Drug abuse retinopathy

This article is an orphan, as no other articles link to it. Please introduce links to this page from related articles; try the Find link tool for suggestions. (March 2024) |

Drug abuse retinopathy is damage to the retina of the eyes caused by chronic drug abuse. Types of retinopathy caused by drug abuse include maculopathy, Saturday night retinopathy, and talc retinopathy. Common symptoms include temporary and permanent vision loss, blurred vision, and night blindness. Substances commonly associated with this condition include poppers, heroin, cocaine, methamphetamine, tobacco, and alcohol.[1]

Retinopathy[edit]

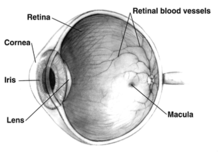

Retina is the innermost layer of the eye.[2] It is made up of three layers, namely the outer pigmented layer, the middle photoreceptor layer and the inner neural layer. The pigmented layer is responsible for absorbing light that penetrates inner neural layer. The photoreceptor layer consists of 2 kinds of photoreceptor cells, rod cells and cone cells. Rod cells have high sensitivity to light so they are responsible for night vision, but they cannot differentiate between colors, meaning that they only have black and white vision. Cone cells have low sensitivity to light, but they have the ability to differentiate between colors. These photoreceptors cells are unevenly distributed throughout the retina. The density of rod cells increases peripherally and the cone cells are concentrated at a region called macula where there are no rod cells.[2] This region is responsible for high-resolution and color vision.[2]

Maculopathy[edit]

Maculopathy is an eye disease that refers to breakdown of the macula.[3] Macula is the region on the retina containing the highest concentration of cone cells which is responsible for color vision.[2] Symptoms of maculopathy include a reduction in central vision acuity, distorted vision, and perceived flashes of light that occur without an actual light source.[4]

Saturday night retinopathy[edit]

Saturday night retinopathy is a condition that is due to central retinal or ophthalmic artery occlusion.[5] Common clinical features include ophthalmoplegia and orbital congestion.[6] The etiology of this condition is related to unconsciousness after drug use, leading to patient sleeping in an unusual position that continuously exerts pressure on the orbit.[5] This orbital compression will result in ophthalmic and central retinal artery occlusion which lead to ischemia in the inner retina and the patient may experience sudden unilateral blindness and eye pain.[6][7]

Talc retinopathy[edit]

Talc is a filler commonly added in tablet formulation acting as a glidant to improve the flowability of the drug powder.[citation needed] It is also frequently added as an adulterant in illicit drugs such as heroin and methamphetamine to increase its volume and weight and thus its street value.[8] When it is inhaled, it will enter the systemic circulation through the capillaries in the nasal mucosa.[9] After entering the systemic circulation, it will deposit in the retinal blood vessels and undergo reaction which lead to focal narrowing of retinal vessels.[10] This significantly reduces the blood flow to retina and eventually lead to retinal ischemia.[10] Clinical features include refractile yellow deposit seen under fundoscopy.[4] Patients may experience a reduction in visual field and visual acuity.[10]

Disease causing agents[edit]

Alkyl nitrites (poppers)[edit]

Poppers is an inhaled drug which contains a range of alkyl nitrites, such as isobutyl nitrite and amyl nitrite.[11] Despite its primary usage as a potent vasodilator,[11] its popularity among the homosexual community largely stems from its ability to facilitate anal sexual intercourse by relaxing the smooth muscles in the internal anal sphincter.[12] The use of intranasal poppers is associated with the development of macular degeneration through a poorly known mechanism. This condition may be the consequence of the increase in nitric oxide (NO) level following the oxidation of alkyl nitrites. The increase in NO level exerts a more significant stimulatory effect on guanylate cyclase, an enzyme found in cone cells.[13] Upon activation, guanylate cyclase converts more guanosine triphosphate (GTP) to cyclic guanosine monophosphate (cGMP). cGMP is involved in the photo-transduction pathway which allows calcium and sodium to enter and depolarize the cell.[14] A high level of cGMP results in high levels of calcium in the cells. The increase in intracellular cGMP and calcium level results in the production of reactive oxygen species (ROS) which damage macular cone cells and leading to macular degeneration.[14]

Heroin[edit]

Heroin is an opioid with a rapid onset of action after intravenously administration. Once being injected, it binds to the Mu receptors in the central nervous system within 15–20 seconds.[15] Users feel a sense of euphoria shortly after application, making it a highly addictive drug.[16] The use of intravenous heroin is associated with the development of Saturday Night retinopathy.[1] Currently, no specific treatment is deemed effective in treating Saturday Night retinopathy as the ischemic injury caused by prolonged compression by external forces is irreversibly dealt to the retinal vasculature.[5] In the case of a high intraocular pressure, an anterior chamber paracentesis or a lateral canthotomy can be considered if standard treatments have failed.[5] Other symptoms, such as proptosis, enlargement of the extraocular muscles, and eye pain seem to resolve in the absence of intervention.[5] As with other drug-related problems, patients should be evaluated for other heroin-related sequelae and be referred accordingly.[5]

Cocaine[edit]

Cocaine is a central nervous system stimulant which can be used recreationally to produce a euphoric effect.[17] Cocaine is associated with retinal toxicity mainly through its negative impacts on the retinal vasculature.[18] Cocaine use causes increased norepinephrine levels and the resulting sympathetic activation leads to vasospasm and hypertension,[19] both of which are risk factors to retinal blood vessel damage.

Related retinal vasculature conditions include central retinal artery occlusion,[20] central retinal vein occlusion[21] and cilioretinal artery occlusion.[22] The occlusion of retinal blood vessels reduces blood supply to the retina, which causes tissue ischemia. Insufficient blood flow deprives the retina of oxygen, removal of waste metabolites and nutrients.[23] This prevents proper retinal homeostasis and causes tissue injury. Over a long period of time, tissue damage accumulates and leads to tissue death or retinal infarction.[23] The duration of cocaine use is a major contributing factor to the severity of adverse retinal effect.[24]

Cocaine use is also associated with retinal hemorrhage due to the general increase in blood pressure and blood vessel occlusion within the retina.[25] Signs and symptoms of retinal hemorrhage include painless unilateral floaters, seeing a red hue, cobwebs, haze, shadows, and visual loss.[26] More advanced retinal hemorrhage may limit visual acuity and fields and may lead to the formation of a blind spot.[26] Vision is often poorer in the morning. Treatments of retinal hemorrhage include cryotherapy and laser therapy.[26]

Methamphetamine[edit]

Methamphetamine is a highly addictive stimulant that stimulates the release of dopamine in the brain. The common manufacturing process of methamphetamine includes the reduction of over-the-counter nasal decongestant such as pseudoephedrine which contains talc as filler.[9] Therefore, intranasal or intravenous use of methamphetamine is associated with talc retinopathy.[1] There is no treatment for talc retinopathy but cessation of methamphetamine plays a role in preventing further reduction in visual field and acuity.

Tobacco[edit]

Nicotine is a highly addictive substance found in tobacco products such as cigarettes, cigars, and chewing tobacco.[27] When nicotine is inhaled or consumed, it enters the bloodstream and damages the blood vessels the eyes.[28] Common symptoms include blurred vision, dark spots in the vision, and even blindness in severe cases.[28] The exact mechanisms by which nicotine causes retinopathy are not fully understood. However, it is believed that nicotine can cause oxidative stress and inflammation, leading to ocular vascular damage.[29] Additionally, nicotine can cause constriction of the blood vessels, reducing blood flow to the eyes and making them more vulnerable to damage and disease.[30] It is recommended that smokers exhibiting signs and symptoms of retinopathy engage in smoking cessation to improve their quality of life.[31][32]

Alcohol[edit]

Heavy alcohol use is associated with higher blood pressure levels.[33] The consumption of alcohol leads to the release of renin, an enzyme that aids in the activation of a hormone called angiotensin II.[34] This hormone causes blood vessels to constrict and increases blood pressure. This relationship is particularly pronounced in people with diabetes.[35] Elevated blood pressure can damage the delicate blood vessels in the eye and lead to retinopathy.[35]

The hepatic metabolism of excess alcohol leads to an increase in the level of endogenous toxins,[36] such as methanol, which is often present in homemade alcohol[37] This causes swelling of the eye and optic nerve and damage to the retina, especially in people who have underlying liver disease or who are already at risk for retinopathy due to diabetes.[38] Alcohol-induced liver disease can also exacerbate other health conditions that contribute to retinopathy, such as hypertension[39] and hyperglycemia.[39][40]

Alcohol consumption leads to abnormalities in the metabolism pathways of several essential nutrients for eye health such as vitamin A and zinc. Alcohol undergoes oxidative metabolism in the liver and is converted to acetaldehyde, then to acetic acid.[41] Retinol, the form of vitamin A in food and dietary supplements, is oxidatively metabolized following a similar pathway, being converted to retinal and retinoic acid, the active form of vitamin A.[41] Excessive alcohol consumption places a heavy burden on the enzymes catalyzing these reactions and leads to poor vitamin A homeostasis.[41] Besides, alcohol mediates the modulation of zinc transporters and leads to a decrease in levels of zinc in the body.[42] This results in retinopathic symptoms such as nyctalopia[41] and macular degeneration.[42]

References[edit]

- ^ a b c Dhingra D, Kaur S, Ram J (September 2019). "Illicit drugs: Effects on eye". The Indian Journal of Medical Research. 150 (3): 228–238. doi:10.4103/ijmr.IJMR_1210_17. PMC 6886135. PMID 31719293.

- ^ a b c d Martini F, Nath J, Bartholomew E (2014). Fundamentals of Anatomy and Physiology Global Edition (10th ed.). Pearson Education, Limited. p. 601. ISBN 9781292057217.

- ^ "Age-Related Macular Degeneration (AMD) | National Eye Institute". www.nei.nih.gov. Archived from the original on 2023-03-06. Retrieved 2023-03-09.

- ^ a b Peragallo J, Biousse V, Newman NJ (November 2013). "Ocular manifestations of drug and alcohol abuse". Current Opinion in Ophthalmology. 24 (6): 566–573. doi:10.1097/icu.0b013e3283654db2. PMC 4545665. PMID 24100364.

- ^ a b c d e f Malihi M, Turbin RE, Frohman LP (April 2015). "Saturday Night Retinopathy with Ophthalmoplegia: A Case Series". Neuro-Ophthalmology. 39 (2): 77–82. doi:10.3109/01658107.2014.997889. PMC 5123184. PMID 27928336.

- ^ a b Nguyen HV, North VS, Oellers P, Husain D (2018-06-01). "Saturday Night Retinopathy After Intranasal Heroin". Journal of VitreoRetinal Diseases. 2 (4): 227–231. doi:10.1177/2474126418779512. ISSN 2474-1264. S2CID 81487255.

- ^ Hayreh SS (2014-12-08). "Retinal Survival Time and Visual Outcome in Central Retinal Artery Occlusion". Ocular Vascular Occlusive Disorders. Cham: Springer International Publishing. pp. 193–219. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-12781-1_11. ISBN 978-3-319-12780-4.

- ^ Shah VA, Cassell M, Poulose A, Sabates NR (April 2008). "Talc retinopathy". Ophthalmology. 115 (4): 755–755.e2. doi:10.1016/j.ophtha.2007.10.043. PMID 18387416.

- ^ a b Kumar RL, Kaiser PK, Lee MS (September 2006). "Crystalline retinopathy from nasal ingestion of methamphetamine". Retina. 26 (7): 823–824. doi:10.1097/01.iae.0000244275.03588.ad. PMID 16963858.

- ^ a b c Kaga N, Tso MO, Jampol LM (October 1982). "Talc retinopathy in primates: a model of ischemic retinopathy. III. An electron microscopic study". Archives of Ophthalmology. 100 (10): 1649–1657. doi:10.1001/archopht.1982.01030040627015. PMID 7138334.

- ^ a b Schmidt AJ, Bourne A, Weatherburn P, Reid D, Marcus U, Hickson F (December 2016). "Illicit drug use among gay and bisexual men in 44 cities: Findings from the European MSM Internet Survey (EMIS)". The International Journal on Drug Policy. 38: 4–12. doi:10.1016/j.drugpo.2016.09.007. PMID 27788450.

- ^ Le A, Yockey A, Palamar JJ (2020). "Use of "Poppers" among Adults in the United States, 2015-2017". Journal of Psychoactive Drugs. 52 (5): 433–439. doi:10.1080/02791072.2020.1791373. PMC 7704544. PMID 32669067.

- ^ Bral NO, Marinkovic M, Leroy BP, Hoornaert K, van Lint M, ten Tusscher MP (February 2016). "Do not turn a blind eye to alkyl nitrite (poppers)!". Acta Ophthalmologica. 94 (1): e82–e83. doi:10.1111/aos.12753. PMID 25975842. S2CID 39061955.

- ^ a b Sharma AK, Rohrer B (March 2007). "Sustained elevation of intracellular cGMP causes oxidative stress triggering calpain-mediated apoptosis in photoreceptor degeneration". Current Eye Research. 32 (3): 259–269. doi:10.1080/02713680601161238. PMID 17453946. S2CID 13071358.

- ^ Huecker MR, Koutsothanasis GA, Abbasy MS, Marraffa J (2022). "Heroin". StatPearls. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing. PMID 28722906. Archived from the original on 2023-01-19. Retrieved 2023-03-10.

- ^ Hosztafi S (2011). "[Heroin addiction]". Acta Pharmaceutica Hungarica. 81 (4): 173–183. PMID 22329304. Archived from the original on 2023-03-10. Retrieved 2023-03-10.

- ^ Ramamoorthy J, Murphy NE (2017). McEvoy MD, Furse CM (eds.). "Cocaine Intoxication and Hypertensive Emergency". Oxford Medicine Online. doi:10.1093/med/9780190226459.003.0089.

- ^ Karbach N, Kobrenko N, Myers M, Gurwood AS. "How Drug Abuse Affects the Eye". Review of Optometry. Archived from the original on 2023-03-10. Retrieved 2023-03-10.

- ^ Isner JM, Chokshi SK (December 1989). "Cocaine and vasospasm". The New England Journal of Medicine. 321 (23): 1604–1606. doi:10.1056/NEJM198912073212309. PMID 2586556.

- ^ Devenyi P, Schneiderman JF, Devenyi RG, Lawby L (January 1988). "Cocaine-induced central retinal artery occlusion". CMAJ. 138 (2): 129–130. PMC 1267540. PMID 3334923.

- ^ Sleiman I, Mangili R, Semeraro F, Mazzilli S, Spandrio S, Balestrieri GP (August 1994). "Cocaine-associated retinal vascular occlusion: report of two cases". The American Journal of Medicine. 97 (2): 198–199. doi:10.1016/0002-9343(94)90033-7. PMID 8059789.

- ^ Kannan B, Balaji V, Kummararaj S, Govindarajan K (2011). "Cilioretinal artery occlusion following intranasal cocaine insufflations". Indian Journal of Ophthalmology. 59 (5): 388–389. doi:10.4103/0301-4738.83619. PMC 3159324. PMID 21836348.

- ^ a b Osborne NN, Casson RJ, Wood JP, Chidlow G, Graham M, Melena J (January 2004). "Retinal ischemia: mechanisms of damage and potential therapeutic strategies". Progress in Retinal and Eye Research. 23 (1): 91–147. doi:10.1016/j.preteyeres.2003.12.001. PMID 14766318. S2CID 8337398.

- ^ Tran KH, Ilsen PF (August 2007). "Peripheral retinal neovascularization in talc retinopathy". Optometry. 78 (8): 409–414. doi:10.1016/j.optm.2007.02.018. PMID 17662930.

- ^ Newman NM, DiLoreto DA, Ho JT, Klein JC, Birnbaum NS (January 1988). "Bilateral optic neuropathy and osteolytic sinusitis. Complications of cocaine abuse". JAMA. 259 (1): 72–74. doi:10.1016/0002-9394(88)90347-9. PMID 3334775.

- ^ a b c "Vitreous Hemorrhage: Diagnosis and Treatment". American Academy of Ophthalmology. March 2007. Retrieved 2023-03-13.

- ^ West R (August 2017). "Tobacco smoking: Health impact, prevalence, correlates and interventions". Psychology & Health. 32 (8): 1018–1036. doi:10.1080/08870446.2017.1325890. PMC 5490618. PMID 28553727.

- ^ a b Ciesielski M, Rakowicz P, Stopa M (July 2019). "Immediate effects of smoking on optic nerve and macular perfusion measured by optical coherence tomography angiography". Scientific Reports. 9 (1): 10161. Bibcode:2019NatSR...910161C. doi:10.1038/s41598-019-46746-z. PMC 6629612. PMID 31308472.

- ^ Khademi F, Totonchi H, Mohammadi N, Zare R, Zal F (2019). "Nicotine-Induced Oxidative Stress in Human Primary Endometrial Cells". International Journal of Toxicology. 38 (3): 202–208. doi:10.1177/1091581819848081. PMID 31113282. S2CID 162171085.

- ^ Benowitz NL, Burbank AD (August 2016). "Cardiovascular toxicity of nicotine: Implications for electronic cigarette use". Trends in Cardiovascular Medicine. 26 (6): 515–523. doi:10.1016/j.tcm.2016.03.001. PMC 4958544. PMID 27079891.

- ^ Sung SY, Chang YC, Wu HJ, Lai HC (June 2022). "Polycythemia-Related Proliferative Ischemic Retinopathy Managed with Smoking Cessation: A Case Report". International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 19 (13): 8072. doi:10.3390/ijerph19138072. PMC 9265410. PMID 35805729.

- ^ Cai X, Chen Y, Yang W, Gao X, Han X, Ji L (November 2018). "The association of smoking and risk of diabetic retinopathy in patients with type 1 and type 2 diabetes: a meta-analysis". Endocrine. 62 (2): 299–306. doi:10.1007/s12020-018-1697-y. PMID 30128962. S2CID 52047306.

- ^ Tasnim S, Tang C, Musini VM, Wright JM (July 2020). "Effect of alcohol on blood pressure". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2020 (7): CD012787. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD012787.pub2. PMC 8130994. PMID 32609894.

- ^ Puddey IB, Vandongen R, Beilin LJ, Rouse IL (July 1985). "Alcohol stimulation of renin release in man: its relation to the hemodynamic, electrolyte, and sympatho-adrenal responses to drinking". The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism. 61 (1): 37–42. doi:10.1210/jcem-61-1-37. PMID 3889040.

- ^ a b Gillow JT, Gibson JM, Dodson PM (September 1999). "Hypertension and diabetic retinopathy--what's the story?". The British Journal of Ophthalmology. 83 (9): 1083–1087. doi:10.1136/bjo.83.9.1083. PMC 1723193. PMID 10460781.

- ^ Cederbaum AI (November 2012). "Alcohol metabolism". Clinics in Liver Disease. 16 (4): 667–685. doi:10.1016/j.cld.2012.08.002. PMC 3484320. PMID 23101976.

- ^ Sharma P, Sharma R (2011). "Toxic optic neuropathy". Indian Journal of Ophthalmology. 59 (2): 137–141. doi:10.4103/0301-4738.77035. PMC 3116542. PMID 21350283.

- ^ Lee CC, Stolk RP, Adler AI, Patel A, Chalmers J, Neal B, et al. (October 2010). "Association between alcohol consumption and diabetic retinopathy and visual acuity-the AdRem Study" (PDF). Diabetic Medicine. 27 (10): 1130–1137. doi:10.1111/j.1464-5491.2010.03080.x. PMID 20854380. S2CID 205550640. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2019-02-18. Retrieved 2023-06-09.

- ^ a b Osna NA, Donohue TM, Kharbanda KK (2017). "Alcoholic Liver Disease: Pathogenesis and Current Management". Alcohol Research. 38 (2): 147–161. PMC 5513682. PMID 28988570.

- ^ Hsieh PH, Huang JY, Nfor ON, Lung CC, Ho CC, Liaw YP (October 2017). "Association of type 2 diabetes with liver cirrhosis: a nationwide cohort study". Oncotarget. 8 (46): 81321–81328. doi:10.18632/oncotarget.18466. PMC 5655286. PMID 29113391.

- ^ a b c d Clugston RD, Blaner WS (May 2012). "The adverse effects of alcohol on vitamin A metabolism". Nutrients. 4 (5): 356–371. doi:10.3390/nu4050356. PMC 3367262. PMID 22690322.

- ^ a b Grahn BH, Paterson PG, Gottschall-Pass KT, Zhang Z (April 2001). "Zinc and the eye". Journal of the American College of Nutrition. 20 (2 Suppl): 106–118. doi:10.1080/07315724.2001.10719022. PMID 11349933. S2CID 12282463.