History of Peru (1821–1842)

Peruvian Republic República Peruana | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1821–1842 | |||||||||

| Motto: "Firme y feliz por la unión" (Spanish) "Firm and Happy for the Union" | |||||||||

| Anthem: "Himno Nacional del Perú" (Spanish) "National Anthem of Peru" | |||||||||

| |||||||||

| Capital | Lima | ||||||||

| Common languages | Spanish | ||||||||

| Religion | Roman Catholicism | ||||||||

| Demonym(s) | Peruvian | ||||||||

| Government | Several[a] | ||||||||

| President | |||||||||

• 1821–1822 (first) | José de San Martín | ||||||||

• 1841–1842 (last) | Manuel Menéndez | ||||||||

| Legislature | National Congress | ||||||||

| Historical era | War of Independence | ||||||||

| 28 July 1821 | |||||||||

| 1822–1823 | |||||||||

| 26–27 July 1822 | |||||||||

| 20 September 1822 | |||||||||

| 9 December 1824 | |||||||||

| 28 October 1836 | |||||||||

| 20 January 1839 | |||||||||

| 1839–1841 | |||||||||

| 16 August 1842 | |||||||||

| Currency | Real | ||||||||

| |||||||||

| History of Peru |

|---|

|

|

|

The history of Peru between 1821 and 1842 is the period considered by the country's official historiography as the first stage of the its republican history, formally receiving the name of Foundational Period of the Republic (Spanish: Época Fundacional de la República) by historian Jorge Basadre. During this era, what became known as the First Militarism (Spanish: Primer Militarismo), a period where several military figures held control of the country, started in 1827 with José de La Mar's presidency, ending in 1844.

The twenty-year period begins on July 28, 1821, when General José de San Martín of the Liberating Expedition of Peru declared the Independence of Peru to a crowd gathered under the balcony of the Casa del Oidor, located at the main square of Lima, until then the capital of the Viceroyalty of Peru. However, Basadre claims that the period only begins, sensu stricto, with the installation of the first Constituent Congress on September 20, 1822.[1]

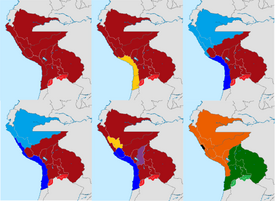

During this period, the newly formed Peruvian State not only established itself as a proper country, but notably attempted to both expand its territory and preserve its territorial integrity due to the overlapping disputes that arose from the end of the Spanish American wars of independence. To the north, Colombia (which already claimed territory located south of the Caquetá River) declared war on Peru after the latter's military occupation of Bolivia, then under Bolivarian influence. The war concluded without a clear victor through the signing of the Treaty of Guayaquil. After the dissolution of the Greater Colombian state, Ecuador regained its independence and pursued a dispute of its own.

Meanwhile, to the south, another war saw the division of Peru through the establishment of North Peru and South Peru, which shortly after joined Bolivia as the Peru–Bolivian Confederation that was ultimately dissolved in 1839 after a three-year war. With a reunited Peruvian state now reestablished, now president Agustín Gamarra unsuccessfully sought to annex its southern neighbour, which cost him his life during the Battle of Ingavi on November 18, 1841. Gamarra was succeeded by interim President Manuel Menéndez, but his death led to political instability and ultimately served as the beginning of a period of anarchy where multiple generals declared themselves the head of state, beginning with Juan Crisóstomo Torrico on August 16, 1842.

Background[edit]

After the Independence of Chile, General José de San Martín, on August 20, 1820, at the head of the Liberating Expedition of Peru, set sail from Valparaíso and landed in the Bay of Paracas in September of that year. He then settled in Pisco from where he sent delegates to convince viceroy Joaquín de la Pezuela to collaborate with independence, which he refused.

Given this response, San Martín moved to Huaura, near Lima, and sent his lieutenant Juan Antonio Álvarez de Arenales to the mountains where he defeated the royalists in the Battle of Cerro de Pasco. Later, Viceroy Pezuela was removed from the government and José de la Serna was appointed as the new Viceroy of Peru. He decided to meet with San Martín in Punchauca, but they did not reach any agreement, due to the problems that arose due to the advance of San Martín and his troops.

Viceroy La Serna and his troops ultimately left for the mountains. Consequently, San Martín arrived in Lima and proclaimed the independence of Peru on July 28, 1821, while standing on the balcony of the Casa del Oidor, located at the main square:[2]

From this moment Peru is free and independent by the general will of the people and by the justice of its cause that God defends. Long live the Homeland! Long live freedom! Long live independence!

— José de San Martín (July 18, 1821)[3]

Government of San Martín (1821–1822)[edit]

San Martín had assumed the military and political command of the so-called free departments of Peru under the title of Protector, as stated in the decree of August 3, 1821. For all practical purposes, Peru was divided militarily and administratively into two parts: that of Lima, the northern coast and the central highlands (under the control of the Patriots) and that of the central and southern parts, headquartered in Cuzco and controlled by the Royal Army of Peru.

Later, the title of Protector was changed to Protector of the Freedom of Peru. During the Protectorate, which lasted just one year and 17 days, the following administrative policies were implemented:

- The beginning of an autonomous administrative regime after three centuries of Spanish rule.

- Possibility for the people to choose the system that best suits national interests.

- The symbols of the country: the first flag and the national anthem.

- The national currency, fiduciary sign of free economic power.

- Basic regulation of its commercial system to initiate economic relations with other countries in the world.

- The creation of the Peruvian Navy and the acquisition of the first ships for its national squadron in order to defend the acquired sovereignty.

- The basic organization of its military force, to protect internal and external security.

- The determination of its own educational performance with the founding of the Normal School, as well as the first public schools of free Peru.

- The first attempt to rescue, value and disseminate national culture through the creation of the National Library of Peru.

The Protectorate was a dictatorship that was based on a Statute, which had the following characteristics:

- The Statute of Government was a provisional and emergency norm, corresponding to a revolutionary situation for an emerging state, which had achieved its partial independence and was trying to complete it.

- In its declarative principles it was liberal in nature, because it included the defence of human rights, which had inspired the French Revolution and the American Revolutionary War.

- The territorial organization of the independent State was based on the departmental system.

- The Upper Chamber of Justice replaced the Royal Court of Lima and assumed the legal and political functions of the country.

- It was proposed to create a Council of State, which would support the Protector in his government, made up of several members, among whom would be 3 Creole counts and an Inca marquis.

Other provisions that occurred in Peru, during the Protectorate, were:

- In a conservative measure, San Martín respected all the titles of the viceregal nobility, changing the name of Titles of Castile to Titles of Peru.

- The Patriotic Society of Lima (Spanish: Sociedad Patriótica de Lima) was founded, with the intention of defending the establishment of a Peruvian monarchical regime, of which San Martín was a supporter; but, in practice, its members advocated the republican system.

- The Order of the Sun of Peru was created to recognize the work of the most distinguished Peruvians and give them a status similar to that of the Titles of Peru.

- A special commission, made up of Juan García del Río and James Paroissien, traveled to Europe by order of San Martín to look for a prince to come to Peru as king. They left Peru in December 1821 and arrived in London in September 1822, the time when the Protectorate was coming to an end. Although they were replaced by Ortiz de Zevallos and John Parish Robertson, the idea of the republican system had been consolidated in Peru, therefore, the commissioners failed in their attempts.

- The first members of San Martín's cabinet were: Juan García del Río, Minister of Foreign Affairs; Bernardo de Monteagudo, Minister of War and Navy; and Hipólito Unanue, Minister of Finance. The first was a native of Cartagena de Indias, the second from the province of Tucumán and the third from Arica.

- José de la Riva Agüero, a young and rich aristocrat from Lima who had collaborated intensely for the cause of freedom, was appointed Prefect of Lima.

Disaster at Macacona[edit]

San Martín's main issue was that of the war against the royalists, with some reproaching him for not undertaking a total offensive against them as he had done in Chile. However, he was aware of the numerical inferiority of his forces, compared to that of the viceregals who dominated the interior of the country from Jauja to Upper Peru, and numbered a total of 23,000 soldiers, mostly Andean and mestizo recruits. San Martín only had 4,000 troops. An important triumph for the patriots was the surrender of the fortresses of Callao on September 19, 1821, whose leader, Marshal José de La Mar, joined the patriot cause. Meanwhile, Viceroy La Serna reorganized his forces in the central and southern mountains of Peru and in Upper Peru, from where he carried out raids on the coast, destroying a patriot army in the battle of Ica (or La Macacona), on April 7. of 1822.

Independence of Quito[edit]

On May 24, 1822, Peruvian–Colombian troops defeated the royalists in the Battle of Pichincha and occupied Quito on May 25. The Peruvian contingent that participated in this battle was made up of 1,600 troops under the command of Colonel Andrés de Santa Cruz and joined the Colombian patriot troop in Saraguro, on February 9, 1822. This event is memorable, because for the first time they converged the two liberating currents, that of the North and that of the South. Later, General Simón Bolívar invaded Guayaquil, with the desire to annex it to Colombia, of which he was its undisputed leader. Both Bolívar and San Martín were convinced that the definition of American independence had to take place on the still-disputed Peruvian soil.

Guayaquil Conference[edit]

San Martín could not finish the war against the Spanish. Although the entire north of Peru had voluntarily joined the patriot cause, its central and southern parts remained under the control of viceregal troops. San Martín considered external military aid necessary and in pursuit of it he went to meet with Bolívar in Guayaquil. In what became known as the Guayaquil Conference, held between July 26 and 27, 1822, they discussed three important questions:

- The fate of Guayaquil, which, being Peruvian territory, was annexed by Bolívar to Colombia.

- The help that Bolívar had to provide for the common goal of the independence of Peru.

- The form of government that the nascent republics had to adopt.

The interview did not produce any concrete results. Regarding the first point, Bolívar had already decided that Guayaquil belonged to Colombia and did not admit any discussion on the matter. Regarding the second point, Bolívar offered to send a Colombian auxiliary force of 2,000 men to Peru, which San Martín considered insufficient. And regarding the third point, Bolívar was decidedly republican, thus opposing San Martín's monarchism. Disillusioned, San Martín returned to Peru, already convinced that he should withdraw to give way to Bolívar.

First Constituent Congress[edit]

Before the events of Guayaquil, San Martín had convened the First Constituent Congress of Peru, on May 1, 1822. 80 deputies were elected, and this legislature was solemnly installed on September 20, 1822. It was presided over by the clergyman Francisco Xavier de Luna Pizarro. As soon as this First Constituent Congress was installed, it approved a proposition that said: "...that the Constituent Congress of Peru is solemnly constituted and installed, sovereignty resides in the nation, and its exercise in the Congress that legitimately represents it."

After the installation and on the same date, this Congress offered General San Martín dictatorial powers, which he refused. The offer was changed to that of "Founder of the Freedom of Peru and Generalissimo of Arms" (Spanish: Fundador de la Libertad del Perú y Generalísimo de las Armas), a title that was accepted by San Martín, although in an honorary manner. His decision to retire was final.

Congress accepted San Martín's resignation and agreed with Arce's proposal, saying that "since Congress must retain as much authority as possible to enforce its determinations, and running the risk that a foreign Executive Branch, isolated and separated from it, although of its own making, may form an opposition party," it determined that Congress retain the Executive Power. It was also decided that it should be made up of three people. One of the deputies, José Faustino Sánchez Carrión, stated on that occasion: "Three do not unite to oppress. One's government is more effective if governing is treating the human race like beasts…" and he adds: "Freedom is my idol, as it is the people's. Without it I don't want anything; The presence of only one in command offers me the hated image of the King." And thus the Supreme Governing Junta was formed, made up of three congressmen.

- General José de La Mar, a native of Cuenca.

- Jurist and soldier Felipe Antonio Alvarado, a native of Río de la Plata.

- Count Manuel Salazar y Baquíjano, a nobleman from Lima.

Several declarations of this First Constituent Congress mark the end of monarchical efforts, such as the declaration of November 11, 1822 on the incompatibility of the Order of the Sun and the Titles of Castile with the form of the government of Peru and the declaration of the November 12 of the same year, disavowing commissioners García del Río and James Paroissien.

José de San Martín retired to Magdalena, where he had a country house. Accompanied by a small escort and an assistant, on the same night of his resignation, mounted on horseback, he headed to Ancón, north of Lima. At dawn on September 22, he embarked for Valparaíso aboard the brig Belgrano.

The First Constituent Congress promulgated on November 12, 1823, the First Political Constitution of the Republic, with a clear liberal tendency. It was an ephemeral Constitution; When General Simón Bolívar arrived in Peru, the Constituent Congress itself had to suspend its effects in order to give him dictatorial powers.

Government of the Supreme Governing Junta (1822–1823)[edit]

The primary mission of the Junta was to continue the fight against the royalists. Viceroy La Serna had more than 20,000 soldiers who occupied the territory between Cerro de Pasco and Upper Peru. San Martín had already foreseen that more forces were necessary to defeat the royalists, who had turned all that territory into a true bastion of his power. The help that Bolívar had offered to Peru to defeat the Spanish was still in progress. Indeed, during the Guayaquil meeting, Bolívar offered San Martín military aid to Peru, which materialized in July 1822, with the sending of troops under the command of Juan Paz del Castillo, but these were still insufficient. In September of that year, Bolívar offered another 4,000 soldiers, but the already installed junta only accepted the receipt of 4,000 rifles. Peru's relations with Colombia entered their most critical point due to the annexation of Guayaquil to Colombian territory. Added to this was the fact that Juan Paz del Castillo received instructions from his government not to commit his forces only in case success was guaranteed and only in northern Peru, so he came into conflict with the interests of Peru, which focused on attacking the royalists in the centre and south. Said Colombian officer returned to his homeland in January 1823, displeased at not being able to impose his conditions. Relations with Colombia cooled then, at the precise moments when the so-called First Intermedios campaign was being fought.

First Intermedios campaign[edit]

The Junta organized a military expedition against the Spanish who still dominated southern Peru. The Campaign of the Intermediate Ports took its name from the fact that the plan was to attack the Spanish from the southern coast located between the Peruvian ports of Ilo and Arica. This plan had been outlined by San Martín himself, but originally it contemplated, in addition to the attack from the southern Peruvian coast, a combined offensive by the Argentines through Upper Peru and the patriots from Lima through central Peru. However, the Junta could not obtain the support of the government of Buenos Aires, overwhelmed by internal difficulties, and did not grant the army that garrisoned Lima the necessary means to timely initiate an offensive into the central mountains. The departure of the Colombian Juan Paz del Castillo also influenced the paralysis of the preparations of the so-called Patriotic Army of the Centre. The campaign, commanded by the general Rudecindo Alvarado, ended in total failure as the complete plan was not followed and dynamism was not put into the actions, which gave time for the royalists to go on the defensive.

Alvarado arrived in Iquique where he had a detachment disembark to begin action on Upper Peru. Then he headed to Arica, where he remained without disembarking for three weeks, giving time for Viceroy La Serna, informed by his espionage service of the patriot presence, to order his lieutenants José de Canterac and Gerónimo Valdés to go with their forces to the threatened area. When at the end of December Alvarado landed in Arica and advanced on Moquegua, he encountered the royalist forces that occupied better positions. Valdés went out to meet him, fighting the battle of Torata. The royalist leader resisted for eight hours until Canterac came to his aid with his cavalry; Together they put the patriots to flight, thus achieving victory for the king's flag on January 19, 1823. Valdés, encouraged by his success, pursued Alvarado's troops, catching up with them and definitively defeating them in the Battle of Moquegua on January 21, 1823. The patriot troops, reduced to a quarter of their original number, had to hastily reembark and return to Callao with nearly 1,000 survivors.

From then on, the lyrics that the Spaniards spread from their camp located a short distance from Lima date back, in which they mocked the Congress:

Congress, how are we doing after the tris tras of Moquegua? From here to Lima there's a league. Are you going? Are you coming? Are we going?

After this military disaster, the Junta and Congress were tremendously discredited in the eyes of public opinion. It was feared that the royalist troops stationed in Jauja would go on the offensive and reconquer Lima.

Balconcillo mutiny[edit]

The patriotic officers in command of the troops that garrisoned Lima, fearing a Spanish offensive, signed a request before Congress, dated February 23, 1823 in Miraflores, invoking the designation of a single Supreme Chief "to order and be quickly obeyed”, replacing the collegiate body that made up the Junta. The name of the official indicated to assume the government was even suggested: Colonel José de la Riva Agüero.

The crisis deepened when another request was presented to Congress by the civic militias quartered in Bellavista and a third headed by Mariano Tramarría. On February 27, the troops mobilized from their cantonments to the Balconcillo hacienda, half a league from Lima, from where they demanded the dismissal of the Junta. These rebels were led by General Andrés de Santa Cruz. It was the first coup d'état in Peruvian republican history, known as the Balconcillo mutiny, which inaugurated the succession of de facto governments that marked the course of republican life.

Dissolution of the Junta[edit]

Faced with such pressure, that same day, Congress agreed to dismiss the Junta and temporarily entrust the highest magistracy to the highest ranking military leader, who was José Bernardo de Tagle y Portocarrero, 4th Marquess of Torre Tagle. On February 28, Congress ordered the release of General José de La Mar, who had been arrested at his home, and summoned General Andrés de Santa Cruz, who made an oral presentation of the position of the leaders and ended by saying that they obeyed the order of Congress but that if Riva-Agüero was not named President of the Republic, he and the military leaders would resign and leave the country. Given what was expressed by Santa Cruz, Congress appointed Riva-Agüero as President by 39 votes in favour of a total of 60. He was not assigned duties or deadlines. A few days later, on March 4, 1823, the same Congress promoted him to Grand Marshal and ordered that he use the two-color sash as the insignia of the executive power that he administered. Since then all the Presidents of Peru have worn this presidential sash.

Government of Riva Agüero (1823)[edit]

José de la Riva Agüero launched great efforts to put Peru in a position to finish the war of independence on its own. His governmental work took shape in the following points:

- He dedicated himself to the work of organising and improving the Peruvian Army, putting great effort into increasing its troops with Peruvian elements. He placed General Andrés de Santa Cruz in charge of him. He ordered Commander Antonio Gutiérrez de la Fuente to form reserve forces in the northern provinces, in Trujillo, also ordering Colonel Ramón Castilla to create the fourth Hussar Squadron.

- He formed the first Peruvian squadron, whose command he entrusted to Vice Admiral Martín Guise. He created the Naval School of Peru. He established a permanent blockade of the coast to defend it from royalist incursions.

- He collected the paper money issued under the Protectorate of Saint Martin and whose circulation was prohibited.

- He sent diplomatic missions to Colombia, Chile and the United Provinces of the Río de la Plata to request immediate help from these countries to consolidate the independence process. The help that Riva-Agüero most needed was that of Bolívar, appointing General Mariano Portocarrero as his Plenipotentiary Minister to Bolívar. Portocarrero agreed with Bolívar in Guayaquil to provide aid for 6,000 men, equipped and paid for by Peru, and in accordance with this agreement, the first Colombian troops began to arrive in Callao in April of 1823. Along with them, General Antonio José de Sucre arrived as Bolívar's Envoy Extraordinary, but whose true objective was to prepare the ground for Bolívar to be called to Peru. Riva-Agüero also sent the diplomat José de Larrea y Loredo to Chile, who managed to obtain a loan from the Chilean government and help in men and materials to continue the war against the Spanish. Before the United Provinces of the Río de la Plata he commissioned Vice Admiral Manuel Blanco Encalada to represent Peru, without positive results.

- Commissioners James Paroissien and Juan García del Río managed to contract with England a loan for £ 1,200,000, the first in the republican history of Peru. This allowed Riva-Agüero to have the necessary funds for his governmental work.

Second Intermedios campaign[edit]

Riva-Agüero undertook another campaign that targeted the Intermediate Ports, embarking his troops from May 14 to 25, 1823, heading to the southern ports, from where he planned to attack the Spanish who still dominated all of southern Peru. This expedition was commanded by General Andrés de Santa Cruz and the then Colonel Agustín Gamarra was the chief of staff. Santa Cruz promised to return victorious or dead. It was the first time that an army made up entirely of Peruvians was put into action. Santa Cruz landed his forces in Iquique, Arica and Pacocha and advanced on Upper Peru. The patriots initially won some victories. Gamarra occupied Oruro and Santa Cruz occupied La Paz, but the reaction of the royalists was immediate. Viceroy La Serna sent his general Gerónimo Valdés to attack Santa Cruz, resulting in the battle of Zepita of August 25, 1823, on the shores of Lake Titicaca. The patriots remained masters of the field, but without obtaining a decisive victory. Immediately afterwards, Santa Cruz ordered the withdrawal towards the coast, being closely pursued by the forces of La Serna and Valdés, who contemptuously called this campaign the "heel campaign" (Spanish: Campaña del talón), alluding to how close they were to the patriots who retreated, almost “on their heels.” Santa Cruz did not stop until he reached the port of Ilo where he embarked with 700 survivors. The campaign therefore ended in total failure for the patriots.

Dispute with Congress[edit]

When Lima was left unguarded, the royalist leader José de Canterac advanced from the mountains against the capital. Riva-Agüero then ordered the transfer of government agencies and troops to the Real Felipe Fortress, on June 16, 1823. On the 19th, Spanish forces regained control of Lima.

In Callao, discord broke out between Congress and Riva-Agüero. Congress resolved that the Executive and Legislative powers be transferred to Trujillo. It also created a military power that he entrusted to the Venezuelan general Antonio José de Sucre (who had arrived in Peru in May of that year, at the head of the first Colombian troops), and accredited a delegation to request the personal collaboration of Simón Bolívar in the war on June 19, 1823. Immediately, the same Congress granted Sucre powers equal to those of the President of the Republic for the duration of the crisis, and on June 23, it ordered that Riva-Agüero be exonerated from supreme command.

Riva-Agüero did not comply with this congressional provision and embarked to Trujillo with part of the authorities. He maintained his investiture as President, decreed the dissolution of Congress on July 19, 1823, and created a Senate made up of ten deputies. He formed troops and attempted to reinforce them with the remains of the Intermedios campaign. While in Lima, the Congress was again convened by the provisional president Torre Tagle, on August 6 of the same year.

Government of Torre Tagle (1823–1824)[edit]

Congress recognized José Bernardo de Tagle y Portocarrero, 4th Marquess of Torre Tagle, as President of the Republic, this being the second citizen to adopt this title, after Riva-Agüero. Anarchy therefore spread in Peru, as two parallel governments existed at the same time.

His governmental work took shape in the following points:

- He reinstated the Congress that had been dissolved by Riva-Agüero on August 6, 1823. Despite its defects, Congress then emerged as the sole representative of sovereignty and the sole source of legitimacy. It included personalities of the stature of José Faustino Sánchez Carrión, Toribio Rodríguez de Mendoza, Manuel Salazar y Baquíjano, José de La Mar, Hipólito Unanue, Justo Figuerola, among others. His immediate task was the culmination of his constituent work, that is, the text of what would be the first political charter of the Peruvian Republic.

- He agreed that Congress granted Bolívar military and political authority throughout the territory of the Republic, with great breadth of powers, under the name of Libertador. He had to come to an agreement with Bolívar in all cases that were his natural attribution and that were not in opposition to the powers granted to him (September 10, 1823). As a ridiculous compensation for this decrease in his power, Congress awarded Tagle a medal with the name "Restorer of Sovereign Representation."

- He promulgated the liberal Constitution of 1823 on November 12, 1823, the first that Peru had. It was divided into three sections dedicated to the Peruvian nation, territory, religion and citizenship; to the form of government and the powers that comprised it; and the means of preserving the government. One day before this promulgation, the same Congress declared that it was suspending compliance with the constitutional articles incompatible with the powers given to Bolívar. So, in practice, the Constitution of 1823 was not in force for a single day during Tagle's government. Only after the fall of the Bolivarian regime in 1827 was it restored, to last ephemerally, when it was replaced in 1828 by another Constitution.

The Peruvian Congress, following the recommendations of General Sucre, invited Bolívar to move to Peru "to consolidate independence." Bolívar embarked on the brig Chimborazo in Guayaquil, on August 7, 1823, arriving in Callao on September 1 of the same year. On September 10, the Congress of Lima granted him supreme military authority throughout the Republic. Torre Tagle was still president, but he had to agree on everything with Bolívar. The only obstacle for Bolívar was Riva-Agüero, who dominated northern Peru, with his capital in Trujillo. Riva-Agüero gave no sign of wanting to reach an agreement that would make possible the unification of all the patriot forces under the command of Bolívar, and rather wanted to reach an agreement with the royalists.

Bolívar himself opened the campaign against Riva-Agüero, marching north. But before the civil war broke out, Riva-Agüero was captured by his own officers led by Colonel Antonio Gutiérrez de la Fuente, who, disobeying the order to shoot him, banished him to Guayaquil on November 25, 1823. Bolívar entered Trujillo in December 1823 and thus dominated the political and military scene of Peru. He then headed back to Lima. On January 1, 1824, he was in Nepeña and Huarmey, from there he went to Pativilca where he fell ill with malaria.

Government of Simón Bolívar (1824–1826)[edit]

The royalists, aware of Bolívar's illness, took advantage of the situation and managed to get the patriotic troops (from the River Plate and Chile) who were garrisoning the Real Felipe Fortress in Callao, to mutiny, demanding accrued payments and other mistreatment. The mutineers managed to take the fort, freed the Spanish prisoners, gave them back their positions and hierarchies and together with them, they raised the Spanish flag, committing treason to the liberating cause. This act of sedition caused confusion in Lima (February 5, 1824). Faced with such a delicate situation, Congress gave a memorable decree on February 10 giving Bolívar full powers to face the danger, annulling the authority of Torre Tagle. Thus the Dictatorship was installed.

Canterac ordered the royalist generals José Ramón Rodil and Juan Antonio Monet to take advantage of this circumstance and take Lima. General Monet, from Jauja, and General Rodil, from Ica, met in Lurín, on February 27, 1824. The patriots of Lima were forced to abandon it, under the command of General Mariano Necochea, who together With 400 Montoneros on horseback, they were the last to withdraw on February 27. The royalists entered Lima on February 29 of the same year.

Bolívar, now recovered from his illness, faced with the news that came to him from Lima, began preparations for a retreat to Guayaquil, fearing the territorial loss of Colombia achieved in the southern campaigns. He set up his headquarters in Trujillo and received help from the Peruvians, both in money, supplies and resources of all kinds, as well as in combatants. Indeed, outside of his regular army, Bolívar had the valuable help of 10,000 Montoneros. This huge contingent of irregular soldiers was made up mainly of Indians recruited in the free provinces. Bolívar commissioned the leaders of the Montoneros to act on the following fronts: Francisco de Paula Otero, named general commander of the Montoneros of the mountains; Ignacio Ninavilca, of the Huarochirí area, who was later nominated as a representative before congress; Colonel Juan Francisco de Vidal, of La Oroya; Major Vicente Suárez, of Canta; and Commander María Fresco, in charge of Junín.

Royalist rupture[edit]

But Bolívar's salvation came from the rebellion or uprising of Pedro Antonio Olañeta, military chief of Upper Peru, which involved the entire Upper Peruvian royalist army, on January 22, 1824, against the authority of Viceroy La Serna, causing a domestic war that dismantled the Spanish defensive system. It was the Olañeta rebellion, the consequent internal confrontation between the monarchists and the detachment of Valdés' division from the main royal army that allowed Bolívar to reorganize and recover the initiative, lost by the decision of Viceroy La Serna to abandon the persecution against Bolívar through the north, and direct his main forces against Olañeta, trying to preserve Upper Peru.

Junín Campaign[edit]

While Bolívar prepared everything related to the final campaign of independence from his headquarters in Trujillo, Sucre toured the terrain in the mountains, and with the protection of the Montoneros he drew up sketches and plans of the territory that would inevitably be the scene of the war. The spy service was improved, the fields and forage for horses were prepared, and food depots were established along the route that the liberating army had to travel.

Both soldiers and horses trained to face the rigors of the climate. The army was concentrated between Cajamarca and Huaraz. The Peruvian division was commanded by Marshal José de La Mar, while the Colombians, reinforced with new troops arrived from Colombia under the command of generals Jacinto Lara and José María Córdova, were led by Sucre.

Preliminary movements[edit]

Bolívar managed to form an army of about 10,000 men, but the viceregal forces numbered about 18,000. Olañeta's revolt at the head of 4,000 soldiers forced La Serna to send General Valdés to fight him with the royalist forces stationed in Puno. This situation motivated Bolívar to immediately open a campaign against the closest royalist army, which was that of José de Canterac, which was stationed between Jauja and Huancayo. The liberating army advanced to the Callejón de Huaylas. In the month of May, it continued its march towards the central mountains, effectively supported by the Montoneras led by Marcelino Carreño. It arrived in Huánuco on June 26, 1824 and continued to Cerro de Pasco.

Between July 31 and August 10, 1824, the patriot army was concentrated in the region of Quillota, Rancas and Sacramento. They numbered in total about 8,000 men. On August 2, Bolívar reviewed his army on the Rancas plain, 36 km from Cerro de Pasco. After the review, he harangued his soldiers displaying overwhelming eloquence, a virtue that was complemented by his military talent:

Soldiers! You are going to complete the greatest work that heaven has entrusted to men: that of saving an entire world from slavery.

Soldiers! The enemies you are going to destroy boast of fourteen years of triumphs. They, then, will be worthy of measuring their weapons with yours that have shined in a thousand battles.

Soldiers! Peru and all of America await peace from you, the daughter of victory, and even liberal Europe contemplates you with charm because the freedom of the New World is the hope of the Universe. Will you outwit her? No. No. You are invincible.

— Simón Bolívar

The liberating army continued its advance south, bordering Lake Junín. Canterac found out late about the patriot advance because he did not have a good spy service and decided to go out to meet the adversary, leaving Jauja on August 10 with 7,000 infantry men and 1,300 cavalry, heading towards Cerro de Pasco. Upon arriving there, he was surprised to learn that Bolívar was marching towards Jauja on the left side of the lake, to block his path. Fearful that the patriots would cut off his retreat to their bases, Canterac immediately ordered a countermarch.

On August 5, Canterac was in Carhuamayo, on the eastern margin of the lake, while Bolívar was at more or less the same height, on the western margin of the lake. The Spaniard ordered to speed up the retreat to get ahead of the Liberator. At dawn on August 6, both adversaries converged at the southern end of the lake on the Pueblo de Reyes. The lighter royalist infantry crossed the pampa called Junín, which is located south of said city, two hours before the patriots appeared.

Battle of Junín[edit]

It was two in the afternoon on August 6, 1824 when Bolívar arrived at the pampa of Junín and observed that the royalist infantry had already passed and that only the royalist cavalry, which was going to the rear, was in sight, in the middle of an immense cloud of dust. For his part, the patriot cavalry, 900 strong, which was coming at the vanguard of his army, was converging at that moment through the Chacamarca ravine, while his infantry was still distant, about 5 km to the north.

Bolívar then wanted to prevent Canterac from fleeing and ordered his cavalry to attack the royalist army, to give time for the patriot infantry to arrive. From the heights of the Chacamarca ravine, the patriot squads launched onto the plain, under the command of General Mariano Necochea.

Canterac, confident in the numerical superiority of his cavalry, ordered them to stop the patriots, putting himself in the lead, while his infantry continued their march south. The patriots could not fully deploy their squadrons due to the poor terrain, which was a narrow space between a hill and a swamp, while the royalist cavalry, in more favorable terrain, deployed their lines and attacked as well. At four in the afternoon the violent clash took place. The patriots began to retreat, pursued by the royalists. Necochea himself was wounded seven times and everything indicated that the skirmish would culminate in defeat for the patriots. It was then that the Peruvian Hussar squadron, which was in reserve under the command of lieutenant colonel Manuel Isidoro Suárez, received the order to charge the royalists from behind. It was the assistant of the first squad, Major José Andrés Rázuri, who transmitted that order, supposedly coming from Bolívar himself, which was not true. Rázuri, a native of San Pedro de Lloc, changed the original order, which was to retreat; and this bold decision was the one that changed history, exchanging a certain patriotic defeat for a decisive victory.

The charge of the Peruvian Hussars disoriented the royalists and gave time for the persecuted patriots to rally and return to the fight. After forty-five minutes of fierce combat with only bladed weapons (sword and spear), the patriots were victorious. Bolívar, who had already taken defeat for granted and had left the field, suddenly received the report sent by Guillermo Miller announcing victory. The Liberator burst into joy and from then on decided to rename the Hussars of Peru as the Hussars of Junín.

Ayacucho Campaign[edit]

Canterac, after the battle of Junín, pursued by the Montoneros of Colonels Marcelino Carreño, Otero, Terreros, by Commander Peñaloza, by Major Astete, headed south along the banks of the Mantaro River. He crossed the Izcuchaca bridge, and headed along the Pampas River to Cuzco, where Viceroy La Serna was waiting for him. In his retreat, General Canterac lost 3,000 soldiers, including stragglers, deserters, sick and lost. In addition, warehouses, weapons and ammunition were abandoned.

While General Canterac continued his escape south towards Cuzco, Bolívar's itinerary was as follows: on August 7, 1824, he celebrated the victory in the Pueblo de Reyes, on August 8 he was in Tarma, on August 12 in Jauja, on August 14 in Huancayo and on August 24 in Huamanga. He reached Andahuaylas from where he returned on October 6. He ordered Carreño to permanently harass Canterac. He delegated command of the patriot army to General Antonio José de Sucre. With his headquarters in Jauja, he entrusted General Andrés de Santa Cruz with the leadership of all the Montoneros of the central mountain range. Then, accompanied only by his escort, he headed to Lima. On August 15, in Huamanga, he had appointed his ministerial cabinet which consisted of: José Faustino Sánchez Carrión, Minister of Government and Foreign Affairs; Colonel Tomás de Heres, Minister of War and Navy and Hipólito Unanue, Minister of Finance.

Bolívar arrived in Chancay in the month of November 1824, entering Lima on December 7 of that year. He immediately ordered the siege of Callao with the objective of surrendering Rodil's troops, who were stationed in the Real Felipe Fortress.

Meanwhile, the situation in the royalist army is described by General García Camba:

This brilliant and spirited army at the beginning of August was now in the most lamentable state. It had not only seen the well-deserved fame of his cavalry demolished in the devastated fields of Junín; Not only had it lost with astonishing speed a large part of its provinces of Tarma and Lima, the entire provinces of Huancavelica and Huamanga, part of Cuzco, all its warehouses, many weapons, ammunition, equipment and, above all, 3,000 infantry due to desertion, but in just over a month it had reached a degree of moral despondency that was barely conceivable... Carreño covered the country between Abancay and Apurímac with all the Montoneros.

— From Memorias para la historia de las armas españolas en el Perú: 1809 – 1812

General Sucre prepared for the final campaign. While in Andahuaylas, he gathered his General Staff in response to reports that the royalist Gerónimo Valdés had arrived in Cuzco with a strong contingent, placing himself under the orders of Viceroy La Serna. Sucre, on an inspection, arrived at Mamara. In this town he sent an advance party under the command of General Miller to spy on the enemy. Miller returned on 30 October and reported that the royalists were only 36 km away. Sucre then ordered the retreat to the northwest.

The contingent and weapons of both armies[edit]

La Serna, convinced of the proximity of the decisive battle, had formed a powerful army with 10 thousand soldiers, most of them “Quechua-speaking” mestizos, Creoles, blacks, browns, and Indian carriers. This army had 14 infantry battalions, 2 cavalry brigades and 14 artillery pieces. La Serna commanded the cavalry. Valdés was at the forefront with an infantry division. The other two were commanded by Canterac and Monet. The united patriot army had about 7,000 soldiers, plus the Montoneros. The regular army was dispersed and the Montoneros carried out military tasks of "cover, liaison and support."

March towards Ayacucho[edit]

Given the presence of Valdés near Andahuaylas, Sucre withdrew his army towards Huamanga, along the banks of the Pampas River, regrouping his forces, without any rush. On the contrary, La Serna, who had ordered his troops to march on forced marches to gain positions, arrived at Huamanga on November 16, 1824.

On November 24, both armies marched on both banks of the Pampas River, keeping each other in sight. From that day on, they never lost sight of each other. The patriot troops went from town to town, encouraged by the Montoneros, and were welcomed and helped effusively by its inhabitants. On the other hand, the royalist troops were avoiding all contact with the residents of the towns through which they passed, thus ensuring the disbandment of the troops. General Guillermo Miller in his Memoirs stated:

At any point where they stopped, the corps camped in column and placed a circle of sentinels of the most trusted soldiers around them; In addition to these sentinels, a large number of officers were always on duty, and no soldier could leave their line, under any pretext whatsoever. For the same reason the viceroy was very opposed to sending parties in search of cattle, because on such occasions desertion was certain. The consequence of this system was that during the rapid advance of the royalists they suffered much more from lack of provisions than the patriots, so much so that on December 3 they were forced to eat horse, mule and donkey meat.

Battle of Corpahuaico[edit]

On December 3, 1824, in the vicinity of Corpahuaico (or Matará), there was a skirmish between the rearguards, with military consequences that were not favorable for the patriots. In the patriot forces under the command of General Guillermo Miller, 300 deaths were counted; while in the royalist sector, under the orders of General Valdés, 30 dead were found. In addition, the patriots lost a good part of their fleet and artillery.

But according to experts, from a strategic point of view this result was beneficial for the patriots, because the defeat encouraged them, while the moral crisis among the royalists deepened, to such an extent that that same day 15 soldiers, who had been recruited by Valdez In Upper Peru, joined the ranks of Sucre and informed him of the moral weakening of the enemy ranks. "They are almost like prisoners," they said.

Preliminary movements[edit]

Since December 4, both armies marched separated by an abyss. The patriots passed through Huaychao on the 5th, and on the 6th their outposts arrived a little further north of La Quinua. The royalists took the Huanta route, through Paccaicasa. On the 6th, they camped in Huamanguilla; The viceroy's idea was to cut off all retreat to Sucre. On December 7, each army prepared for battle, trying to find the best location. On the 8th there were some clashes between patrols.

Battle and Capitulation of Ayacucho[edit]

Ready to engage in the final battle, the royalists occupied the slopes of the Condorcunca hill and the patriots deployed in the Pampa de la Quinua. The former had 9,310 men and the latter had 5,580. When the battle took place on December 9, the independentist forces were led by Sucre. Viceroy José de la Serna was wounded, and after the battle second commander-in-chief José de Canterac signed the final capitulation of the Royalist army. Although its signing is dated December 9, 1824, the reality is that the deliberations lasted two days in total. It dealt with the formation of mixed committees that would work to transfer all the remaning assets of the Spanish Army, while also providing protection for the remaining Spanish troops, providing financial compensation and allowing their incorporation to the Peruvian Army if desired. The most notable consequences were:

- The complete independence of Peru and Spanish America.

- The disappearance of the royalist army, which had remained for 14 years as a powerful wedge, pointing and threatening the recent and precarious independence of the American countries that did so before 1821.

- Spain, finally, despite having been defeated, managed to have "war expenses" recognised (the so-called Independence debt, which Peru would never pay).

Olañeta in Upper Peru[edit]

After the capitulation was signed, the royalist forces that occupied the south of Peruvian territory, between Cuzco, Arequipa and Puno, surrendered to the independence forces. On December 14, 1824, General Sucre entered Cuzco. Francisco de Paula Otero, first, and Lara, later, took Arequipa.

General Pedro Antonio Olañeta, who did not accept the Capitulation and announced his desire to continue fighting under the flag of Spain, remained in Upper Peru. Sucre then opened a campaign in said territory, counting on the collaboration of General Juan Antonio Álvarez de Arenales who, in his capacity as governor of the Argentine province of Salta, prepared to attack this region. However, there was no need for further fighting, since in the battle of Tumusla, the royalist officers themselves killed Olañeta on April 2, 1825. Thus ended the independence campaign in Upper Peru.

Rodil in Callao[edit]

Another Spanish soldier who refused to abide by the terms of the capitulation was José Ramón Rodil who, in command of the Real Felipe Fortress in Callao (which had returned to royalist power in February 1824), remained stubbornly loyal to the king of Spain. Bolívar accentuated the siege of said bastion, cutting off all kinds of supplies, both by land and by sea. After months of stubborn resistance, only on January 23, 1826, Rodil agreed to capitulate, handing over the Fortress to the Peruvian government. Of the 6,000 refugees, including military and civilians, 2,400 left after the surrender. Of that group, only 400 were military personnel. General Rodil, the last champion of the royalists in South America, embarked for Spain on the English frigate Briton.

Prolongation of Bolívar's government[edit]

After the victory of Ayacucho, Bolívar convened the Peruvian Congress, which had been in recess since the previous year. The meeting of the congressmen took place on February 10, 1825 and before them, Bolívar resigned from command (or at least pretended to do so). Resignation that was not accepted, since the parliamentarians considered that his work was not finished, as a royalist focus still remained in Callao. So Congress decided to extend his command, after which he dissolved himself on March 10, 1825.

In general, the extension of the Bolivarian Dictatorship was not well received by citizens. They considered that Bolívar's mission had ended with Ayacucho and that it was up to the Peruvians to take charge of the government. But a sector of citizens, led by conservative politicians, argued that a strong government was necessary to prevent the nascent republic from falling into anarchy. Bolívar was not permanently in power, as he left it in charge of the President of the Government Council, from February 24, 1825, although he continued to issue decrees, until September 3, 1826, when he returned to Colombia. His authority was nominally maintained until January 27, 1827, when his influence in Peru ended.

Collaborating with Bolívar as ministers were: José Faustino Sánchez Carrión, José María Pando, Hipólito Unanue, among others. Another of his collaborators was the jurist Manuel Lorenzo de Vidaurre, who later became his opponent.

A dark episode that occurred at the beginning of 1825 was the murder of Bernardo de Monteagudo, the former minister of San Martín, who had returned to Peru to enter the service of Bolívar. One version attributed the intellectual authorship of said crime to Faustino Sánchez Carrión, who also died months later, apparently a victim of an illness, although there were some who attributed it to poisoning.

Simón Bolívar left Lima on April 15, 1825, beginning a journey through the southern departments of Peru, passing through Ica, Arequipa, Cuzco and Puno, from where he entered Upper Peru in August of that year. Additionally, through a law promulgated on February 25, 1825, the flag and Coat of arms of Peru were definitively established. The author of the Shield was the representative for Lima and President of Congress, José Gregorio Paredes.

Creation of Bolivia[edit]

Once the independence of Upper Peru was achieved in 1825, this region was left with the dilemma of joining the United Provinces of Río de la Plata (since it had been part of the Viceroyalty of Río de la Plata) or maintaining its adhesion to Peru (since it had returned to the Viceroyalty of Peru in 1809, by the work of Viceroy José Fernando de Abascal). The supporters for its annexation to one or the other were numerous. A third position then emerged that embodied the idea that Upper Peru should form a new republic.

In this situation, the Peruvian Congress, in an assembly on February 23, 1825, agreed to allow the Upper Peruvians to resolve what was convenient. The Congress of Río de la Plata did the same. Marshal Antonio José de Sucre, who had assumed the government in Upper Peru, convened a Congress in Chuquisaca, beginning deliberations on July 10, 1825. On August 6 of the same year, said Congress almost unanimously agreed on independence. of Upper Peru, which from now on would be called the Republic of Bolívar. The Liberator, who arrived shortly after in triumph, approved the birth of the new State and at the request of the Upper Peruvians themselves, began to write their first Constitution, the same one that he submitted for approval to Congress. The name of the brand new republic was definitively established as "Bolivia." The Constitution, called the "Lifetime Constitution" as it contemplated a President for life (who had to be Bolívar himself), was sanctioned on November 6, 1826 and Sucre was elected as the first President of the Republic, a position he accepted for only two years.

The failed Congress of 1826[edit]

On May 20, 1826, Bolívar issued a decree in Arequipa calling for a General Congress, which would meet in Lima on February 10, 1826, that is, exactly one year after the extension of his dictatorial powers. His intention was for this Congress to approve for Peru the same Constitution that was being discussed in Bolivia. The election of members of Congress corresponded, as established in the Constitution of 1823, to the Electoral Colleges of the provinces, made up of the electors of the parishes. Despite pressure from the government, some liberal and anti-Bolivarian deputies were elected, among which the representatives of Arequipa, the clerics Francisco Xavier de Luna Pizarro and Francisco de Paula González Vigil, stood out. This provoked the anger of Bolívar, who in a letter addressed to Antonio Gutiérrez de la Fuente (then prefect of Arequipa) complained about the "damned deputies" that he had sent to his jurisdiction, asking him to do something to change them. Pressured by Bolívar's reaction, the Government Council ignored the credentials of those deputies, thus amputating the liberal minority.

Finally, the Congress did not meet and only remained in the preparatory meetings, since the same deputies asked Bolívar to postpone the call until the following year. Bolívar accepted with pleasure, saying that he preferred the opinion of the people to the opinion of the wise, regarding the approval of the Constitution.

The Constitution of 1826[edit]

The so-called Life Constitution written by Bolívar for Bolivia was, in reality, an adaptation, with some amendments, of the Napoleonic Constitution of the Year VIII. It recognized the division of four powers: Executive, Legislative, Judicial and Electoral. The Executive was made up of a president for life with the power to appoint his successor; a vice president and three ministers. The Legislature resided in three chambers: tribunes, senators and censors. The Judicial Power was exercised by the Supreme Court and other courts of justice. The Electoral, would be composed of electors appointed by citizens in office.

This Political Charter was also submitted to Peru, but as the Congress of 1826 was unable to meet, its approval was submitted to the Electoral Colleges of the Republic, which did so, except for that of Tarapacá.

Bolívar's federative plans[edit]

Bolívar's wanted to reunite all the Spanish American States in a single great confederation, for which he convened the Congress of Panama that was installed on June 22, 1826. However, this first step to achieve American unity It failed miserably. Then, upon seeing himself contrasted by reality, Bolívar limited himself to his minimum plan, which was to reunite only the towns liberated by him, for which he outlined two plans, namely:

- Peru–Bolivian Federation: In reality, the constitution to be sworn in both Bolivia and Peru, was nothing more than a step to achieve the federation of both peoples. Previously, in mid-1826, Peru had sent Ignacio Ortiz de Zevallos to Bolivia with the task of signing the federation treaty, which was carried out on December 31 of the same year, with the name of the Bolivian Federation, which would have Bolívar as Lifetime Head of State and a General Congress with nine deputies from each State. It was also agreed to manage the inclusion of Colombia in the Federation. This treaty was not approved by the Peruvian Congress.

- Federation of the Andes: Although he did not specify this project well, Bolívar's evident dream was to reunite all the peoples he had liberated in a single state of which he He would be supreme ruler for life. This project also generated strong resistance and ended up failing when Colombia refused to approve the Lifetime Constitution and, consequently, to join the federation.

Oppposition to Bolívar[edit]

The most bitter opponents of Bolívar's dictatorship were the Peruvian liberals, one of whose leaders was the clergyman Luna Pizarro, who was exiled to Chile. In general, a reaction was unleashed in the country against him and against the Colombian troops, which was most visible among the former supporters of Riva-Agüero and the River Plate officers who had come with San Martín. It was no wonder, since the Colombians acted as occupation troops, committing outrages and looting against the population, added to the contempt with which they treated their Peruvian counterparts in the army. The discontent among the Peruvian troops was evident with the uprising of two squadrons of the Húsares de Junín regiment, in Huancayo, which ended with the execution of Lieutenant Silva; and with a conspiracy in Lima, which culminated in the execution of Lieutenant Aristizabal.

A sad event further increased the animosity towards Bolívar: the execution of Juan de Berindoaga y Palomares, a nobleman from Lima, unjustly accused of treason. Bolívar turned a deaf ear to the requests for forgiveness for Berindoaga, allowing his execution, which took place in the main square of Lima, on April 15, 1826. By appearing, Bolívar wanted with this act to punish the city's aristocracy, which was disaffected to him.

The opposition even extended to his homeland, where the guerrilla General José Antonio Páez revolted and proclaimed the separation and autonomy of the State of Venezuela. In Colombia the movement was similar, since Vice President Francisco de Paula Santander opposed the approval of the Lifetime Constitution and the federation plans. All this convinced the Liberator to withdraw from Peru and return to his homeland.

Decay of Bolivarian influence[edit]

On September 1, 1826, the same day that the third anniversary of his arrival in Peru was celebrated, Bolívar announced his definitive retirement, but at the insistent request of some ladies of Lima's society, he promised to stay, but on the 3rd of that month, he embarked on the brig Congreso, heading to Colombia, where he calmed things down, although for a short time.

With the withdrawal of Bolívar from Peru, the Bolivarian influence in this country did not end, since the Government Council chaired by General Andrés de Santa Cruz and supported by the Colombian forces under the command of General Jacinto Lara remained in supreme command. The fundamental mission of this Council, commissioned by Bolívar, was the promulgation of the Life Constitution.

On December 9, 1826, commemorating the second anniversary of the battle of Ayacucho, the so-called Life Constitution was solemnly sworn in both republics, Peru and Bolivia, as the Fundamental Law for the two countries, at whose head was the supreme figure of the Liberator, as ruler for life. In Lima the ceremony was opaque, amidst indifference and popular rejection. It is said that coins were thrown at those present, forcing them to shout "Long live the Constitution! Long live the President for life!" But some mockingly responded: "Long live money!"

End of Bolivarian influence[edit]

The opposition to the Bolivarian regime became stronger and more insistent every day due, mainly, to the action of the liberals. In the midst of this heated atmosphere, the same Colombian soldiers stationed in Lima, dissatisfied with the non-payment of their payments, mutinied on January 26, 1827, arresting Lara and other officers. This was taken advantage of by the Peruvian liberals led by Manuel Lorenzo de Vidaurre and Francisco Javier Mariátegui y Tellería, to take to the streets, inciting citizens to gather in the Open Cabildo to speak out against the life-long regime. The Cabildo, meeting on the 27th, took transcendent measures: it abolished the Lifetime Constitution (considering that it had been approved illegally by the electoral colleges, since they lacked the powers to do so), restored the Constitution of 1823 and agreed to call Santa Cruz, who was in Chorrillos, to take charge of the new government, with the demand that a Constituent Congress be convened within three months, which should elect the president of Peru and sanction a new Constitution. Santa Cruz promised so and took over the Peruvian government.

On January 30, 1827, General Jacinto Lara and the other Colombian leaders embarked for their homeland. In the month of March the rest of his troops did so. The Bolivarian influence in Peru thus came to an end.

Government of the Government Junta (1827)[edit]

A Government Board was installed, chaired by Andrés de Santa Cruz and made up of Manuel Lorenzo de Vidaurre, José de Morales y Ugalde, José María Galdeano y Mendoza and General Juan Salazar.

In compliance with the act of the Cabildo, Santa Cruz decreed on February 28, 1827, the convocation of a General Constituent Congress, in accordance with the constitutional letter of 1823, and whose mission would be to decide on the Constitution to be implemented, as well as the election of the President of the Republic. The call was carried out without difficulties, since Lima's pronouncement was peacefully supported in the rest of the country and the Colombian troops withdrew in the same way, back to their homeland.

Second Constituent Congress[edit]

The General Constituent Congress of Peru (the second in Peruvian republican history) was established on June 4, 1827, with 83 deputies elected by provinces, including Maynas (territory that Bolívar already claimed as part of Colombia at that time). Its first president was the liberal cleric Francisco Xavier de Luna Pizarro. In harmony with the decree that gave rise to it, this Congress repealed the Lifetime Constitution, partially replaced the Constitution of 1823 and began the discussion of a new political charter.

Election of José de la Mar[edit]

On June 9, the same day that Congress was installed, it approved a law by which it assumed the power to elect the President and the Vice President of the Republic, properly and not provisionally, since, according to its point of view, This was convenient for the security of the Republic. Luna Pizarro promoted the candidacy of Marshal José de La Mar, since he saw him as a suitable soldier for the republican government, as he was a person disaffected to militarism and leadership. La Mar had been elected deputy for Huaylas, but he was then in Guayaquil, as Political and Military Chief of said place (belonging to Colombia). Another group of deputies sponsored the candidacy of General Santa Cruz. But surprisingly, Luna Pizarro announced that that same day, June 9, the election would be held in a permanent session. La Mar triumphed with 58 votes, while Santa Cruz obtained 29. The latter was very upset with this result, which he considered illegal, thus becoming an opponent of the new government.

Government of La Mar (1827–1829)[edit]

La Mar, who was in Guayaquil, was informed of his choice, and then had to leave for Peru. It is said that he did it unwillingly, since he detested power; although possibly also due to his delicate health (he apparently suffered from liver disease). While his arrival lasted, Vice President Manuel Salazar y Baquíjano assumed interim command. On August 22, La Mar assumed his duties as Constitutional President of Peru.

La Mar's government was the first in Peru free of all foreign influence. From his first months, he had to put down three conspiracies:

- The first (December 1827), where the jurist Manuel Lorenzo de Vidaurre] (one of the supporters of Santa Cruz's candidacy) and the guerrilla Ignacio Ninavilca appeared involved.

- The second, promoted by Colonel Alejandro Huavique (April 23, 1828), was put down by the then sergeant major Felipe Santiago Salaverry, who killed the conspirator.

- The third (May 1828) gave rise to the dispersion of numerous officers in remote provincial garrisons.

These conspiracies were attributed to the intrigues of Santa Cruz, who was removed from the country and appointed plenipotentiary minister in Chile]. But it has been said that all these plots were nothing more than episodes of a vaster and deeper conspiracy, in which, in addition to Santa Cruz, the generals Agustín Gamarra (prefect of Cuzco) and Antonio Gutiérrez de la Fuente (prefect of Arequipa). These formed a kind of triumvirate, whose purpose was the fall of La Mar, a goal that they momentarily postponed, as a result of the conflicts with Bolivia and Colombia. Shortly after, Santa Cruz was named President of Bolivia, where he left, with prior authorization from the Peruvian government. In that country, Santa Cruz would carry out great administrative work, although he continued to intrigue against the Peruvian government. Already at that time he had in mind his plan for a Peru-Bolivian Federation, which years later he would make a reality.

As if that were not enough, La Mar also had to face a dangerous uprising by the Iquichans, loyalist Indians from Huanta Province under the leadership of Antonio Huachaca. They were still fighting for the king of Spain and on November 12, 1827 they attacked and took Huanta. Then, they advanced menacingly on Huamanga but were contained, and after a bloody campaign they were finally subdued.

Important works and events[edit]

First budget outline[edit]

The Minister in charge of Finance, José de Morales y Ugalde, presented to Congress an extensive report of everything done within his branch in the past government and a list of public receipts and expenses in 1827. The calculated income was 5,203,000 pesos and expenses of 5,152,000, giving a balance or surplus of 51,000 pesos, but this budget was not approved by Congress.

Constitution of 1828[edit]

The Constituent Congress gave the liberal Constitution of 1828, the second that the Republic of Peru had, whose promulgation and public oath was scheduled for April 5, 1828, which had to be postponed until the 18th of that month, due to having On March 30, a tremendous earthquake occurred in Lima that left the city almost in ruins. And although its bases were taken from the Constitution of 1823, it was enriched with norms that experience advised to include.

- In civil matters, it put an end to certain remnants of colonial life, namely: hereditary employments, estates, ties and privileges. Torture and infamous punishments were abolished and there was only the death penalty in cases of qualified homicide.

- Politically, he established: the indirect election of the president and vice president, for a four-year period, immediately renewable; chambers of senators and deputies, whose renewal would be carried out every two years by thirds and halves, respectively; creation of a Council of State, which was charged with the mission of observing and advising the executive branch; creation of Departmental Boards, as a means of satisfying and mitigating federalist tendencies. But a very important provision was the authorization to the President of the Republic to suspend constitutional guarantees and vest himself with extraordinary powers, for a certain period of time and with the responsibility of informing Congress about the measures adopted during the exercise of said powers.

- He offered the promotion of industries and education, the production of statistics, the civilization of indigenous people and support for immigration, among other good intentions that little or nothing would come to fruition.

War with Bolivia[edit]

Bolivia was still under Colombian orbit, with Marshal Sucre at the head as President. At that time, several rebel movements took place in that country, in one of which Sucre himself was wounded in the head and right arm, managing to painfully flee to take refuge in the presidential palace. Forced by circumstances, Sucre had to delegate power to its President of the Council of Ministers, General José María Pérez de Urdininea. Gamarra, who had the Southern Peruvian army under his command and without the authorization of the Peruvian Congress, invaded Bolivia on May 1, 1828, with the manifest intention of saving said country from the threat of anarchy and protecting the life of Sucre, although his true intention was to expel the Colombians and put an end to the Bolivarian predominance in that country. After a triumphant walk through Bolivian territory, with hardly any resistance, he signed the Treaty of Piquiza with the government of Urdininea on July 6, 1828, in which it was agreed, among other things, the withdrawal of the Colombian troops from Bolivia and the resignation of the presidency by Sucre. This fact was very important for Peru, since it eliminated a dangerous front in the face of the imminent war against Colombia.

War with Colombia[edit]

The biggest international problem that La Mar had to face was precisely the war with Colombia, headed by Bolívar. Relations had already deteriorated as a result of the territorial dispute, but the abandonment of the previous constitution and the events in Bolivia (as well as the role of the printed press of both countries) made things worse. Bolívar declared war on Peru on July 3, 1828, and La Mar responded by mobilising the Army and the Navy, leaving Manuel Salazar y Baquíjano in charge of Lima. While the maritime campaign was a success for Peru, the land campaign of both states lost its momentum around the time of the Battle of Tarqui, and a treaty led to Peruvian troops retreating from the territories they occupied, meaning Guayaquil and Loja, with Colombia implicitly recognising Peruvian sovereignty over Tumbes, Jaén and Maynas.

After the treaty was signed, an error on Sucre's part led to controversy: he had ordered that a monument be erected at Tarqui which stated that an army of 8,000 Peruvians who "invaded the land of their liberators" was defeated at the site. La Mar protested this by stating that the total number of troops was 4,500, while the troops at Tarqui were the vanguard, numbered at 1,000 men. He also criticised the language of the monument, highlighting the Peruvian efforts at Junín and Ayacucho in response to the alleged distaste that Peru had showed to its "liberators," and ultimately criticised the execution of Peruvian troops by Colombian officers, who also forcibly recruited others. As a consequence of the controversy, La Mar suspended the agreement until the issue was properly addressed.

While La Mar was willing to continue the conflict, a group of his own men arrested him in Piura during the night of June 7, 1829. These soldiers carried a letter from Gamarra to La Mar, where he asked for his resignation. La Mar refused to do so, and he was immediately transferred to the port of Paita, where at dawn on the 9th he was embarked along with Colonel Pedro Pablo Bermúdez and six black slaves, on a miserable schooner called "Las Mercedes", bound for Costa Rica, where he would die on October 11, 1830.

The reasons that Gamarra argued for carrying out this coup d'état were that La Mar was a "foreigner" and that his election by Congress had arisen from an arrangement hatched by Luna Pizarro (which is debatable). In Lima, General Antonio Gutiérrez de la Fuente, an ally of Gamarra, was in charge of overthrowing Salazar, assuming power temporarily, starting on June 6, 1829. But he did not want to retain power and he resigned before Congress on September 1 of the same year.

First Government of Gamarra (1829–1833)[edit]

On September 1, 1829, Congress appointed Marshal Agustín Gamarra as Provisional President of the Republic and Antonio Gutiérrez de la Fuente as Vice President. The first popular elections in Peru were then called. Gamarra obtained more than the absolute majority of the provincial electoral colleges required by the Constitution and was proclaimed Constitutional President by Congress on December 19, 1829.

Conservative authoritarianism[edit]

Gamarra's government wanted to be the opposite of La Mar's, which had been a constitutionalist effort. Gamarra left aside the Constitution of 1828, since he did not satisfy it due to the limitations it established for the Executive Branch. He established an authoritarian and conservative government. He had as advisors the most renowned representatives of Peruvian conservatism, among them the costumbrista writer Felipe Pardo y Aliaga, politician, jurist and writer José María Pando, orator and jurist Andrés Martínez de Orihuela, and the then colonel Manuel Ignacio de Vivanco.

Gamarra barely managed to complete his constitutional period. A total of 17 rebellions and conspiracies have been recorded that occurred during this period, among them the rebellion of Gregorio Escobedo in Cuzco, on August 26, 1830; the uprising of Captain Felipe Rossel in Lima on March 18, 1832; the rebellions of Felipe Santiago Salaverry in Chachapoyas on September 13, 1833; and that in Cajamarca on October 26, 1833. Gamarra had to be absent from the capital several times to quell these uprisings that occurred in the provinces. During his absence, he left the government in the hands of the vice president or a government official.

The Minister of Government, Manuel Lorenzo de Vidaurre, published a manifesto, censuring the attitude of the opponents of the regime, a document that ended with the words: "Order must reign. If necessary, the laws will be silenced to maintain the laws."

As time passed, liberal opposition to the government grew stronger and members of Congress made their protest felt. It was Francisco de Paula González Vigil, a priest from Tacna, who made the most severe criticism of Gamarra's authoritarian regime, culminating his argument with the famous words: "I must accuse, I accuse." In his eloquent speech, Vigil denounced the illegal acts and arbitrariness that the Gamarra regime had incurred. With these accusations, the government discredited itself even further. Congress adjourned at the end of 1832.

Interim leaders[edit]

Several people held interim command during Gamarra's first government.

The first of them was Vice President Antonio Gutiérrez de la Fuente, who took charge when Gamarra left to suppress the rebellion in Cuzco. La Fuente also manifested his authoritarian character and began to earn the enmity of the Lima political leadership, with a riot finally breaking out in Lima on April 16, 1831, promoted by Gamarra's wife, Francisca Zubiaga y Bernales, as a result of the controversy surrounding the monopoly of flour trade in the city. La Fuente was forced to flee across the rooftops and finally found shelter on a foreign ship anchored in Callao. The president of the Senate, Andrés Reyes y Buitrón, was then in charge of supreme command until December 21, 1831, when Gamarra returned. From September 27 to November 1, 1832, Gamarra, suffering from illness, entrusted command to the then president of the Senate, Manuel Tellería Vicuña. On July 30, 1833, Gamarra, before leaving to suppress a rebellion in Ayacucho, entrusted command to the vice president of the Senate José Braulio del Camporredondo. He regained power on November 2 of the same year.

Important works and events[edit]

Peace with Colombia[edit]

As soon as the coup d'état against La Mar occurred, Gamarra signed the Armistice of Piura on July 10, 1829, by which a 60-day armistice was agreed (which was extended at the end of said period), in addition to the return of Guayaquil to Gran Colombia and the suspension of the Peruvian blockade of the southern coast of Gran Colombia. Subsequently, the Peruvian and Colombian delegates, José de Larrea y Loredo and Pedro Gual Escandón, met in Guayaquil, who signed a treaty of peace and friendship on September 22, 1829, the so-called Treaty of Guayaquil. Thus, hostilities were officially put to an end, establishing "a perpetual and inviolable peace, and constant and perfect friendship between both nations." The dissolution of the Grand Colombian state led to the expiration of the treaty and the territorial dispute remained unsolved.

First treaty with Ecuador[edit]

In 1830, the Republic of Ecuador emerged as an independent state, seceding from Colombia. The brand new republic was built on the basis of the territories of the Real Audiencia of Quito, plus Guayaquil. At that time it did not make claims on [Tumbes Province|Tumbes]], Jaén and Maynas. The first treaty concluded between both states was the Pando–Noboa Treaty, signed on July 12, 1832 by the Minister of Government and Foreign Affairs of Peru, José María Pando, and the Plenipotentiary Minister of Ecuador, Diego Noboa. Its article 14 recognised and respected the current limits between both nations.

Treaties with Bolivia[edit]

In 1831 Gamarra wanted to declare war on Bolivia but Congress opposed it. Then he decided to start negotiations with that country. The representatives of both countries, the Peruvian Pedro Antonio de La Torre and the Bolivian Miguel María de Aguirre, met in Tiquina, signing a preliminary peace treaty on August 25, 1831, in which it was agreed the withdrawal of both armies from the border and the reduction of their troops. On November 8, 1831, the same plenipotentiaries, with the mediation of Chile, signed the Treaty of Peace and Friendship in Arequipa, which ratified the previous agreements, in addition to the prohibition of seditious activities for political refugees from both countries, and the maintenance of borders until the appointment of boundary commissions. At the same time, the Trade Treaty was celebrated, in which equal rights were approved, navigation on Lake Titicaca was declared free, and some items necessary for the industry and agriculture of both countries were exempt. The Bolivian government accepted the Treaty of Peace and Friendship, but not the Trade Treaty, considering it harmful to its commercial interests. The Peruvian La Torre was forced to travel to Bolivia to negotiate with the Bolivian representative Casimiro Olañeta a new Trade Treaty, which was signed in Chuquisaca on November 17, 1832.

Administrative policy[edit]