TMED5

| TMED5 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Identifiers | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Aliases | TMED5, CGI-100, p28, p24g2, transmembrane p24 trafficking protein 5 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| External IDs | OMIM: 616876 MGI: 1921586 HomoloGene: 4996 GeneCards: TMED5 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Wikidata | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Transmembrane emp24 domain-containing protein 5 is a protein that in humans is encoded by the TMED5 gene.[5]

Gene[edit]

General properties[edit]

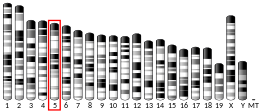

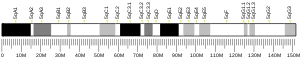

TMED5 (transmembrane emp24 domain-containing protein 5) is also known as p28, p24g2, and CGI-100.[5] The human gene spans 30,775 base pairs over 4 exons and 3 introns for transcript variant 1, 5 exons and 4 introns for transcript variant 2, and it is located on the minus strand of chromosome 1, at 1p22.1.[6]

Expression[edit]

TMED5 has ubiquitous expression with transcripts detected in 246 tissues.[7] Androgen deprivation led to lower expression in mice splenocytes compared to the control.[8] Human dendritic cells infected with Chlamydia pneumoniae showed an absence of TMED5 expression compared to uninfected dendritic cells which had moderate expression.[9]

mRNA transcript[edit]

TMED5 has two coding transcript variants and one non-coding transcript variant produced by alternative splicing.[7] Isoform 1 has 4 exons and encodes a protein 229 amino acids. Isoform 2 has 5 exons and encodes a protein with a shorter C-terminus 193 amino acids due to an additional exon causing a frameshift.[5]

Protein[edit]

General properties[edit]

TMED5 contains a signal peptide.[10] After cleavage of the signal peptide, TMED5 isoform 1 is composed of 202 amino acids and has a molecular weight of ~23 kDa.[11] The mature form of isoform 2 is composed of 166 amino acids and has a molecular weight of ~19 kDa.[12] Both isoforms have an isolectric point of approximately 4.6.[13]

Composition[edit]

Compared to the reference set of human proteins, TMED5 has fewer alanine and proline residues but more aspartic acid and phenylalanine residues.[14] TMED5 isoform 1 has one hydrophobic segment that corresponds with its transmembrane region.[14]

Domains and motifs[edit]

TMED5 isoform 1 is a single-pass transmembrane protein and is composed of a lumenal domain, one transmembrane (helical) domain, and a cytoplasmic domain.[7]

TMED5 is part of the emp24/gp25L/p24 family/GOLD family protein.[7]

TMED5 contains a di-lysine motif and predicted NLS in its cytoplasmic tail.[16][17]

Structure[edit]

The structure of TMED5 isoform 1 consists of beta strands making up the lumenal region, disparate coil-coiled regions, alpha helices making up the transmembrane domain, and alpha helices making up some of the cytoplasmic domain.[18][19]

Post-translational modifications[edit]

TMED5 has two predicted phosphorylation sites in the cytosolic region, Ser227 and Thr229.[21][22]

Localization[edit]

TMED5's predicted location is in the plasma membrane, with an extracellular N-terminus and intracellular C-terminus. TMED5's localization is predicted to be cytoplasmic, but has been found in some tissues to be located in the nucleus.[17][23]

Interacting proteins[edit]

The following table provides a list of proteins most likely to interact with TMED5. Not shown in the table are Wnt family proteins which are known to interact with the p24 protein family.[24]

| Protein Name | Protein Abrev | DB Source | Species | Evidence | Interaction | PubMed ID |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Transmembrane emp24 domain-containing protein 2 | TMED2 | IntAct | Homo sapiens | Anti tag coimmunoprecipitation[25] | Association | 28514442 |

| Transmembrane emp24 domain-containing protein 10 | TMED10 | IntAct | Mus musculus | Anti tag coimmunoprecipitation[26] | Association | 26496610 |

| Protein ERGIC-53 | LMAN1 | MINT | Homo sapiens | Fluorescence microscopy[27] | Colocalization | 22094269 |

| C-X-C motif chemokine 9 | CXCL9 | IntAct | Homo sapiens | Validated two hybrid[28] | Physical Association | 32296183 |

| Protein arginine N-methyltransferase 6 | PRMT6 | MINT | Homo sapiens | Two hybrid[29] | Physical Association | 23455924 |

| Phosphatidylethanolamine-binding protein 1 | PEBP1 | IntAct | Homo sapiens | Anti tag coimmunoprecipitation[30] | Association | 31980649 |

| Kinase suppressor of Ras 1 | KSR1 | IntAct | Homo sapiens | Anti tag coimmunoprecipitation[31] | Association | 27086506 |

| Endothelial lipase | LIPG | IntAct | Mus musculus | Anti tag coimmunoprecipitation[32] | Association | 28514442 |

| Histone-lysine N-methyltransferase PRDM16 | Prdm16 | MINT | Mus musculus | Anti tag coimmunoprecipitation[33] | Association | 30462309 |

| Intracellular growth locus, subunit C | iglC2 | MINT | Francisella tularensis | Two hybrid pooling approach[34] | Physical Association | 26714771 |

| ORF9C | ORF9C | BioGRID | SARS-Cov-2 | Affinity Capture-MS[35] | Association | 32353859 |

| Uncharacterized protein 14 | ORF14 | IntAct | SARS-Cov-2 | Pull down[35] | Association | 32353859 |

Function and clinical significance[edit]

TMED5 is a part of the p24 protein family whose general functions are protein trafficking for the secretory pathway.[36] TMED5 is thought to be necessary in the formation of the Golgi into a ribbon.[37]

Glycosylphosphatidylinositol-anchored proteins (GPI-AP) depend on p24 cargo receptors for transport from the ER to the Golgi.[38] Knockdown of p24γ2 (a mouse ortholog of TMED5) in mice resulted in impaired transport of GPI-AP. The study concluded that the α-helical region of p24γ2 binds GPI which is necessary to incorporate it into COPII transport vesicles.[38]

TMED5 is reported to be necessary for the secretion of Wnt ligands. TMED5 has been found to interact with WNT7B, activating the canonical WNT-CTNNB1/β-catenin signaling pathway.[39] This pathway is linked to numerous cancers because upregulation of the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway leads to cytosolic accumulation of β-catenin, promoting cellular proliferation.[40]

Research has identified bladder cancer to have a common chromosomal amplification at 1p21-22 and showed significant upregulation of TMED5.[41]

Evolution[edit]

Homology[edit]

Paralogs[edit]

TMED5 paralogs include TMED1, TMED2, TMED3, TMED4, TMED6, TMED7, TMED8, TMED9, and TMED10.[42] All paralogs share the conserved transmembrane domain and contain the characteristic GOLD domain as included in the emp24/gp25L/p24 family/GOLD family proteins.[7]

Orthologs[edit]

TMED5 is found to be conserved in vertebrates, invertebrates, plants and fungi, and there are 243 known organisms that have orthologs with the gene.[5] The following table provides a sample of the ortholog space of TMED5.

| Genus and Species | NCBI Accession Number | Date of Divergence (MYA)[43] | Sequence Length | Sequence Identity[42] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Homo sapiens (Human) | NP_057124.3 | 0 | 229 | 100 |

| Pan troglodytes (Chimpanzee) | XP_001154650.1 | 6 | 229 | 99.6 |

| Mus musculus (Mouse) | NP_083152.1 | 89 | 229 | 90 |

| Monodelphis domestica (Gray short-tailed opossum) | XP_016284519.1 | 160 | 228 | 84 |

| Gallus gallus (Chicken) | NP_001007957.1 | 318 | 226 | 83 |

| Gekko japonicus (Gekko) | XP_015268825.1 | 318 | 245 | 73.1 |

| Xenopus tropicalis (Western clawed frog) | XP_031755940.1 | 351 | 223 | 67.7 |

| Danio rerio (Zebrafish) | NP_956697.1 | 433 | 225 | 65.1 |

| Rhincodon typus (Whale shark) | XP_020385910.1 | 465 | 224 | 66.8 |

| Octopus vulgaris (Octopus) | XP_029646555.1 | 736 | 239 | 42.5 |

| Cryptotermes secundus (Termite) | XP_023712535.1 | 736 | 235 | 37.5 |

| Caenorhabditis elegans (Roundworm) | NP_502288.1 | 736 | 234 | 37.3 |

| Drosophila mojavensis (Fruit fly) | XP_002009472.2 | 736 | 239 | 36.3 |

| Eufriesea mexicana (Orchid bee) | XP_017762298.1 | 736 | 227 | 26.8 |

| Trichoplax adhaerens | XP_002108774.1 | 747 | 193 | 32.1 |

| Rhizopus microsporus | XP_023464765.1 | 1017 | 199 | 30.2 |

| Coprinopsis cinerea (Gray shag mushroom) | XP_001836898.2 | 1017 | 199 | 28.5 |

| Kluyveromyces lactis | XP_453709.1 | 1017 | 208 | 28.1 |

| Rhodamnia argentea (Malletwood) | XP_030545696.1 | 1275 | 217 | 28.9 |

| Quercus suber (Cork oak) | XP_023882547.1 | 1275 | 277 | 28.7 |

| Vitis riparia (Riverbank grape) | XP_034686416.1 | 1275 | 215 | 27.3 |

References[edit]

- ^ a b c GRCh38: Ensembl release 89: ENSG00000117500 – Ensembl, May 2017

- ^ a b c GRCm38: Ensembl release 89: ENSMUSG00000063406 – Ensembl, May 2017

- ^ "Human PubMed Reference:". National Center for Biotechnology Information, U.S. National Library of Medicine.

- ^ "Mouse PubMed Reference:". National Center for Biotechnology Information, U.S. National Library of Medicine.

- ^ a b c d National Center for Biotechnology Information. "Transmembrane p24 trafficking protein 5". NCBI Gene.

- ^ Weizmann Institute of Science. "TMED5 Gene". Gene Cards Human Gene Database.

- ^ a b c d e UniProt Consortium. "TMED5 gene". UniProtKB.

- ^ National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI). "GDS5301 Expression Profile". Gene Expression Omnibus Repository.

- ^ National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI). "GDS3573 Expression Profile". Gene Expression Omnibus Repository.

- ^ Center of Biological Sequential Analysis. "SignalP-5.0 Server". Prediction Servers.

- ^ National Center for Biotechnology Information. "Transmembrane emp24 domain-containing protein 5 isoform 1 precursor". NCBI Protein.

- ^ National Center for Biotechnology Information. "Transmembrane emp24 domain-containing protein 5 isoform 2 precursor". NCBI Protein.

- ^ Swiss Institute of Bioinformatics. "Compute pI/Mw Tool". ExPASy.

- ^ a b European Molecular Biology Laboratory - European Bioinformatics Institute (EMBL-EBI). "Statistical Analysis of Protein Sequences (SAPS)".

- ^ a b Protter: interactive protein feature visualization and integration with experimental proteomic data. Omasits U, Ahrens CH, Müller S, Wollscheid B. Bioinformatics. 2014 Mar 15;30(6):884-6. doi:10.1093/bioinformatics/btt607

- ^ The Eukaryotic Liner Motif (ELM) resource for Functional Sites in Proteins. "ELM prediction".

- ^ a b Prediction of Protein Sorting Signals and Localization Sites in Amino Acid Sequences. "PSORT II Prediction". PSORT WWW Server.

- ^ Max Planck Institute (MPI) for Developmental Biology, Tübingen, Germany. "Ali2D". MPI Bioinformatics Toolkit.

- ^ University of Michigan. "I-TASSER Protein Structure & Function Predictions". Zhang Lab.

- ^ Kelley, L., Mezulis, S., Yates, C. et al. The Phyre2 web portal for protein modeling, prediction and analysis. Nat Protoc 10, 845–858 (2015). doi:10.1038/nprot.2015.053

- ^ Swiss Institute of Bioinformatics. "MyHits Motif Scan". ExPASy.

- ^ Blom, Nikolaj. "Net Phos 3.1 Server". DTU Bioinformatics.

- ^ Tissue Atlas. "Tissue expression of TMED5". The Human Protein Atlas.

- ^ Buechling, T., Chaudhary, V., Spirohn, K., Weiss, M. and Boutros, M. (2011), p24 proteins are required for secretion of Wnt ligands. EMBO reports, 12: 1265-1272. doi:10.1038/embor.2011.212

- ^ Huttlin, E. L., Bruckner, R. J., Paulo, J. A., Cannon, J. R., Ting, L., Baltier, K., Colby, G., Gebreab, F., Gygi, M. P., Parzen, H., Szpyt, J., Tam, S., Zarraga, G., Pontano-Vaites, L., Swarup, S., White, A. E., Schweppe, D. K., Rad, R., Erickson, B. K., Obar, R. A., … Harper, J. W. (2017). Architecture of the human interactome defines protein communities and disease networks. Nature, 545(7655), 505–509. doi:10.1038/nature22366

- ^ Hein, M. Y., Hubner, N. C., Poser, I., Cox, J., Nagaraj, N., Toyoda, Y., Gak, I. A., Weisswange, I., Mansfeld, J., Buchholz, F., Hyman, A. A., & Mann, M. (2015). A human interactome in three quantitative dimensions organized by stoichiometries and abundances. Cell, 163(3), 712–723. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2015.09.053

- ^ Buechling, T., Chaudhary, V., Spirohn, K., Weiss, M., & Boutros, M. (2011). p24 proteins are required for secretion of Wnt ligands. EMBO reports, 12(12), 1265–1272. doi:10.1038/embor.2011.212

- ^ Luck, K., Kim, D. K., Lambourne, L., Spirohn, K., Begg, B. E., Bian, W., Brignall, R., Cafarelli, T., Campos-Laborie, F. J., Charloteaux, B., Choi, D., Coté, A. G., Daley, M., Deimling, S., Desbuleux, A., Dricot, A., Gebbia, M., Hardy, M. F., Kishore, N., Knapp, J. J., … Calderwood, M. A. (2020). A reference map of the human binary protein interactome. Nature, 580(7803), 402–408. doi:10.1038/s41586-020-2188-x

- ^ Weimann, M., Grossmann, A., Woodsmith, J., Özkan, Z., Birth, P., Meierhofer, D., Benlasfer, N., Valovka, T., Timmermann, B., Wanker, E. E., Sauer, S., & Stelzl, U. (2013). A Y2H-seq approach defines the human protein methyltransferase interactome. Nature methods, 10(4), 339–342. doi:10.1038/nmeth.2397

- ^ Kennedy, S. A., Jarboui, M. A., Srihari, S., Raso, C., Bryan, K., Dernayka, L., Charitou, T., Bernal-Llinares, M., Herrera-Montavez, C., Krstic, A., Matallanas, D., Kotlyar, M., Jurisica, I., Curak, J., Wong, V., Stagljar, I., LeBihan, T., Imrie, L., Pillai, P., Lynn, M. A., … Kolch, W. (2020). Extensive rewiring of the EGFR network in colorectal cancer cells expressing transforming levels of KRASG13D. Nature communications, 11(1), 499. doi:10.1038/s41467-019-14224-9

- ^ Bryan, K., Jarboui, M. A., Raso, C., Bernal-Llinares, M., McCann, B., Rauch, J., Boldt, K., & Lynn, D. J. (2016). HiQuant: Rapid Postquantification Analysis of Large-Scale MS-Generated Proteomics Data. Journal of proteome research, 15(6), 2072–2079. doi:10.1021/acs.jproteome.5b01008

- ^ Huttlin, E. L., Bruckner, R. J., Paulo, J. A., Cannon, J. R., Ting, L., Baltier, K., Colby, G., Gebreab, F., Gygi, M. P., Parzen, H., Szpyt, J., Tam, S., Zarraga, G., Pontano-Vaites, L., Swarup, S., White, A. E., Schweppe, D. K., Rad, R., Erickson, B. K., Obar, R. A., … Harper, J. W. (2017). Architecture of the human interactome defines protein communities and disease networks. Nature, 545(7655), 505–509. doi:10.1038/nature22366

- ^ Ivanochko, D., Halabelian, L., Henderson, E., Savitsky, P., Jain, H., Marcon, E., Duan, S., Hutchinson, A., Seitova, A., Barsyte-Lovejoy, D., Filippakopoulos, P., Greenblatt, J., Lima-Fernandes, E., & Arrowsmith, C. H. (2019). Direct interaction between the PRDM3 and PRDM16 tumor suppressors and the NuRD chromatin remodeling complex. Nucleic acids research, 47(3), 1225–1238. doi:10.1093/nar/gky1192

- ^ Wallqvist, A., Memišević, V., Zavaljevski, N., Pieper, R., Rajagopala, S. V., Kwon, K., Yu, C., Hoover, T. A., & Reifman, J. (2015). Using host-pathogen protein interactions to identify and characterize Francisella tularensis virulence factors. BMC genomics, 16, 1106. doi:10.1186/s12864-015-2351-1

- ^ a b Gordon, D. E., Jang, G. M., Bouhaddou, M., Xu, J., Obernier, K., White, K. M., O'Meara, M. J., Rezelj, V. V., Guo, J. Z., Swaney, D. L., Tummino, T. A., Hüttenhain, R., Kaake, R. M., Richards, A. L., Tutuncuoglu, B., Foussard, H., Batra, J., Haas, K., Modak, M., Kim, M., … Krogan, N. J. (2020). A SARS-CoV-2 protein interaction map reveals targets for drug repurposing. Nature, 583(7816), 459–468. doi:10.1038/s41586-020-2286-9

- ^ Pastor-Cantizano, N., Montesinos, J.C., Bernat-Silvestre, C. et al. p24 family proteins: key players in the regulation of trafficking along the secretory pathway. Protoplasma 253, 967–985 (2016).doi:10.1007/s00709-015-0858-6

- ^ Koegler, E., Bonnon, C., Waldmeier, L., Mitrovic, S., Halbeisen, R. and Hauri, H.‐P. (2010), p28, A Novel ERGIC/cis Golgi Protein, Required for Golgi Ribbon Formation. Traffic, 11: 70-89. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0854.2009.01009.x

- ^ a b Theiler, R., Fujita, M., Nagae, M., Yamaguchi, Y., Maeda, Y., & Kinoshita, T. (2014). The α-helical region in p24γ2 subunit of p24 protein cargo receptor is pivotal for the recognition and transport of glycosylphosphatidylinositol-anchored proteins. The Journal of biological chemistry, 289(24), 16835–16843. doi:10.1074/jbc.M114.568311

- ^ Zhen Yang, Qi Sun, Junfei Guo, Shixing Wang, Ge Song, Weiying Liu, Min Liu & Hua Tang (2019) GRSF1-mediated MIR-G-1 promotes malignant behavior and nuclear autophagy by directly upregulating TMED5 and LMNB1 in cervical cancer cells, Autophagy, 15:4, 668-685, doi:10.1080/15548627.2018.1539590

- ^ Pai, S.G., Carneiro, B.A., Mota, J.M. et al. Wnt/beta-catenin pathway: modulating anticancer immune response. J Hematol Oncol 10, 101 (2017). doi:10.1186/s13045-017-0471-6

- ^ Scaravilli, M., Asero, P., Tammela, T.L. et al. Mapping of the chromosomal amplification 1p21-22 in bladder cancer. BMC Res Notes 7, 547 (2014). doi:10.1186/1756-0500-7-547

- ^ a b National Center for Biotechnology Information. "Standard Protein BLAST".

- ^ Temple University Center of Biodiversity. "Pairwise Divergence Time". Timetree: The Timescale of Life.