Catastrophe du Boël

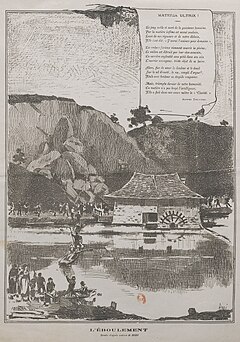

An illustration entitled L'éboulement (The landslide) and representing the Boël disaster. | |

| Date | June 6, 1884 |

|---|---|

| Location | Le Boël in Bruz (Ille-et-Vilaine, France) |

| Coordinates | 47°59′34″N 01°45′15″W / 47.99278°N 1.75417°W |

| Deaths | 8 |

The catastrophe du Boël (disaster of Boël) was a landslide that occurred on June 6, 1884, in a quarry at a place named Le Boël in Bruz, Ille-et-Vilaine, in the west of France. The landslide killed eight people including two children. Groundwater that weakened the cliff and damage caused by explosives used to remove red shale (found as a construction material in the local churches) from the quarry were the principal causes of the accident. The search to recover the bodies took five days.

At the time, the event left its mark, probably because of the death of the children and because it impacted different social classes. Editors of several newspapers from Rennes collaborated and sold a magazine at 50 cents apiece to benefit the victims. Donation campaigns were also carried out by the local press.

Background[edit]

Le Boël is a place situated along the Vilaine River, to the southwest of Rennes, between the municipalities of Guichen and Bruz.[1]

At the end of the 19th century, the quarries in the area worked to extract red shale which can be found in the masonry of local churches,[1] including the churches of Rheu, Saint-Erblon, L'Hermitage, Cesson-Sévigné and La Chapelle-des-Fougeretz.[2] More precisely, it is a siltstone, a micaceous purple Le Boël type which are "massive rocks, sometimes with an eyed structure associated with bioturbation, roughly cut by a fractured schistosity", the red facies being due to the alteration of the chlorite to hematite.[3] To extract this rock, the quarry workers used explosives on the side of a cliff, often risking their lives.[2]

The river Vilaine served as a route to transport the extracted rock by boat[1] and the river traffic was dense.[2] In 1881, more than 61,500 metric tons of freight transported via 2,849 ships passed through the lock at Boël.[2] During this period, due to the numerous town planning works carried out in Rennes, then headed by the mayor Edgard Le Bastard, the General Council of Ille-et-Vilaine saw an 80% increase in river traffic.[2]

At the time, about twenty quarry workers worked in the quarry of Boël, near the mill of Boël.[4] The quarry was the property of a Mr. Ferrand, the miller of Boël, who bought it two or three months before the incident.[5] The workers were under the orders of Monsieur de la Bourdonnaye, châtelain and mayor of Laillé.[4] They earned about two francs per cubic meter of material.[6] According to the tradition of the country, to work faster and earn more money, the quarrymen had the habit of attacking the rock from below rather than mining it from the top layer.[6]

Landslide[edit]

Friday June 6, 1884, was a day whose stormy heat was accompanied by heavy rain.[2] At the end of the morning, near 11 AM, seven quarry workers who were working in the quarry decided to rest a little and, soon after, they were joined by the miller's stepson who brought cider.[7] In search of relief on this hot morning, the eight people decided to settle in the shade of a huge rock that formed a dome.[7] Shortly after, "a crack followed by a tear was heard, then a roll similar to the sound of thunder."[2] Behind the mill located below, near the lock, large blocks of rock broke away from the cliff, crushing the quarry workers who were resting and drinking.[1] The few people who were nearby, as well as quarry workers in the area who were quick to join them, quickly started looking for possible survivors.[1]

According to the June 8, 1884 edition of Le Petit Rennais hebdomadaire, the timing of the incident was different. In fact, during this season, the workers generally worked from 5 AM and took a break around 8 AM to rest and eat.[4] It was then that the landslide would have taken place and, after the alarm was immediately given, the rescue work would have started around 9 AM.[4]

The first bodies to be freed were that of Renaud shortly after the landslide and that of the Chérel Jr. around 7 PM.[5] The search stopped after dark and resumed the next day at dawn.[5] The bodies of Marchand and Josset were found that day before that of Chérel Sr., whose body was removed around 8 PM.[5] On the following days, the excavation work continued and the bodies of Robert, Morin and Grégoire were cleared of the rubble on Sunday evening, Monday and Tuesday morning, respectively.[5]

Victims[edit]

During the disaster, different social classes were affected.[1] Among the victims were children and adults, but also workers and a family member of the quarry owner.[1]

| First Name | Last Name | Age | Other Information |

|---|---|---|---|

| Joseph | Chérel | 57[6] or 58[5] | Quarry team leader.[6] Left a widow and four children.[5] |

| Joseph | Chérel | 27[5] | Quarry worker, single, son of Joseph Chérel also deceased.[6] |

| Alexis | Grégoire | 17[5] or 18[6] | |

| Jules | Josset | 49[5] or 56[6] | Quarry worker.[6] Widower, two children.[5] |

| Jean-Marie | Marchand | 32[5] | Quarry worker. Left a woman and a child of 7 years old.[6] |

| Joseph | Morin | 13[5] or 14[6] | Stepson of Mr. Ferrand, miller of Boël and owner of the quarry.[4] Came to have fun[5] and brought cider to the workers.[7] |

| Pierre-Marie | Renaud | 13[5] or 14[6] | Son of the teamster of the Boël mill.[5] |

| Jean-Marie | Robert | 29[5] | Quarry worker.[6] Left a woman and three children (one of whom was very young or about to be born.)[6][5] |

Causes[edit]

Groundwater was a danger for the quarry workers because it weakened the cliff.[2] It would thus be one of the causes of the disaster, in addition to the damage caused by the explosives used to extract the shale.[2] Also, around 7:45 AM on the day of the incident, the quarry team leader had a borehole loaded, but although the wick was lit, there was no explosion.[4] It is unclear, however, if the quarry workers loaded a new charge recklessly into the same hole or if a second borehole was put into action.[4]

Aftermath[edit]

The funeral for the five deceased that were discovered on Friday and Saturday took place in the church of the village of Pont-Réan on Sunday, June 8.[6] For the last three victims whose bodies were found between Sunday evening and Tuesday morning,[5] their lives were celebrated in the same place on Tuesday.[6] The death certificates were drawn up at the town hall of Bruz, as the Boël quarry is located in Bruz.[5]

On June 29, it was announced in the press that the Minister of the Interior, Pierre Waldeck-Rousseau, sent 500 francs so that the sum could be distributed among the families of the victims.[8] Various initiatives to help the families of the deceased were made. For example, donation campaigns were carried out by the local press to help them.[5][6] In Rennes, children forfeit the amount they obtained from distribution at their primary municipal school so that a sum of 20 francs could be paid in their name.[9]

In addition, the editors of various Rennes newspapers collaborated to produce a collection of poems with an account of the disaster and engravings, in a single issue, "for the benefit of the victims of the Boël disaster."[1] Collaboration occurred between the republican, monarchist and theatrical press.[10] In support of this initiative, the printers provided the material free of charge.[10] This illustrated newspaper was put on sale at the price of 50 cents[2] on Sunday July 6, 1884.[10]

In June 1891, another landslide killed six workers, who died from being crushed under a 30 metric ton block of rock.[1] However, this incident did not elicit the same response as the incident of 1884, probably due to the fact that children and other social classes were not affected.[1]

References[edit]

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Erwan Le Gall (2013). "1884 : la catastrophe du Boël". En Envor. Retrieved 2020-03-01.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Erwan Le Gall (February 2020). "Catastrophe au Boël". Rennes Métropole magazine. pp. 48–49. Archived from the original on 2020-02-04. Retrieved March 1, 2020.

- ^ F. Trautmann; J.F. Becq-Giraudon; A. Carn (1994). Bureau de recherches géologiques et minières (ed.). Notice explicative de la feuille de Janzé au 1/50 000e (PDF). Orléans. pp. 12–13. ISBN 2-7159-1353-2. Retrieved February 14, 2020.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ a b c d e f g "La catastrophe du Boël". Le Petit Rennais hebdomadaire. June 8, 1884. Archived from the original on 2022-01-02. Retrieved March 1, 2020.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u "La catastrophe du Boële". Courrier de Rennes. June 14, 1884. Retrieved 2020-02-06.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q "La catastrophe du Boël". Le Petit Rennais hebdomadaire. June 15, 1884. Retrieved 2020-02-05.

- ^ a b c Louis Baume (July 6, 1884). La carrière du Boël. La Presse rennaise. p. 1. Retrieved 2020-02-05.

- ^ "Les victimes du Boël". Le Petit Rennais hebdomadaire. June 29, 1884. Archived from the original on 2022-01-02. Retrieved February 5, 2020.

- ^ "Nouvelles locales et régionales : Rennes". Le Petit Rennais hebdomadaire. August 3, 1884. Retrieved February 6, 2020.

- ^ a b c "Avis au public". Le Petit Rennais hebdomadaire. July 5, 1884. Retrieved February 5, 2020.