Dorothy Thursby-Pelham

Dorothy Thursby-Pelham | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | 24 October 1884 Gosforth, Cumberland, England |

| Died | 1972 Leominster, Herefordshire, England |

| Resting place | Goodrich, Herefordshire |

| Alma mater | University of Cambridge |

| Known for | Illustrations of emperor penguin embryos from the Terra Nova expeditions, studies of North Sea plaice |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields |

|

| Institutions | |

Dorothy Elizabeth Thursby-Pelham (1884–1972) was a scientist at the Zoological Laboratory, University of Cambridge and subsequently at the Ministry of Agriculture, Fisheries and Food (United Kingdom) - Directorate of Fisheries laboratory in Lowestoft (now known as the Centre for Environment, Fisheries and Aquaculture Science) who has been called 'England's first female sea-going fisheries scientist' and was an active member of the International Council for the Exploration of the Sea (ICES).[1]

She is best known as the illustrator of several well-known images of emperor penguin embryos based on eggs collected during the Terra Nova expedition between 1910 and 1913, but was also an active fisheries scientist who collected extensive datasets on plaice (Pleuronectes platessa) in the North Sea, and who gave several memorable interviews to the BBC on national radio in the 1930s and 1950s.

University of Cambridge and the Terra Nova Expedition[edit]

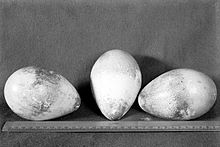

Thursby-Pelham worked as an assistant to Dr Richard Assheton (1863-1915), Lecturer in Animal Embryology at the University of Cambridge. It was during this time that she produced a series of intricate and beautiful pencil drawings of the embryos of the Emperor Penguin eggs famously collected on Scott's last expedition (1910-1913) to the Antarctic.[2] This expedition, commemorated in Apsley Cherry-Garrard's 1922 book The Worst Journey in the World[3] (which contained Ewart's report on the Emperor Penguin as an Appendix), aimed to be the first to reach the South Pole, collecting as much scientific data as possible along the way. In particular, it was hoped that evidence would be found about the embryos of Emperor Penguins (thought to be the most 'primitive' of the bird species) to support the theory that there was an evolutionary link between birds and reptiles. In 1911, Edward Adrian Wilson, the expedition's chief scientist, and two colleagues embarked on a gruelling five-week journey to the nearest penguin breeding colony, pulling heavy sledges in total darkness through temperatures of -40 °C. They collected five fresh eggs, three of which survived the return journey. Back in Britain, the pickled embryos were sliced and mounted onto slides, with Richard Assheton being assigned the special task of analysing them. It was at this time that Dorothy Thursby-Pelham made her pencil drawings.[2]

Fisheries research[edit]

Thursby-Pelham, England's first female seagoing scientist.,[1] was also the first woman to play a visible role in the International Council for the Exploration of the Sea, contributing papers, attending meetings and serving as assistant editor of the ICES Journal of Marine Science.[4] In a photograph taken outside the House of Lords in April 1929, Dorothy Thursby-Pelham is one of only 3 women scientists among 64 men on the ICES Council.[4]

Thursby-Pelham made extensive surveys of the plaice population in the southern North Sea during the 1930s's.[1] She used annual rings on the otoliths to construct age distributions in stock density by quarter years for a period of about ten years. She was also engaged in tagging and transplantation of plaice from one North Sea sandbank to another. The importance of Thursby-Pelham's work lies in the subsequent use by Ray Beverton and Sidney Holt. Datasets collected by Dorothy Thursby-Pelham were acknowledged by the authors as being instrumental for the writing of the ground-breaking book On the Dynamics of Exploited Fish Populations[5] in 1957.

In 1936 Thursby-Pelham published an account of The Decline in the Lowestoft Plaice Fisheries as a result of overfishing.[6] This situation continued up until the beginning of World War II, when a cessation of fishing pressure helped to alleviate the situation[7]

Thursby-Pelham established government fisheries data-collection programmes that continue in England today. Daily returns of the quantity (Hundredweight) of fish landed at each port, and the average value (£) per Hundredweight. were instigated, together with recording the number of hours fishing by each vessel. In recent years, these historical datasets, together with more recent information have been digitized and used to demonstrate major changes in plaice and sole distribution over the 20th Century, associated with long-term climate change in the North Sea and patterns of fishing pressure.[7]

Appearances on the BBC[edit]

Thursby-Pelham gave several memorable interviews to the BBC in the 1930s and 1950s. Each of these appearances was documented in the Radio Times.

Radio Times: Issue 677, 22 September 1936 - Pages 35 and 36.[8] Fish Alive and Dead. This week and next, Miss Thursby-Pelham, who does research work at the Fisheries Laboratory, Lowestoft, is to talk about fish both in the sea, and on the fishmonger's slab. She goes to sea for a week at a time in a trawler belonging to the Ministry of Agriculture and Fisheries, and its whole purpose is to find out, by taking samples of fish, their food, and the water in which they swim, how fish live. Today she is to tell listeners the life story of two of the commonest fish - the cod and the plaice. Cod in the more northern seas ; millions of eggs, many of them devoured, many never fertilized, the tiny fry hatched out in winter in a world of enemies, seeking in jellyfish nurses to protect them. Plaice hatched out on sandy shallow shores, relying on their colour to protect them, growing very slowly, taking several years to reach edible size. Miss Thursby-Pelham's talk will pass on to fish for the table. Fish to buy; cooking hints; recipes. And she gives the valuable advice not to be afraid to buy fish when it is cheap. It is cheap when there is a glut of it, and gluts of fish are only obtainable when they are in prime condition.[8]

Radio Times: Issue 678, 25 September 1936 - Page 33.[9] Fish Alive and Dead. Most of us know that herrings are sold as fresh herrings, bloaters, kippers, and so on. But probably few knew that when small the plebeian herring is an aristocrat, for little herrings, with little sprats and little mackerel, make up the whitebait of Mayfair. Today Miss Thursby-Pelham is to tell their life-story. The reason why herrings are in season throughout the year is that they spawn at different times. Various families collect and go on honeymoon trips. When they are in these shoals the fishermen catch them. If they were dear, they would be prized more; they are the freshest that you can buy... and Miss Thursby-Pelham will tell listeners why British housewives should buy them.[9]

Thursby-Pelham appeared on the BBC "Light Programme" in 1952. Specifically she is cited in the Radio Times as appearing on "Woman’s Hour" (14:00, Friday 17 October 1952) Fish Need not be Tasteless. Dorothy Thursby-Pelham , who used to go to sea with the fishing fleet, explains how to cook fish so as to keep its flavour.[10]

External links[edit]

References[edit]

- ^ a b c MAFF (1992). The Directorate of Fisheries Research: Its Origins and Development. Ministry of Agriculture, Fisheries and Food, Lowestoft. 332pp.

- ^ a b Letters in the limelight: penguin eggs from Antarctica. http://libraryblogs.is.ed.ac.uk/towardsdolly/tag/thursby-pelham/ Accessed 31 May 2018.

- ^ Cherry-Garrard, Apsley (1922). The Worst Journey in the World. London: Carroll & Graf. ISBN 978-0-88184-478-8. OCLC 20136739

- ^ a b Rozwadowski, H.M. (2002) The Sea Knows No Boundaries: A Century of Marine Science under ICES. University of Washington Press. 448pp.

- ^ Beverton, R. J. H., and Holt, S. J. 1957. On the Dynamics of Exploited Fish Populations. Fishery Investigations Series II. Ministry of Agriculture, Fisheries and Food, London. 533 pp.

- ^ Thursby-Pelham, D.E. (1936) The Decline in the Lowestoft Plaice Fisheries, ICES Journal of Marine Science, 11 (1), 33–42.

- ^ a b Engelhard, G. H., Pinnegar, J. K., Kell, L. T., and Rijnsdorp, A. D. 2011. Nine decades of North Sea sole and plaice distribution. ICES Journal of Marine Science, 68: 1090–1104.

- ^ a b Radio Times,Issue 677, 22 September 1936 - Pages 35 and 36. https://genome.ch.bbc.co.uk/a25161a54ad24ebb9b1f3d17a215750c Accessed 31 May 2018.

- ^ a b Radio Times,Issue 678, 25 September 1936 - Pages 33. https://genome.ch.bbc.co.uk/efe6e768cb4e439abc3be9cfc03705b6 Accessed 31 May 2018.

- ^ Radio Times,Issue 1509, 10 October 1952 - Pages 37. https://genome.ch.bbc.co.uk/985c51r9c98148938bb627a38b31b192[permanent dead link] Accessed 31 May 2018.