Blackfriars, Leicester

Seal of St Clement’s Priory and map of the Leicester Blackfriars site | |

| Monastery information | |

|---|---|

| Other names | St Clement’s Priory, Leicester, Leicester Dominicans, ’Le Blak Frears in le Ashes’ |

| Order | Dominican Order |

| Established | 13th Cent (Probably 1247-1254) |

| Disestablished | 10th Nov. 1538 |

| Dedicated to | St Clement |

| Diocese | Lincoln |

| People | |

| Founder(s) | Simon de Montfort |

| Site | |

| Coordinates | 52°38′13″N 1°08′40″W / 52.63695°N 1.144386°W |

| Visible remains | None |

Blackfriars Leicester, also known as St Clement’s Church, Leicester and St Clement’s Priory, Leicester, is a former priory of the Order of Preachers (also called Dominican Friars or Black Friars) in Leicester, England. It is also the name of a former civic parish, and a neighbourhood in the city built on and around the site of the old priory.

Roman History[edit]

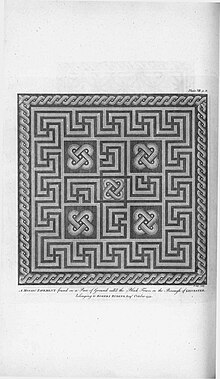

The St Clement’s church, and later the Dominican priory, would come to be established inside the far north west corner of the (now vanished) city walls of Ratae Corieltauvorum - the Roman town at the core of modern Leicester. The site is a few hundred meters north of the surviving Roman Jewry Wall, the old bathhouse. From the discovery of the three Blackfriars Pavements, some of the finest Roman mosaics to survive in Britain (see gallery below), it is clear there was a very wealthy Roman townhouse constructed on what would become the priory site, the Blackfriars Villa.[1]

St Clement’s Church[edit]

The Parish Church of St. Clement’s (along with St Nicholas, St Peter’s, St Mary de Castro, St Michael’s, St Margaret’s, and St Martin’s) was one of the seven ancient parish churches of the Medieval Borough of Leicester.[2] In the mid 13th century it’s advowson was passed to the Order of Preaches (Blackfriars), who constructed convent buildings adjacent to it, and it became a priory church.[3] Like St Peter’s, and St Michael’s, there are no longer any visible remains of it above ground.

In 2018 the structure of what is likely to have been the church of St Clement’s was discovered on what is now All Saints Road. Many of the burials on the site can be dated between 1000 and 1100 - implying a burial site and possibly a church from at least the 11th century.[4][5][6]

Parish Church before Dominican Incardination[edit]

Dedicated to St Clement of Rome[7] (an early Pope and Martyr) and with unknown 11th cent origins it stood in the northwest part of the old Roman city, probably on what is now All Saints Road. In 1107 it’s advowson was granted to the canons of St Mary de Castro by Robert de Beaumont, 1st Earl of Leicester, along with those of all the other parish churches in the town (apart from St Margaret’s). Upon the foundation of Leicester Abbey in 1143 by Robert de Beaumont, 2nd Earl of Leicester, it took possession of the canonical college at St Mary’s along with its possessions including St Clement’s.[8] Before their expulsion in 1250, the southern part of the parish as well as parts of the neighbouring parish of St Nicholas, was home to the towns Jewish community - an area known as Leicester’s Jewry, hence the name of the Jewry Wall.[9]

A large burial ground dating to 11th cent was discovered parallel to what are likely the archeological remains of the church in 2018. There were 456 unearthed burials with 254 in mass graves. The mass graves date to the 11th century at least three quarters of a century to a century and a half before the 1173 siege and nearly two centuries before the Black Death. Clearly buried with Christian honour and in a position parallel to the church, it has been suggested that the 254 are victims of a famine in 1087 reported by the Anglo Saxon Chronicle. Unusually 96 pairs of skeletons were found in double graves suggesting the site was used for the burial of married couples.[10][11][12]

In 1173 Robert Blanchemains, 3rd Earl of Leicester became a principal rebel in the Revolt of 1173–1174 leading to the destruction of many homes in the parish during the Siege of Leicester that year.[13] St Clement’s was probably the worst effected parish in the city and the church likely suffered damage.[14]

The last records we have of the parish as under the oversight of Leicester abbey are from the 1220s. Perhaps due to the large undeveloped areas of the parish and those given over to burials, perhaps because of the number of Jews resident in the south of the parish (Leicesters Old Jewry), and perhaps due to the Siege of 1173 by 1220 the parish could scarcely afford a priest. In 1221-2 we have a record of the vicarage with a stipend of 20 Shillings per annum and a corody granted by the Abbey. This implies the parish was becoming a financial burden on the abbey rather than the asset parish advowsons were intended to be.[15][16]

St Clement’s after the Dominican Incardination[edit]

The relationship the Dominican priory had with the parish and church of St Clement is contested (see Discussion). Leicester Abbey only had the right to grant the advowson; i.e. the rights to the chancel and any incomes intend to support the clergy of the church while the parishioners retained control of the nave with any parish dissolution requiring a complex legal process of which there is no record. It is possible that the nave remained a Parish Church with its own priest (probably a friar of the priory).[17] It is also possible the records of the parish dissolution are simply missing and that the building was handed over in its entirety to be a Priory Church (see Discussion on Location 2.1, & 2.2). In either case, the church would have become noted for its choral office, with a much larger choir than the parish church’s, and the townsfolk able to hear and watch the conventual mass and other services through the rood screen. Another peculiarity would have been it’s liturgy. Leicesters other churches all used the Diocese of Lincoln’s variation on the Sarum Ritual whereas at St Clement’s the masses would have been celebrated according to the Dominican Ritual. The church would have also observed a slightly different calendar of saints.[18]

Whatever happened to the geographical parish in the 13th cent it is well documented that either the site of the priory or it’s site including the tiny ancient parish did not fall under any parochial jurisdiction of the Church of England until the late 19th cent, the 1538 parish boundaries never being redrawn.[19]

By the time of the reformation there were numerous burials and fine funerary ornaments in St Clement’s, aside from the burial’s discovered in 2018. In 1331 one Philip Danet sought to establish a chantry for his soul in the church, to be served by a chantry priest of the college of St Leonard’s[20][21] and there were likely a number of chantry chapels. In 1536 before the priory was dissolved and the church demolished John Leland, the antiquary, recorded this after visiting:

“I saw in the quire of the Blake-Freres the tumbes of… [manuscript text missing or illegible]… and a flat alabaster stone [with] the name of Lady Isabel, w[ife] to Sr. John Beauchaump of Ho[lt.] And in the north isle I saw the tumbe of another knight without scripture. And in the north crosse isle [a tombe] having the name of Roger Po[inter] of Leircester armid. These thinges brevely (i.e. briefly) I markid at Leyrcester.”[22]

John Lelands few lines constitute the only surviving witness testimony of the building. The Church was demolished not many years after the dissolution and many years prior to the rest of the conventual buildings.

St Clement’s Priory (Blackfriars)[edit]

Background[edit]

The 13th century was a period of rapid and significant reform for both religious life and the wider church in Europe, marked by the establishment of many new communities. Notable among these were the new travelling mendicant monks known as friars. In Leicester this wider reform was felt by the arrival of the mendicant orders between the 1220s and the 1250s and the establishment of three new religious houses in the city: the Order of Friars Minor (Greyfriars) at the Friary of St. Mary Magdalene, before 1230; the Order of Hermits of St. Augustine (Friars Hermits or Austin Friars) at St. Katherine’s Priory, in the year 1254; and at some point in the mid 13th cent (see below and Discussion) the Order of Preachers (Blackfriars) at the parish church of St. Clement.[24] These orders sought to bring the monastic example and a more professional spiritual ministry to the town, partly by observing the Liturgy of the Hours and monastic community life in accessible reach of townsfolk, and also by providing professional religious ministry and education, as well as medical and pastoral care to the growing urban population.[25][26]

The Blackfriars (also called Friars Preachers) were and continue to be focussed on prayer and liturgy, academic scholarship (primarily but far from exclusively philosophical, theological, and biblical), teaching and education, scholarly and rhetorical excellence in public preaching, and pastoral and charity work in urban areas. Of all the new orders they were most focused on promoting the normative teachings of the Catholic Church and came to have a significant role in inquisition and combating heresy throughout catholic Europe.[27] Two Dominican mottos, Contemplata aliis tradere, or, “To contemplate and to pass the fruits of contemplation to others”, together with the one shown on the Dominican seal (see image) succinctly express their mission.[28]

The Dominican connection with the Earls of Leicester predates the foundation in Leicester and even the establishment of the Dominican Order itself. St Dominic and his early companions mission to preach against the Cathar heresy bought him into contact with Simon, 5th Earl as early as 1209 who was involved in a military campaign against the Cathars (part of a series of campaigns known as the Albigensian Crusades) parallel to Dominics preaching campaign. The 5th Earl believed very strongly in the power of Dominic’s prayers in his military battles and had his daughter baptised by the saint. It is likely the Earls young son, the famous Simon de Montfort also met Dominic while accompanying his father on these campaigns.[29]

Foundation, Site, & Governance[edit]

It is very difficult to date precisely both the arrival of the first friars to Leicester and the subsequent establishment of their priory at St Clement’s (see discussion). The order came to England in 1221 (not the date Nichols notes of 1217). Sources suggest they arrived in Leicester either before 1233[30] or in 1247.[31] The establishment of the house has been dated to before 1252,[32] but this has been disputed[33] and the founding charter does not survive. However it is almost beyond doubt that Simon de Montfort established the house given its founding grant involved lands from the castle, lands that only Simon could give.[34] Their incardination at Saint Clement’s (the advowson being granted by Leicester Abbey) likewise implies the involvement of the Earl who by his position was a principal patron of the Abbey.

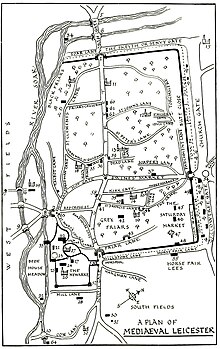

A site in the largely abandoned St Clements parish was provided including the parish church (as discussed above), its church yard to the north and a site to the south for the cloister and other convent buildings. After a number of adjacent properties were added to it over the years it came to 16 acres.[35] This now sits between Soar Lane to the north (running along the old north wall of the Roman city), Great Central Street (previously called Friars Preachers Lane) to the east, Holy Bones to the south, and the river Soar to the west and north. Jarvis Street runs through grounds of the priory and probably over part of the old cloister where it meets Alexander Street. The southern part of All Saints Road runs through the priory gardens. The odd numbered houses (35-53) on the northern part of All Saints Road and parts of Kilby Lane stand on the site of the churchyard and the mass graves while Grand Union Embankment is the site of the old Roman defences. The church sits partly under what is now the northern stretch of All Saints Road. The presence of the priory is remembered in the name of Blackfriars Street and Friars Causeway (which possibly marked the southern boarder of the site before its western section was demolished for the construction of the Great Central Railway).[36]

Like all Dominican communities it’s members followed the Rule of St Augustine, and were governed by the Prior elected by the community, the community chapter, and the wider Province.[37] Leicester was under the visitation of Oxford Blackfriars Priory.

History[edit]

Queen Eleanor, wife of King Henry III, left £5 in her will to the priory. In 1301 the priory received another royal gifts: seven oak trees (presumably the wood from which) from Rockingham Forest. Further monetary gifts from the royal family reveal that in 1328/29 there were 30 friars, and in 1334/35 there were 32.[33]

Leicester hosted the provincial chapters of the English Dominican Province in 1301, 1317 and 1334.[33]

In 1489 King Henry VII donated oaks to the priory for the reconstruction of the friar's dormitory.[33]

Dissolution[edit]

The priory was dissolved as part of King Henry VIII's dissolution of the monasteries and was surrendered in November 1538.[38] At the time the house was home to the prior and nine friars.[33] The former priory was granted to Henry Grey, 1st Duke of Suffolk, in 1546.[39]

There are no visible remains of the priory.[38]

Nineteenth Century Reestablishment[edit]

The Friars Preachers returned to Leicester in 1819 after over 280 years in exile. In 1882 they established a new foundation, The Priory of the Holy Cross, on New Walk to the south of the old city walls.[40] They are still active in the city as of 2024 with no plan to leave.[41]

Priors of St Clement’s Priory, Leicester[edit]

List of known priors of Leicester Blackfriars:

- John Garland O.P. occurs 1394

- William Ceyton O.P. occurs 1505 (variously recorded as Clayton, Layton, or Ceyton)

- Ralph Burrell O.P. occurs 1538

Civil parish[edit]

Leicester Blackfriars was a civil parish, in 1891 the parish had a population of 2512.[42] The parish was formed in 1858,[43] on 26 March 1896 the parish was abolished and merged with Leicester.[44]

Gallery[edit]

Roman Remains at Blackfriars[edit]

Blackfriars Site Today[edit]

Post Reformation Dominican Presence in Leicester[edit]

Sources[edit]

- Charles J. Billson, ‘Medieval Leicester’ (1920): Chapter One, part of Section 1 and all of section 4, ‘On the North Quarter’ & ‘On the West Quarter’ (see here).

- Charles J. Billson, ‘Medieval Leicester’ (1920): Chapter 6, Section 1, ‘On the Church of St. Clements’ (see here)

- John Nichols. ‘History & Antiquities of Leicestershire’ (1815), Volume I.II, ‘On the Dominicans or Blackfriars’. Page 295-6 (see here).

- The Rev. C.F.R. Palmer. O.P. ‘Paper on the Blackfriars of Leicester presented to The Leicester Architectural & Archeological Society, May 28th, 1883’ (see here).

- Victoria County History, ‘A History of the County of Leicestershire’ (1954), Volume II, ‘On Friaries’, ‘Friaries in Leicester’ (see see here).

- Victoria County History, ‘A History of the County of Leicestershire’ (1958), Volume IV, ‘On the Ancient Borough’, ‘Lost Churches’ (see see here).

References[edit]

- ^ M.Morris, G.Savani, & S.Scott|Life in Roman Leicester|2018|University of Leicester ISBN 978-0-9574792-5-8

- ^ "The ancient borough: Lost churches | British History Online". www.british-history.ac.uk. Retrieved 4 April 2024.

- ^ "Mediaeval Leicester/Chapter 6 - Wikisource, the free online library". en.wikisource.org. Retrieved 4 April 2024.

- ^ ULASNews (30 November 2018). "November: medieval cemetery at Waterside, Leicester". ULAS News. Retrieved 4 April 2024.

- ^ ULASNews (14 January 2019). "Roman and medieval discoveries: Waterside, Leicester". ULAS News. Retrieved 4 April 2024.

- ^ ULASNews (7 April 2020). "Life and Death on the Waterside". ULAS News. Retrieved 4 April 2024.

- ^ "Mediaeval Leicester/Chapter 6 - Wikisource, the free online library". en.wikisource.org. Retrieved 4 April 2024.

- ^ "The ancient borough: Lost churches | British History Online". www.british-history.ac.uk. Retrieved 4 April 2024.

- ^ "Mediaeval Leicester/Chapter 1 - Wikisource, the free online library". en.wikisource.org. Retrieved 4 April 2024.

- ^ ULASNews (30 November 2018). "November: medieval cemetery at Waterside, Leicester". ULAS News. Retrieved 4 April 2024.

- ^ ULASNews (14 January 2019). "Roman and medieval discoveries: Waterside, Leicester". ULAS News. Retrieved 4 April 2024.

- ^ ULASNews (7 April 2020). "Life and Death on the Waterside". ULAS News. Retrieved 4 April 2024.

- ^ "The Castle Motte - Story of Leicester". www.storyofleicester.info. Retrieved 4 April 2024.

- ^ "Mediaeval Leicester/Chapter 6 - Wikisource, the free online library". en.wikisource.org. Retrieved 4 April 2024.

- ^ "The ancient borough: Lost churches | British History Online". www.british-history.ac.uk. Retrieved 4 April 2024.

- ^ "Mediaeval Leicester/Chapter 6 - Wikisource, the free online library". en.wikisource.org. Retrieved 4 April 2024.

- ^ "Mediaeval Leicester/Chapter 6 - Wikisource, the free online library". en.wikisource.org. Retrieved 4 April 2024.

- ^ Hinnebusch, William A. (1975). The Dominicans: A Short History. Dominican Publications. ISBN 978-0-907271-61-1. Archived from the original on 8 May 2020. Retrieved 22 February 2015.

- ^ Transactions of the Leicestershire Architectural and Archaeological Society. The Society. 1888.

- ^ "Mediaeval Leicester/Chapter 6 - Wikisource, the free online library". en.wikisource.org. Retrieved 4 April 2024.

- ^ "The ancient borough: Lost churches | British History Online". www.british-history.ac.uk. Retrieved 4 April 2024.

- ^ LELAND, JOHN. ITINERARY IN ENGLAND. (1535-1543) PART I. ENTRY FOR LEICESTER 1536. Pages 14-15 | https://ia802703.us.archive.org/29/items/itineraryofjohnl01lelauoft/itineraryofjohnl01lelauoft.pdf

- ^ Nichols, John, History and Antiquities of the County of Leicester, 1795–1815, Vol I part II, plate XVII, fig. 11 (facing p.272), also page 299 where Nichols quotes Rev Francis Peck’s description of the image MSS Vol V ( Harl. MSS 4938)p.11.|https://specialcollections.le.ac.uk/digital/collection/p15407coll6/id/3465

- ^ "Dominicans or Black Friers". specialcollections.le.ac.uk. Retrieved 4 April 2024.

- ^ "Friar | Definition & Orders | Britannica". www.britannica.com. Retrieved 4 April 2024.

- ^ "Monasticism - Mendicant, Friars, Orders | Britannica". www.britannica.com. Retrieved 4 April 2024.

- ^ Hinnebusch, William A. (1975). The Dominicans: A Short History. Dominican Publications. ISBN 978-0-907271-61-1. Archived from the original on 8 May 2020. Retrieved 22 February 2015.

- ^ "Monasticism - Mendicant, Friars, Orders | Britannica". www.britannica.com. Retrieved 4 April 2024.

- ^ OP, Fr Gabriel Gillen (17 January 2015). "St. Dominic Meets Simon de Montfort". Dominican Friars Foundation. Retrieved 4 April 2024.

- ^ "The English Dominican Province (1221 - 1921)" (PDF). Retrieved 4 April 2024.

- ^ O.P, Br Christopher Pierce (30 October 2014). "Dominican Priories: Leicester". The Dominican Friars in Britain. Retrieved 4 April 2024.

- ^ Transactions of the Leicestershire Architectural and Archaeological Society. The Society. 1888.

- ^ a b c d e "Friaries: Friaries in Leicester | British History Online". www.british-history.ac.uk. Retrieved 4 April 2024.

- ^ Transactions of the Leicestershire Architectural and Archaeological Society. The Society. 1888.

- ^ "Dominicans or Black Friers". specialcollections.le.ac.uk. Retrieved 4 April 2024.

- ^ ULASNews (7 April 2020). "Life and Death on the Waterside". ULAS News. Retrieved 4 April 2024.

- ^ Hinnebusch, William A. (1975). The Dominicans: A Short History. Dominican Publications. ISBN 978-0-907271-61-1. Archived from the original on 8 May 2020. Retrieved 22 February 2015.

- ^ a b Historic England. "Leicester Blackfriars (867108)". Research records (formerly PastScape). Retrieved 26 June 2013.

- ^ "The ancient borough: Black Friars | British History Online". www.british-history.ac.uk. Retrieved 4 April 2024.

- ^ O.P, Br Christopher Pierce (30 October 2014). "Dominican Priories: Leicester". The Dominican Friars in Britain. Retrieved 4 April 2024.

- ^ "Holy Cross Leicester – News, events and information about Holy Cross Catholic Priory Church Leicester served by the Dominican Order". Retrieved 4 April 2024.

- ^ "Population statistics Leicester Blackfriars ExP/CP through time". A Vision of Britain through Time. Retrieved 4 January 2023.

- ^ "Relationships and changes Leicester Blackfriars ExP/CP through time". A Vision of Britain through Time. Retrieved 4 January 2023.

- ^ "Leicester Registration District". UKBMD. Retrieved 4 January 2023.