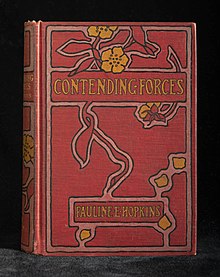

Contending Forces

| |

| Author | Pauline Hopkins |

|---|---|

| Illustrator | R. Emmett Owen |

| Publisher | The Colored Co-operative Publishing Co. |

Publication date | 1900 |

Contending Forces: A Romance Illustrative of Negro Life North and South is Pauline Hopkins' first major work and debut novel, published in 1900. Contending Forces focuses on African American families in post-Civil War American society. Hopkins, a child of free parents of color, imprinted her "own evasive and unsettling maternal family history, which linked her to the Atlantic slave trade, the West Indies, and the American South",[1] providing a vivid portrayal of the shared struggles endured by both enslaved and free individuals during that time period.

The preface written by Hopkins provides insights into her motivations and thematic concerns. Here, she expresses a strong desire to uplift her race and "raise the stigma of degradation"[2] associated with African Americans. Hopkins highlights her commitment to using a romance plot to explore social and racial themes, offering the story of an educated and resilient African American family overcoming racial barriers to achieve success. Ultimately, Hopkins expresses her admiration for her race's achievements and her desire to encourage and strengthen African American communities through her writing.

Contending Forces was published in 1900 by the Colored Co-operative Publishing Company in Boston, Massachusetts. The novel's setting mostly revolves around the city of Boston, painting a rich portrayal of African American life during this period.

Plot summary[edit]

Contending Forces begins with an introduction to Charles Montfort, a successful slave-owner who has moved to North Carolina from Bermuda with his family—sons Charles Jr. and Jesse, and his wife Grace—and his slaves. He plans to slowly free his slaves, against the wishes of the local townspeople. Upon arriving in North Carolina, rumors spread that Grace Montfort has African American descent. Montfort discusses this with his friend Anson Pollack, the man from whom he had purchased his land. Unbeknownst to the Montfort family, Pollack devises a plan alongside the other townspeople to kill Montfort and destroy his property. Though most of the townspeople are fueled by anger at Montfort's desire to free his slaves, Pollack is also embittered by Grace Montfort's rejection of him. On a beautiful day soon afterward, Pollack, followed by several other men, shoots Montfort dead, and ties Grace Montfort up, whipping her. She disappears shortly after, and the text implies that she commits suicide by drowning in the Pamlico Sound. Pollack takes ownership of the Montfort sons, selling Charles Jr. to a mineralogist. Jesse, sent on an errand by Pollack, escapes and flees to Boston, Massachusetts. There, he finds refuge at the house of Mr. Whitfield, a "negro in Exeter who could and would help the fugitive".[2] While waiting for Mr. Whitfield, he rocks the cradle of a crying baby, Elizabeth Whitfield, whom he marries fifteen years later, and has a large family with.

In the following years, the reader is introduced to Ma Smith, the daughter of Jesse Montfort and Elizabeth Whitfield. A widow herself, Ma Smith cares for her two children, Will and Dora Smith, sustaining their family through their lodging house business. The chapter begins with Dora eagerly preparing for a new guest. Will and John Langley, a family friend and Dora's romantic interest, ask questions about the new tenant, and Dora confidently responds by asserting her belief that Will will fall in love with her. The new tenant, Sappho Clark, arrives but keeps to herself. Dora and Sappho quickly become friends, and Dora is impressed by Sappho's diligent work as a typist. Will soon submits to Dora's prophecy, finding himself drawn to Sappho, even in her absence. While Sappho is reserved about her past, she gradually integrates into the community, showcasing her musical talent by playing the organ at church.

Ma Smith organizes a fair to collect revenue for the church. Local women gather in a sewing circle to arrange the event and discuss women's roles in society, debating the morality of female decisions concerning virtue and desire. Before the big event, Will and Sappho hint at their romantic feelings for each other: Will builds Sappho a fire every day, while she helps mend his socks. Sappho recognizes their love for one another but admits that she cannot be with him, and so she cannot ever be happy. At the fair, there is a fortune teller act, featuring a little boy named Alphonse, a child with mulatto features, who Sappho takes a great interest in and places on her lap. Meanwhile, Dora is caught between her childhood friend Dr. Arthur Lewis and Langley. Langley, in turn, flirts with Sappho, and upon her rejection, he challenges her and implies that she is Alphonse's mother, which she quickly denies before excusing herself. Despite these moments of tension, the fair is ultimately successful and enjoyable for all those who attend.

Langley's attraction for Sappho grows, and he believes he can persuade her to have an affair with him, despite his impending marriage to Dora. Meanwhile, a black man was lynched after being accused of raping a white woman, sparking a heated controversy around town. Langley is up for a position as City Solicitor of the American Colored League and promises to suppress any outspoken passion at the upcoming indignation meeting. At the meeting, speakers of different political standings voiced their opinions regarding the African American presence in their town, and whether political agitation in the North would improve or worsen the situation for African Americans in the South. Speaker Lycurgus Sawyer tells a personal story about being born to free African Americans and witnessing the murder of his own family. He was saved by Monsieur Beaubean and became paternally loving of Beaubean's daughter, Mabelle. Mabelle's evil white, half-uncle kidnapped raped her, and deserted her in a whorehouse. After Mabelle was found pregnant, a confrontation occurred between Monsieur Beaubean and the half-uncle, which lead to the burning down of the Beaubean household, killing all but Sawyer and Mabelle. Sawyer took Mabelle to a convent, where he is told she died in childbirth, to his devastation. Sawyer thus believes that while peace is possible, justice is also necessary. During this emotional reflection, Langley notices that Sappho faints, and is taken outside. After Sawyer's speech, Will argues that African Americans are fit for higher education, and should pursue better occupations. He points out that lynching is common and justified by slight suspicion of African American violence, whereas white violence against African Americans invokes no punishment or consequence. The audience is deeply touched by Will's speech.

Langley visits the fortune teller from the fair, and hears Sappho leaving her, addressing her as "Aunt Sally." The fortune teller reveals that Langley will have a bleak future, much to his dismay. At the Canterbury Club Dinner, Will is seated next to Mr. Withington, who seeks a deeper understanding of the race conflict. The men discuss the conflict further, and Withington promises to do what he can. He gives Langley his business card, which reads: Charles Montfort, Withington. On Easter Sunday, Langley is infatuated with Sappho and ignores Dora. However, Sappho and Will meet in the garden and declare their love for each other. They wait to tell their family of their engagement the following day. Sappho's bliss is soon disrupted, however, when Langley enters Sappho's room uninvited and reveals that he knows she is truly Mabelle Beaubean. He threatens to expose her past to Will unless she agrees to marry him. Sappho is distraught, but refuses Langley, and leaves Ma Smith's home during the night. When Will awakens the next morning, excited to share the news of his engagement, Dora shows him the letter Sappho left behind, explaining the truth of her past, and Langley's threat. Dora decides to break her engagement to Langley, and Will leaves to confront him, leading to a physical fight that marks the end of their friendship.

Sappho goes to her Aunt Sally and declares that she wants to take back her son Alphonse and begin a new life as his mother. With Alphonse, she leaves for New Orleans and is taken in by a convent. Her identity is protected as Sappho Clark, and she is welcomed as a young widow. While Alphonse stays at the orphanage, Sappho works as a governess for two years. Her employer, widower Monsieur Louis, asks her to marry him, and she asks for two weeks to consider his proposal. Meanwhile, Will graduates from Harvard and Dora marries Dr. Arthur Lewis. Charles Montfort-Withington visits Will, and discovers his connection to the family, revealing his unsuccessful attempts to fine Jesse. It is also revealed that John Langley is a descendant of Anson Pollack. The Supreme Court identifies Ma Smith as the last representative of the heirs of Jesse Montfort, granting her $150,000.

Will visits Dora in New Orleans, and they attend Easter Sunday at the same convent Sappho coincidentally arrived at years ago. Will recognizes Alphonse, and rushes to find Sappho, which he does. They reunite, and he forgives her for running off and not trusting in him to accept her. Monsieur Louis, though disappointed that Sappho will not marry him, understands and is happy for the couple. Langley's future is revealed, as he dies alone, matching the fortune told to him by "Aunt Sally". The text ends with the Smith family, including Sappho and Alphonse, happy together.

Themes[edit]

Feminism[edit]

Sappho Clark, protagonist of Contending Forces, has often been discussed as a literary representative of feminism.

A victim of sexual abuse, Sappho Clark redefines what is means to be a mother, as she is separated from her illegitimate child for a large portion of the text. Allison Berg notes that Hopkins' "intervention in these ideologies [of what nineteenth-century, white notions of True Womanhood is] thus involves not only telling the ‘real' story of black mothers . . . but also interrogating contemporary racial and sexual discourses that contributed to black women's subjugation and limited their efficacy and mothers,"[3] pointing out the intersectionality of Hopkins' embedded feminism, as she describes the problems of discrimination against gender, class, race, and so forth. Berg argues that through Hopkins' reconstruction of "motherhood," she also affirms Sappho's right to motherhood outside of marriage,[3] opening possibilities for women's rights during a patriarchal, racially unsettling time.

Hopkins' decision to design an ending in which Sappho is able to overcome the rape of her half-uncle and threats by John Langley, and to marry Will Smith while reclaiming her son, has also allowed several scholars to view this novel as a pro-feminist text. Sappho is often read as a Christ-figure: she is forgiven, redeemed, and reborn by her endured hardships.[4] Hopkins' allusions to religion within the text has arguably allowed readers to see the biblically cited injustice in judging Sappho, and others like Sappho, for her forced "impurity" without understanding the cause of this sexual "impurity."[5] Though Sappho, as an African American woman, is vulnerable to her society as a result of her race and gender, she asserts black female power,[3] providing an example for the feminist discussion of critical race theory and intersectionality in the novel.

Racism[edit]

Throughout the novel, examples of racism serve as poignant reminders of the widespread injustice and discrimination that African Americans faced in the late 19th century. Racism affects the main character, Sappho Clark, in many ways that shape her experiences and challenge her identity. Sappho's journey highlights the systematic racism embedded in society, from her abduction and rape by her white uncle and forced labor to the job discrimination and social isolation she faces. Furthermore, Hopkins' intention to "remove the stigma, the mark of shame, from the collective flesh of her race" challenges the legacy of racial stigma while also empowering African Americans by rejecting dominant narratives of shame and inferiority.[4] She explores how past traumas continue to shape the person's identity in the post-Reconstruction era. Hortense Spillers observes that many critics fail to identify that the female slave "is not only the target of rape," but also "the topic of specifically externalized acts of torture"[4] executed by other males. From the beginning, readers are introduced to Grace Montfort, a woman who is allegedly of African American ancestry and ultimately faces tragedy. In a short amount of time, she is taken down and faces violence from a white man. Sappho and Grace's stories highlight how racism and gender inequality are intertwined, and how African American women are more likely to both sexual assaults and acts of violence motivated by race.

Modern reception[edit]

Contending Forces garnered mixed reviews from modern readers, especially in regard to the issues with gender embedded within the novel. Though Sappho Clark is widely regarded as a feminist character, the debate surrounding her position as a victim has led some to question the feminist nature of the text. Poet Gwendolyn Brooks wrote that Hopkins' novels revealed the author to be "a brain-washed slave [who] reveres the modes and idolatries of the master", a position which has generated much debate.[6]

While there are conflicting interpretations of the treatment of women in the text, contemporary critics often praise Hopkins' ability to "raise the stigma" of her race.[4] For example, Houston Baker writes that the novel "insists on the rights of Black Americans to be fully integrated subjects, politically and economically",[6] establishing a complex discussion on the rights and abilities of African Americans, particularly African American women, in post-Civil War society.

The novel has also been regarded as a representation of the necessary political reaction to the treatment of African Americans. Thomas Cassidy calls the novel a polemic, arguing that "it has been constructed to convince its readers that the widespread lynching and raping of black people around the turn of the century constituted political terrorism which had to be combated by political means".[6]

References[edit]

- ^ Brown, Lois (2008). Pauline Elizabeth Hopkins: Black Daughter of the Revolution. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press.

- ^ a b Hopkins, Pauline E. (1991). Contending Forces: A Romance Illustrative of Negro Life North and South. Oxford University Press.

- ^ a b c Berg, Allison (1996). "Reconstructing Motherhood: Pauline Hopkins' "Contending Forces."". Studies in American Fiction (2): 131–150.

- ^ a b c d Putzi, Jennifer (2004). ""Raising the Stigma": Black Womanhood and the Marked Body in Pauline Hopkins's "Contending Forces."". College Literature (2): 1–21.

- ^ Brooks, Kristina (1996). "New Woman, Fallen Woman: The Crisis of Reputation in Turn-Of-The- Century Novels by Pauline Hopkins and Edith Wharton". Legacy (2): 91–112.

- ^ a b c Cassidy, Thomas (1998). "Contending Contexts: Pauline Hopkins's Contending Forces". African American Review (4): 661–672.

External links[edit]

The full text of Contending Forces at Wikisource

The full text of Contending Forces at Wikisource