Article structure

Article structures in journalism encompass various formats to present information in news stories and feature articles. These structures reflect not only a writer's deliberate choice but also a response to editorial guidelines or the inherent demands of the story itself. While some writers may not consciously adhere to these structures, they often find them retrospectively aligned with their writing process. Conversely, others might consciously adopt a style as their story develops or adhere to predefined structures based on publisher guidelines.[1][2]

Common Article Structures[edit]

This section provides an in-depth look at various article structures used in journalism.

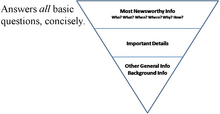

Inverted Pyramid[edit]

The inverted pyramid is a classic structure that begins with the most critical information, followed by supporting details, and concludes with background or supplementary data. It is predominantly used in news reporting and is sometimes critiqued for its direct approach.[3][4]

- Example 1: A news report on an earthquake would start with the magnitude and location, followed by details on damages and rescue efforts, and end with historical data on regional seismic activity.

- Example 2: In a political context, a news article about an election might begin with the election results, followed by an analysis of key races, and conclude with background information on the candidates.

Narrative[edit]

The narrative structure follows events in a chronological order, commonly utilized in feature writing and long-form journalism.[1]

- Example 1: A profile piece on a chef would start with their early life, follow their career development, and conclude with their current achievements.

- Example 2: In a historical feature article, the narrative structure could trace the timeline of a significant event, providing context and analysis along the way.

Hourglass[edit]

The hourglass combines the inverted pyramid and narrative styles, beginning with crucial details, transitioning into a narrative body, and ending with a summary.[4][1]

- Example 1: An article on new traffic regulations starts with the key decisions made, then narrates public reactions, and concludes with an overview of expected impacts.

- Example 2: In a scientific report, the hourglass structure may present research findings first, followed by the methodology used, and conclude with implications and future research directions.

Nut Graph[edit]

In the nut graph structure, a short paragraph provides the context and significance of the story, usually following the lead.[1]

- Example 1: A report on declining bee populations would start with this phenomenon, followed by a nut graph explaining its importance, and then delve into causes and effects.

- Example 2: In an economic analysis article, the nut graph could introduce a key economic trend, followed by a concise explanation of its implications for businesses and consumers.

Diamond[edit]

The diamond structure begins with an engaging anecdote, includes a nut graph, broadens with detailed information, and then converges back to the initial story. This format is favored in opinion journalism.[1][5]

- Example 1: An opinion piece about young entrepreneurs might start with a specific story, expand to discuss the broader trend, and then tie back to the initial anecdote.

- Example 2: In a cultural critique, the diamond structure could begin with a personal experience, delve into a broader analysis of cultural phenomena, and conclude by relating it to the initial experience.

Christmas Tree[edit]

The Christmas tree structure features a series of narrative developments or twists, often used for complex or evolving stories.[3]

- Example 1: A feature on a new technological breakthrough would present various aspects (science, impact, challenges) in a sequence of developments, each adding a new layer to the story.

- Example 2: In a crime investigation report, the Christmas tree structure could suspensefully unveil successive discoveries and revelations, building intrigue.

Organic[edit]

Jon Franklin's organic structure is characterized by a series of visual images creating a cinematic narrative. It involves "foci" for action depiction and transitions for time, mood, subject, and character establishment.[1]

- Example 1: A travel article might describe vivid scenes from a market, transitioning into discussions about cultural significance and then focusing on individual stories.

- Example 2: In a documentary review, the organic structure could use visual storytelling techniques to analyze the film's narrative style, cinematography, and thematic elements.

Five-Boxes[edit]

Developed by Rick Bragg, this structure includes five parts: a captivating hook, a nut graph, a secondary lead, detailed support, and a strong concluding "kicker."[1]

- Example 1: An environmental piece might start with a startling fact about climate change, summarize the issue, delve into specific effects and responses, and end with a powerful call to action.

- Example 2: In a sports feature article, the five-boxes structure could begin with an intriguing sports anecdote, followed by background information, player profiles, and game analysis, and conclude with a memorable moment from the match.

See also[edit]

References[edit]

- ^ a b c d e f g Naveed Saleh (14 January 2014). The complete guide to article writing. F+W Media. ISBN 9781599637341.[permanent dead link] Also see "Crafting a strong feature article" in Writer's Digest, November/December 2015.

- ^ "Associated Press Stylebook". www.apstylebook.com. Archived from the original on 9 November 2023. Retrieved 12 November 2023.

- ^ a b Debora Halpern Wenger (6 August 2014). Advancing the story: journalism in a multimedia world. CQ Press. ISBN 9781483370460. Archived from the original on 12 November 2023. Retrieved 21 October 2015.

- ^ a b "Telling the story". U.S. Department of State Handbook of Independent Journalism. 11 April 2008. Archived from the original on 18 December 2016. Retrieved 24 October 2015.

- ^ "Journalism writing rubrics: opinion story rubric" (PDF). Plain Local Schools. Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 24 October 2015.