Old Town Hall, Clitheroe

| Old Town Hall, Clitheroe | |

|---|---|

Old Town Hall, Clitheroe | |

| Location | Church Street, Clitheroe |

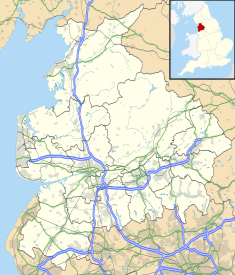

| Coordinates | 53°52′24″N 2°23′26″W / 53.8732°N 2.3905°W |

| Built | 1820 |

| Architect | Thomas Rickman |

| Architectural style(s) | Gothic Revival style |

Listed Building – Grade II | |

| Official name | Town Hall |

| Designated | 30 September 1976 |

| Reference no. | 1072374 |

The Old Town Hall, sometimes referred to as the Moot Hall, is a municipal building in Church Street, Clitheroe, Lancashire, England. The structure, which was the meeting place of Clitheroe Borough Council, is a Grade II listed building.[1]

History[edit]

The first municipal building in Clitheroe was a moot hall built on Church Street in about 1610.[2] It contained prison cells with barrel vaulted ceilings which were cut out of solid rock and were used to accommodate petty criminals on their way to imprisonment in Lancaster Castle.[3] In the early 19th century borough officials decided to demolish those parts of the old moot hall which were above ground and to erect a new structure on the same site.[4]

The new building was designed by Thomas Rickman in the Gothic Revival style, built in ashlar stone and was completed in 1820.[5] The design involved an asymmetrical main frontage with four bays facing onto the Church street; on the ground floor, there was an arched doorway flanked by colonettes in the left hand bay and lancet windows in the other bays.[1] Between the storeys there were five armorial shields, on the first floor there was a central three-light window with lancet windows in the outer bays and, at roof level, there was an octagonal spire with a weathervane, which was 62 feet (19 m) high.[6] Internally, the principal room was the council chamber which featured leaded windows and was accessed by a spiral staircase.[2] The prison cells were retained, in situ, from the older building.[2]

The quarterly assizes and the magistrates' court hearings were held in the building from about 1825[6] and the town became a municipal borough with the building as its headquarters in 1835.[7] It was at the town hall that David Shackleton was elected unopposed as the Labour Member of Parliament in the 1902 Clitheroe by-election; he was only the third Labour MP ever to be elected to the UK Parliament.[8]

The town hall continued to serve as the headquarters of the borough council for much of the 20th century[9] but ceased to be the local seat of government when the enlarged Ribble Valley District Council was established in 1974.[10] The district council was initially based at offices in Clitheroe Castle[11] before moving to purpose-built offices in Church Walk in the late 1970s.[12] Clitheroe Town Council, which was established in 1974, chose to establish its offices on the opposite side of the road in the former borough treasurer's office, No. 9 Church Street, rather than using the old town hall.[4] However, the town council continued to use the old town hall for its annual mayor-making ceremonies.[13] An extensive programme of refurbishment works was carried out in the late 1980s, enabling the town hall to be integrated into the Clitheroe Library: the council chamber was subsequently used as an events venue for lectures and concerts[4] and the prison cells were used for storage purposes.[2]

Works of art in the former council chamber include a portrait by the Australian painter, James Peter Quinn, of the local historian and author, William Self Weeks.[14][15]

See also[edit]

References[edit]

- ^ a b Historic England. "Town Hall (1072374)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 4 August 2021.

- ^ a b c d "Clitheroe Town Trail" (PDF). Clitheroe Civic Society. p. 3. Retrieved 4 August 2021.

- ^ "Clitheroe". Heritage Open Days. Archived from the original on 18 September 2015. Retrieved 4 August 2021.

- ^ a b c "Town Council History". Clitheroe Town Council. Retrieved 4 August 2021.

- ^ Hartwell, Clare; Pevsner, Nikolaus (2009) [1969], Lancashire: North, The Buildings of England, New Haven and London: Yale University Press, p. 242, ISBN 978-0-300-12667-9

- ^ a b Farrer, William; Brownbill, J. (1911). "'Townships: Clitheroe', in A History of the County of Lancaster". London: British History Online. pp. 360–372. Retrieved 4 August 2021.

- ^ "Clitheroe MB". Vision of Britain. Retrieved 4 August 2021.

- ^ Martin, Ross Murdoch (2000). The Lancashire Giant David Shackleton, Labour Leader and Civil Servant. Liverpool University Press. p. 42. ISBN 978-0853239345.

- ^ "No. 44469". The London Gazette. 5 December 1967. p. 13296.

- ^ Local Government Act 1972. 1972 c.70. The Stationery Office Ltd. 1997. ISBN 0-10-547072-4.

- ^ "No. 46391". The London Gazette. 1 November 1974. p. 10531.

- ^ "No. 48668". The London Gazette. 2 July 1981. p. 8859.

- ^ "Clitheroe prepares for Mayor-making parade". Clitheroe Advertiser. 1 May 2014. Retrieved 4 August 2021.

- ^ Quinn, James Peter. "Wiiliam Self Weeks". Art UK. Retrieved 4 August 2021.

- ^ Weeks, William Self (1927). Clitheroe in the Seventeenth Century. Advertiser and Times Co.