-time and matriculating in 1913.[5] He was to return to his old school on many occasions whenever his business brought him to Melbourne.

In August 1917, Beovich left Melbourne for Rome to study for the priesthood.[6] For the next four years, he attended the Pontifical Urban College of Propaganda, receiving prizes in physics, church history and sacramental theology.[7] His thesis for his Doctorate of Divinity was a defence of the Catholic sacrament of confession.[8] On 6 August 1922 Beovich was ordained as a deacon,[9] and on 22 December that same year he was ordained a priest in the Basilica of St. John Lateran.[10] After exploring Europe, he returned to Melbourne in October 1923.[11]

Upon his return to Australia, Beovich briefly served as an assistant priest of a parish in North Fitzroy, in what would be his only experience of suburban parochial life.[12] In May 1924, he was appointed Director of Religious Instruction for the Archdiocese of Melbourne,[12] and over the next decade, the Archbishop of Melbourne Daniel Mannix gradually delegated all diocesan educational matters to Beovich.[13] In 1932, the Catholic Education Office was established with Mannix as director and Beovich as deputy director.[13] At some point in the next four years, Beovich was elevated to director, a reflection of Mannix's limited direct involvement in the organisation.[13] Until his installation as Archbishop of Adelaide in 1940, Beovich played an important role in Victorian Catholic education, sitting on the Council of Public Education (which oversaw non-government education and advised the minister of education) from 1932,[14] and authoring a new catechism for school children.[15] In 1940, Mannix told the Adelaide clergy that Beovich had "brought about a revolution in the Catholic schools of Melbourne."[16]

In 1925, Mannix appointed Beovich to the position of secretary of the Australian Catholic Truth Society.[17] He resigned this position in 1933, with Mannix citing as the reason the increased workload from his work in Catholic education and duties as the presenter of The Catholic Hour, a weekly radio programme on Melbourne station 3AW.[18]

Episcopacy[edit]

Consecration and early episcopacy[edit]

On 13 December 1939 Beovich received a phone-call from the Australian apostolic delegate informing him that he had been appointed by Pope Pius XII to be installed as the new archbishop of Adelaide, replacing Andrew Killian, who had died in June of that year.[19] In fact, Beovich had been contacted by the editor of the Advocate (a Melbourne Catholic newspaper) to comment on his appointment the night before, the confusion arising from the fact that the plane carrying the papal bull of appointment had crashed into the sea near Java. The mailbag was eventually recovered, and Beovich received the barely readable document in March 1940.[19]

Matthew Beovich was consecrated and installed as Archbishop of Adelaide in St. Francis Xavier's Cathedral, Adelaide, on 7 April 1940,[20] becoming the Archdiocese's first Australian-born bishop.[21][22] The cathedral was crowded for the consecration, with loudspeakers so those who could not fit inside could still hear the proceedings.[20] In addition, the entire ceremony was broadcast on radio.[20]

The first months of Beovich's episcopacy were characterised by a cautious approach.[21] Having acknowledged his limited knowledge of parochial matters, Beovich retained the same inner circle of advisers that had served Killen.[21] He kept numerous engagements, including the opening of a maternity wing at Calvary Hospital with Premier Thomas Playford,[23] a meeting of the Holy Name Society that drew two thousand members,[24] and an Anzac Day requiem Mass for soldiers who had returned from the Second World War.[25] Privately, he began negotiations with the Australian apostolic delegate and bishop of Port Augusta Thomas McCabe regarding the founding of a seminary for Adelaide.[26]

In July 1940, Beovich arranged for a Catholic lawyer to draft a bill entitling religious ministers to give thirty minutes of religious instruction per week to students in government schools belonging to their denomination. Drafted as a compromise between the lack of religious education in state schools at the time, and mandatory instruction by schoolteachers (which had been opposed by the Adelaide Catholic diocese), it was introduced to state parliament as a private member's bill by then opposition leader Robert Richards. With the support of education minister Shirley Jeffries, the bill won passage through both houses of parliament and became law.[27]

Reconstruction and The Movement[edit]

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (March 2015) |

Retirement and later life[edit]

On 1 May 1971, Bishop Matthew Beovich sent his resignation to Pope Paul VI. Paying tribute to the quiet, calm way he usually faced difficulties, his secretary recalled that the only time he saw him excited was during World War II, at a meeting in the town hall to protest against the bombing of Rome. Although gentle and shy, he could appear remote and austere, but was affectionately remembered for his sense of humour and his `jet-propelled’ arrivals and departures from Catholic functions. Beovich died on 24 October 1981 in North Adelaide and was buried in West Terrace cemetery.

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (March 2015) |

Notes[edit]

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (March 2015) |

References[edit]

- ^ "Archdiocese of Adelaide - History". Archdiocese of Adelaide. Archived from the original on 28 December 2010. Retrieved 30 May 2010.

- ^ a b Laffin, Josephine (2007). "Matthew Beovich (1896–1981)". Australian Dictionary of Biography. Vol. 17. National Centre of Biography, Australian National University. ISSN 1833-7538. Retrieved 8 June 2010.

- ^ Laffin 2008, p. 14.

- ^ Laffin 2008, p. 20.

- ^ Laffin 2008, p. 21.

- ^ Laffin 2008, p. 35.

- ^ Laffin 2008, p. 42.

- ^ Laffin 2008, p. 43.

- ^ Laffin 2008, p. 65.

- ^ Laffin 2008, p. 66.

- ^ Laffin 2008, p. 71.

- ^ a b Laffin 2008, p. 72.

- ^ a b c Laffin 2008, p. 76.

- ^ Laffin 2008, p. 81.

- ^ Laffin 2008, p.89

- ^ Laffin 2008, p. 80

- ^ Laffin 2008, p. 92

- ^ Laffin 2008, p. 96

- ^ a b Laffin 2008, p. 106.

- ^ a b c Laffin 2008, p. 107.

- ^ a b c Laffin 2008, p. 112.

- ^ The first three bishops of Adelaide were not archbishops, since Adelaide only became an archdiocese in 1887. Beovich was the first Australian-born bishop of Adelaide, including those before and after Adelaide became an archdiocese.

- ^ Laffin 2008, p. 110.

- ^ Laffin 2008, p. 113.

- ^ Laffin 2008, p. 114.

- ^ Laffin 2008, p. 115.

- ^ Laffin 2008, p. 116.

- Laffin, Josephine (2008). Matthew Beovich - A Biography. Wakefield Press. ISBN 978-1-86254-817-6.

- Laffin, Josephine. "Beovich, Matthew (1896–1981)". Beovich, Matthew. Melbourne University Press. Retrieved 8 June 2010.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - Press, Margaret M. (1991). Colour and Shadow - South Australian Catholics 1906 - 1962. The Archdiocese of Adelaide. ISBN 0-646-04777-9.

- Ormonde, Paul (1972). The Movement. Thomas Nelson Limited. ISBN 017-001968-3.

External links[edit]

- Beovich, Matthew at the Australian Dictionary of Biography, Online Edition.