Haras National d'Hennebont

| Haras National d'Hennebont | |

|---|---|

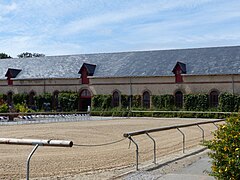

Entrance to the Haras National d'Hennebont. | |

| |

| Record height | |

| General information | |

| Address | 35 rue de la Bergerie, 56700 Hennebont |

| Country | France |

| Year(s) built | 1856 |

| Owner | Syndicat Mixte |

The Haras National d'Hennebont (English: Hennebont National Stud) is one of five equestrian centers in the French region of Brittany. It was created in 1856 in Hennebont, Morbihan, around the former Abbey of La Joie, as a result of an exchange with the Abbey of Notre-Dame de Langonnet. Inaugurated by Napoleon III on August 15, 1858, it was classified as a historic monument in 1995.

The Haras National d'Hennebont has a long tradition of public stallion breeding, acquiring and making available stallions, mainly of the Breton breed, to breeders in its district. This historic function gradually came to an end between 2007 and 2016, with the transition from state management to that of a Syndicat Mixte. The national equestrian society housed there, founded in 1964, will cease operations in 2019.

Now mainly devoted to tourism, the Haras National features a horse discovery area and a driving school, and organizes numerous shows and events throughout the year, including a Christmas market.

History[edit]

Under the Ancien régime, there were always more stallion depots in the north of Brittany than in the south.[1] The Haras system was notoriously inefficient in Brittany, not least because breeders were looking for more diverse stallions, and remained attached to the local Breton bidet breed.[2] Under the Consulate, in 1803, Chaptal looked for locations to establish a new stallion depot in Morbihan: the Josselin Castle, the Abbey of Saint-Jean-des-Prés, the Crévy Castle, the Truscat Castle, and the Ursulines' enclosure in Ploërmel were all considered, before a choice was made for the Abbey of Langonnet, in 1806.[1]

On November 12, 1842, the districts of Brittany were defined on the basis of these two stud farms.[3] As the Langonnet depot was poorly served by narrow, impassable roads, a new location was sought from 1849 onwards.[4][5][6][7] The Abbey de la Joie, in Hennebont, was one of the proposed sites.[8]

Establishment and inauguration[edit]

A decree issued on November 10, 1856 authorized the transfer of the Haras National from Langonnet to Hennebont, on a 5-hectare site around the Abbey of La Joie. The site exchange was signed by the Prefect of Morbihan on December 31.[8][9] The exchange was concluded between the congregation of the Pères du Saint-Esprit and the French state: the congregation wished to settle in Langonnet. To make the exchange with Hennebont, owned by Sieur Queron, more equitable, the congregation pays for the construction of a stable for 32 stallions, an enclosing wall, a gate and two pavilions, one for the janitors and the other for the head groom.[6][10] The transfer of the stud is managed by its director, Mr. Drieu.[11] This operation was accompanied by a re-division of the Breton districts, with the Haras National de Lamballe losing the management of Ille-et-Vilaine to Hennebont, in exchange for the northern part of Finistère.[6][12] As Gérard Guillotel notes, this division seems illogical, and penalizes breeders in Ille-et-Vilaine, who are geographically closer to Lamballe than to Hennebont: it was justified at the time by the future development of the Haras National de Lamballe.[13]

The law ratifying the exchange was signed by Napoleon III on May 19, 1857.[14][15] The stud became operational that same year.[6] The initial entrance was from the banks of the Blavet, via the conciergerie pavilion.[8]

A forge was built in 1858.[6][15] The official inauguration took place one year after the opening, in the presence of Napoleon III and the Empress, on August 15, 1858, Saint-Napoleon's Day. The facades were whitewashed for the occasion.[16] The mayor of Hennebont, Olivier Levier, thanks the Emperor in his speech.[8][11] A full-length portrait of Napoleon III, wearing the imperial mantle, is kept as a souvenir in stable no. 1.[17][15]

Up to the beginning of the 20th century[edit]

Work is carried out to increase the capacity of the stud: stables numbers 2, 3 and 4 become operational in 1880.[6][19]

Initially focused on breeding draft horses, the Haras National d'Hennebont acquires Anglo-Norman and Norfolk Trotter stallions, with the aim of lightening the Breton breed through crossbreeding.[17][20] Among his initial stallions is the Norfolk Trotter Grey Shales, transferred from Langonnet.[6] The "missions to the Orient" led to the arrival of ten Arabian thoroughbred stallions at Hennebont between 1874 and 1892.[20] The establishment's first director began promoting the Cornouaille Postier horse, the Morbihan Petit draft, and a heavier draft horse in Ille-et-Vilaine. The Odet basin (between Scaër and Quimper), the Redon region and northern Ille-et-Vilaine all have a tradition of breeding horses for cavalry. In 1900, the Haras National d'Hennebont no longer had any Arabian or Anglo-Arabian stallions, having 148 stallions, mostly half-bloods, for 36 Postiers and 15 Breton draft stallions, serving around 12,000 mares in its district.[21][22]

From 1901 to the World War II[edit]

In 1901, a certain Mr. Perrin sold the Haras National a hectare of land to the north. This enabled the construction of stables numbers 5, 6 and 7. The director's and staff quarters were built in 1902. The third stud officer arrived in 1907, when the "supervisor's" house was built; the assistant director arrived the following year, and an infirmary was also created in 1908.[6][19]

Between 1900 and 1914, the number of half-blood horses declined, in favor of Postier and Trait Breton. At the same time, the Breton bidet tended to disappear.[20] In 1914, the stud had 262 breeding stallions.[21]

In 1914, a 4-year-old mare from the Corlay line, Caroline, bred by the Haras National d'Hennebont, won first prize at the Concours Central Hippique de Paris, as did her breeder, Mr. Roux from Scaër.[20] Particular attention was paid to maintaining horse births during the World War I,[22] in particular the production of the Breton Postier, the artillery horse par excellence.[21] After the armistice, the Haras National d'Hennebont employed over 100 staff.[22][23] Agricultural needs lead to an increase in the number of draft stallions, as well as imports of Ardennais stallions, although there are fewer of them than at Lamballe.[21]

-

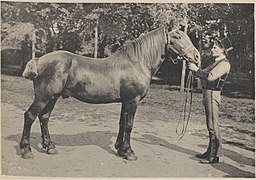

Artisan, Breton horse from Landivisiau, sold to the Haras National in 1927.

On November 8, 1920, a further 7 hectares were acquired from Mr. Perrin, including the lower part of the abbey with its 17th-century buildings and outbuildings, for the total sum of 302,000 francs.[6][8][24] In 1923, the Haras lost its Breton stallion purchasing centers in Carhaix and Combourg.[21] The following year, 20,917 mares were covered in the Hennebont district.[25] In 1927, the Hennebont site had its largest number of stallions, 293, making it the 4th largest in France. More than half of the stallions are listed as Breton Postier, while 132 are Breton Trait, following the division of the breed's studbook in 1926. There were 93 employees at the time. In 1929, Hennebont had no saddle stallions.[26] The spread of motorization led to a decline in the Haras' activities in the years leading up to the World War II.[21]

During the World War II[edit]

In 1939, the mobilization of a certain number of grooms led to additional work for those who had not been mobilized by the needs of the war.[27] However, the stud's director, Mr. Poujols de Molliens, managed to maintain the equestrian activity on site throughout the war years.[21] The wartime situation reinforced the idea of "cultural breeding", designed to resist defeat and then German occupation. The continued presence of Mr. Poujols de Molliens, who held the post for 15 years, ensured a certain stability.[13]

German troops reached Hennebont in June 1940. Around 4,000 prisoners of war were held on the Hennebont site until 1942, a few managing to escape by wearing the uniforms of grooms.[28] In 1943, the Germans occupied almost the entire site, setting up an ammunition depot and a food depot. The latter was regularly looted by grooms in contact with the French Resistance (including Haras supervisor Michel de Kersabiec), who knew the German patrol schedules.[29] An anti-Nazi German soldier helps these grooms, enabling a French officer to reach England, with a special message sent to the Resistance fighters at the Haras National d'Hennebont via the BBC. Hennebont was liberated by the Allied forces on August 16, 1944, thanks to sabotage of the Blavet bridge, which prevented the German garrison stationed at the Haras from reaching the Lorient pocket. The German soldiers at the Haras surrendered, after demolishing the director's house with shellfire from Montagne du Salut.[30]

When the Lorient pocket surrendered on May 10, 1945, the Haras National d'Hennebont was transformed into a German prisoner-of-war camp.[31] After the war, the stud almost no longer housed horses, but soon returned to its traditional functions.[28][32]

From 1945 to 2007[edit]

The decline of the draft horse accelerated after 1945, although it was relatively slow and gradual in Brittany, leading to a loss of motivation among breeders.[13] Foreign missions (Italy, Spain, Japan...) kept the Breton breed alive.[21] The conversion of Breton horse breeding to meat production is helping to maintain the breed's numbers.[33] Director M. Gendry began converting the breeding program to this end as early as 1946. From 1952, Marcilhacy continued this policy. The system of rolling trucks became widespread, to bring stallions to breeders who had difficulty moving their mares to the stud farm or breeding station. Since the 1960s, livestock premiums have encouraged breeders in the Hennebont district to keep draft horses. In 1954, over a period of 17 years, a breeder stallion, Gerfaut, assigned to the Bannalec station in Finistère, had a lasting influence on the Breton breed in the Hennebont district, through cross-breeding with postal mares.[34]

The Société Hippique Nationale d'Hennebont opened in 1964, marking the establishment's move towards equestrian sport.[35] Mr. de Dieuleveult took over as director in 1965, favoring racehorses and sport horses and increasing the number of stallions.[13] His three successors continued in this vein, while maintaining a large Breton herd.[34] In 1970, with 217 stallions, Hennebont was one of France's largest stallion depots; in 1973, twelve bloodstock stallions were stationed there.[13]

The stud was also one of the pioneers in the use of equine artificial insemination in France, the technique being tested on its draft stallions as early as 1981.[36] In 1985, it sent a huge Breton butcher-type breeding stallion, named Oscar, to the Bannalec station.[37] The great storm of October 16, 1987 severely damaged the site.[38]

In 1993, Hennebont had 34 employees and 12 breeding stations in its district: Fouesnant, Pleyben, Quimper, Gourin, Malestroit, Combourg, La Guerche-de-Bretagne, Lohéac, Plerguer, Saint-Aubin-du-Cormier and Vitré. Its national equestrian society has 45 horses and ponies at its disposal.[38] The Haras National d'Hennebont also manages some twenty horse-racing societies, and 22 racing societies in its area, the most prestigious of which is Dinard.[13]

Transfer to joint management[edit]

Since 2007, the Syndicat Mixte du Haras national d'Hennebont has managed the site's buildings and trees, with the exception of the Abbey de la Joie and the Pavillon de la Porterie.[39] The syndicat mixte is made up of the Brittany region, the Morbihan department, the Lorient Agglomération and the town of Hennebont.[40]

On October 15, 2015, the French Horse and Riding Institute (Institut français du cheval et de l'équitation, IFCE by its acronym in French) announced that the stud farm would be put up for sale in January 2016.[41][42] In April 2016, the town of Hennebont and Lorient Agglomération officially announced that they had negotiated an agreement with the IFCE to become owners of the entire site, comprising the 32 buildings, including the Abbey of La Joie, spread over 23 hectares, for 800,000 euros (750,000 euros according to the La France agricole website[43]), on condition that the partners in the syndicat mixte undertake to help manage the site.[44] The transfer of ownership will take place before the end of 2016. The planned project is to perpetuate horse-related activities, making the stud farm a tourist attraction in the Lorient basin.[45]

In September 2018, the stud will host Équi-meeting, dedicated to equine mediation. In August 2019, the Haras d'Hennebont will welcome a Japanese delegation interested in Breton draft breeding.[46]

The Société Hippique Nationale closes in September 2019, after 55 years of existence:[47] its lease has not been renewed, forcing it to vacate the premises by the end of 2019 at the latest.[48][49] The fate of the association's 50 horses and 4 employees remains unknown.[50]

Site description[edit]

The Haras National d'Hennebont is located on a 23-hectare site, surrounded by a 3.2-km-long wall.[51] The official address is 35, rue de la Bergerie, but vehicular access is via 1, rue Victor-Hugo.[52]

Built heritage[edit]

The stud boasts a very rich built heritage,[53] with a total of 32 buildings, including seven stables, three manor houses and a forge, for a total built area of around 10,000 m2. This built heritage is managed in collaboration with the Architect des Bâtiments de France.[51] The Haras porterie, nicknamed the "house of confessors", is considered remarkable.[53] This former janitor's lodge stands on the banks of the Blavet River.[54]

The buildings of the Haras National d'Hennebont, with the exception of the one built in 1986 and the buildings of the Abbey of La Joie (otherwise protected[55]), were listed as historic monuments by decree on November 6, 1995.[56]

-

Stable no. 1, home to the horse discovery area.

-

Horse-drawn vehicle shed.

-

Porterie of the former Abbey de la Joie, now an artists' residence.

-

Logis abbatial de l'ancienne abbaye de la Joie.

Equestrian and horse-drawn heritage[edit]

The Hennebont Saddlery of Honor includes a Moroccan saddle with gilded embroidery.[57] A full-length portrait of Napoleon III, donated after the Haras' inauguration in 1857, is on display in the Horse discovery area, stable no. 1.[58]

Equestrian facilities[edit]

The Haras National d'Hennebont has around 50 stable boxes for horses, three sand arenas with a total surface area of 7,600 m2, a grass competition arena covering 8,800 m2, a 1,500 m2 riding arena, a Havrincourt ring, a covered walker and several paddocks.[59]

-

Stable.

-

Sand quarry, with stables at the back.

Horses[edit]

The Haras National d'Hennebont's regional presence means that the Breton draft horse is a natural breeding specialty.[58][60] The majority of horses on site are therefore draft and half-draft.[61]

In 2013, after the Haras horses opened the traditional parade, the Asturian delegation to the Lorient Interceltic Festival donated a purebred Asturcón pony, named Nordfjior, to the Haras national d'Hennebont.[62]

-

Breton stallion in a stable.

-

Pony in the meadow.

-

Nordfjior, a purebred Asturcón stallion donated to the Haras National d'Hennebont by the Asturian delegation at the 2013 Lorient Interceltic Festival.

In 2014, the stud was home to 25 stallions of all types: draft, saddle, pony and donkey.[63] In 2019, there are only around ten horses on site.

Vegetation[edit]

The entire site is planted with rare species, including some old specimens, such as a lime tree over 200 years old.[54] The 23-hectare park, partially classified as a "protected wooded area", also contains rose bushes in the main courtyard, Monterey pines, whitebeam, Gunnera manicata, ash trees, purple beech and a cedar of Lebanon.[64] Camellias bloom periodically. A fountain sculpted in the shape of a lion's mouth provides water all year round.[53]

In the past, the choice of certain plant species had a practical purpose: hazel was used to make dressage badines, while ash was used for harnessing equipment.[64]

Management[edit]

A number of stud farm directors and inspectors have left their mark on Hennebont's history. According to Gérard Guillotel, the various Haras de Bretagne officers in the second half of the 20th century were very close-knit.[65]

| Name[66][67] | Working years[66][67] | Functions[66][67] |

|---|---|---|

| M. Drieu | 1857–1863 | Depot Director |

| M. de la Motte-Rouge | 1863–1871 | General Inspector and Depot Director |

| M. Quinchez | 1871–1873 | General Inspector and Depot Director |

| M. de Hanivel de Pontchevron | 1879–1881 | General Inspector and Depot Director |

| M. Paulin de Thélin | 1881–1882 | Depot Director |

| M. d'Humières | 1882–1885 | Depot Director |

| M. Hornez | 1885–1886 | General Inspector, general manager and Depot Manager |

| M. las Vignes | 1886–1887 | General Inspector and Depot Director |

| M. de Moulins de Rochefort | 1887–1906 | Depot Director |

| M. Clauzel | 1906–1915 | Depot Director |

| M. du Breil | 1915–1917 | Depot Director |

| M. de Pierre | 1917–1919 | General Inspector, general manager and Depot Manager |

| M. Reynard | 1919–1931 | General Inspector and Depot Director |

| M. Poujols de Molliens | 1931–1946 | General Inspector and Depot Director |

| M. Gendry | 1946–1952 | General Inspector, general manager and Depot Manager |

| M. Marcilhacy | 1952–1965 | Depot Director |

| M. de Dieuleveult | 1952–1965 | General Inspector and Depot Director |

| M. Costes | 1973–1979 | Depot Director |

| M. Dassonville | 1979–1984 | Depot Director |

| M. Legrain | 1984 – ? | Depot Director |

Missions, events and tourism[edit]

The site's activities have evolved over time, and are now mainly focused on tourism, sporting activities and culture, with over 60,000 visitors a year on average, according to Lorient Agglomération.[68] More than 2,500 people will visit the Haras during the 2019 European Heritage Days.[69] Visits include the stables, the forge, the main tack room and the breeding laboratory.[68] All events are managed by Sellor, which also rents out the site for weddings, seminars and cabarets. Equestrian shows are organized from April to December,[70] with more than a hundred shows performed each year, under a big top or outdoors.[68]

The Institut français du cheval et de l'équitation, present on the site, provides equine identification and socio-professional support in the equestrian sector.[71]

Horse discovery area[edit]

A horse discovery area in Brittany, created in 1999,[58][70] is located in the large stable (known as No. 1), presenting the horse and its history. It features interactive museography and videos.[72]

It also hosts temporary exhibitions.[68] In 2001, it hosted an exhibition of black-and-white photographs by Jean-Maurice Colombel, Des chevaux et des hommes bretons,[73] which, according to the daily Le Télégramme, was a great success.[74] For the 2018 Heritage Days, it is hosting an exhibition devoted to costumes and horses.[75] This space attracts around 30,000 visitors a year, according to the Union régionaliste bretonne;[58] 35,000 a year, including 18,000 in the summer season, according to the official website.[70]

Forge workshop[edit]

The Haras National's forge, abandoned since the late 1990s, was reactivated in 2016 to welcome a craftsman who offers courses in cutlery, locksmithing and tools.[76] The workshop also offers creation and repair of metal objects, as well as sharpening.[77]

Driving school[edit]

A driving school at Rédené's Ar Maner ("the manor", in Breton) equestrian center has been up and running since July 2018.[78] The school uses the three riding arenas, the Havrincourt roundabout, the fixed obstacles and the entire park, offering free-riding and long-rein work.[79] Since its installation and until October 2019, around ten people have been trained.[80]

-

Stop and call for attention.

-

Moving

-

Reward at end of work session.

Previously, Hennebont was home to a driving school.[81]

Christmas market[edit]

The Syndicat Mixte organizes an annual Christmas market, which attracts around 10,000 visitors to the Haras d'Hennebont each year, according to the official website. The stud farm is transformed and decorated for the occasion.[82] The 2017 edition covers 700 m2, and welcomes 58 exhibitors, with a free shuttle service provided by the town of Hennebont.[83] In 2018, this Christmas market is one of the last to continue in its geographical area.[84] The 2018 edition was inaugurated by Morbihan Senator Muriel Jourda.[85]

Past events[edit]

The stallion presentation, known as the "grande parade des étalons" and considered a must-attend event in Hennebont, according to Le Télégramme,[86] traditionally took place on the first Sunday in February each year,[87] featuring all stallions supplying semen to the stud, whether working or sport.[88] The last recorded edition took place in 2013.[89] The 2016 competition for broodmares attracted some forty participants.[90]

The Hennebont Horse Week[91] was organized every year in July at the stud farm by the Société Hippique Nationale, offering show jumping competitions and derbies at both pro and amateur levels. The 2019 edition has been cancelled due to the restructuring of the Haras National.[92] Considered by the Ouest-France newspaper and France 3 Bretagne as "the most eagerly awaited event for riders in the Grand Ouest" and "the biggest annual equestrian event in the Brittany region", its July 2018 edition had brought together 2,000 riders over 32 events.[93]

See also[edit]

References[edit]

- ^ a b Guillotel (1986, p. 104)

- ^ Grand Colas & Bourguet-Maurice (1999, p. 18)

- ^ Grand Colas & Bourguet-Maurice (1999, p. 26)

- ^ Guillotel (1986, p. 112)

- ^ Grand Colas & Bourguet-Maurice (1999, p. 20, 28)

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Barbié de Préaudeau (1994, p. 26)

- ^ Guillotel (1986, p. 114)

- ^ a b c d e Guillotel (1986, p. 115)

- ^ Babo (2002, p. 34)

- ^ Grand Colas & Bourguet-Maurice (1999, p. 28)

- ^ a b Grand Colas & Bourguet-Maurice (1999, p. 32)

- ^ Grand Colas & Bourguet-Maurice (1999, p. 30)

- ^ a b c d e f Guillotel (1986, p. 120)

- ^ Bourret, Michèle (1996). Le Patrimoine des communes du Morbihan (in French). Flohic éditions. p. 1101. ISBN 2-84234-009-4.

- ^ a b c "Histoire du site Syndicat Mixte du Haras National d'Hennebont". www.haras-national-hennebont.fr. Retrieved 25 October 2019.

- ^ Grand Colas & Bourguet-Maurice (1999, p. 32, 34)

- ^ a b Guillotel (1986, p. 116)

- ^ Saint-Gal de Pons (1931, p. 31)

- ^ a b Grand Colas & Bourguet-Maurice (1999, p. 34)

- ^ a b c d Guillotel (1986, p. 117)

- ^ a b c d e f g h Barbié de Préaudeau (1994, p. 28)

- ^ a b c Grand Colas & Bourguet-Maurice (1999, p. 36)

- ^ Grand Colas & Bourguet-Maurice (1999, p. 38)

- ^ Saint-Gal de Pons (1931, p. 153)

- ^ Guillotel (1986, p. 118)

- ^ Saint-Gal de Pons (1931, p. 185)

- ^ Grand Colas & Bourguet-Maurice (1999, p. 42)

- ^ a b Grand Colas & Bourguet-Maurice (1999, p. 44)

- ^ Grand Colas & Bourguet-Maurice (1999, p. 46)

- ^ Grand Colas & Bourguet-Maurice (1999, p. 48)

- ^ Grand Colas & Bourguet-Maurice (1999, p. 48-50)

- ^ Grand Colas & Bourguet-Maurice (1999, p. 50)

- ^ Barbié de Préaudeau (1994, p. 28-30)

- ^ a b Barbié de Préaudeau (1994, p. 30)

- ^ "La Société hippique d'Hennebont disparaît du paysage équestre". GrandPrix-replay.com. Retrieved 23 October 2019.

- ^ Insémination artificielle équin (in French). Le Pin-au-Haras. 2009. p. 13. ISBN 978-2-915250-15-2.

- ^ Lizet, Bernadette (2003). "Mastodonte et fil d'acier. L'épopée du cheval breton". La ricerca folklorica Retoriche dell'animalità. Rhétoriques de l'animalité (in French) (48): 59.

- ^ a b Barbié de Préaudeau (1994, p. 32)

- ^ "Croque patrimoine : Le pavillon de la Porterie". Le Télégramme. 2009.

- ^ "Haras. Des travaux d'enrobé pour mieux circuler". Le Télégramme. 2010.

- ^ "Haras. Les sites de Lamballe et d'Hennebont bientôt mis en vente". Le Télégramme. 2015. Retrieved 8 October 2019.

- ^ "Les haras de Lamballe et Hennebont bientôt en vente". France 3 Bretagne. Retrieved 17 November 2019.

- ^ "Cheval : Cinq haras nationaux vendus". La France Agricole (in French). 2016. Retrieved 18 November 2019.

- ^ Schittly, Julie. "Haras : Agglo et Ville achèteront... sous condition". Ouest-France.fr. Retrieved 22 May 2016.

- ^ "L'Abbaye de Joie transformée en pôle hôtelier ?". Ouest-France. 2016. Retrieved 22 May 2016.

- ^ "Haras. Les Japonais apprécient le trait breton". Le Télégramme. 2019. Retrieved 8 October 2019.

- ^ "Hennebont. Après 55 ans de vie, la Société hippique n'est plus". Ouest-France.fr. 2019. Retrieved 8 October 2019.

- ^ "Haras d'Hennebont. Le bureau de la SHN met pied à terre". Le Télégramme. 2019. Retrieved 16 November 2019.

- ^ "Société hippique nationale. La liquidation pour tout horizon". Le Télégramme. 2019. Retrieved 16 November 2019.

- ^ "Haras. La Société Hippique d'Hennebont obligée de cesser ses activités". Ouest-France.fr. 2018. Retrieved 25 October 2019.

- ^ a b "Un patrimoine bâti Syndicat Mixte du Haras National d'Hennebont". www.haras-national-hennebont.fr. Retrieved 25 October 2019.

- ^ Gérard, Laetitia (2015). "Haras national de Hennebont". L’institut français du cheval et de l’équitation. Retrieved 18 November 2019.

- ^ a b c Babo (2002, p. 35)

- ^ a b Grand Colas & Bourguet-Maurice (1999, p. 15)

- ^ "Ancienne abbaye de la Joie". www.pop.culture.gouv.fr. Retrieved 22 October 2019.

- ^ "Haras national d'Hennebont". Ministère français de la Culture.

- ^ "Hennebont – Haras. Visite guidée et spectacle ont attiré bon nombre". Le Télégramme. 2019. Retrieved 16 November 2019.

- ^ a b c d Association bretonne et union régionaliste bretonne (2007). Comptes rendus, procès-verbaux, mémoires (in French). Vol. 133. Presses bretonnes. pp. 28, 211.

- ^ Maury, Vincent. "Louer les infrastructures du Haras national de Hennebont". Les Haras nationaux. Retrieved 17 November 2019.

- ^ Guillot, Frédéric. "Haras national d'Hennebont – Haras nationaux". Les Haras nationaux. Retrieved 18 November 2019.

- ^ Grand Colas & Bourguet-Maurice (1999, p. 11)

- ^ "Haras. Les chevaux ont ouvert la grande parade du Festival". Le Télégramme. 2013. Retrieved 25 October 2019.

- ^ Maury, Vincent (2014). "Visiter et découvrir le Haras national de Hennebont". Les Haras nationaux. Retrieved 18 November 2019.

- ^ a b "Un patrimoine arboré Syndicat Mixte du Haras National d'Hennebont". www.haras-national-hennebont.fr. Retrieved 25 October 2019.

- ^ Guillotel (1986, p. 124)

- ^ a b c Guillotel (1986, p. 125)

- ^ a b c Saint-Gal de Pons (1931, p. 177-178)

- ^ a b c d "[INFOGRAPHIE] Le Haras National d'Hennebont". Lorient Agglomération. 2017. Retrieved 11 November 2019.

- ^ "Hennebont – Journées du patrimoine. Des milliers de visiteurs au haras ce week-end". Le Télégramme. 2019. Retrieved 8 October 2019.

- ^ a b c "Tourisme & Culture Syndicat Mixte du Haras National d'Hennebont". www.haras-national-hennebont.fr. Retrieved 25 October 2019.

- ^ "Formations & Techniques « Syndicat Mixte du Haras National d'Hennebont". www.haras-national-hennebont.fr. Retrieved 25 October 2019.

- ^ "Haras national Hennebont : espace découverte cheval Bretagne". lorient.caplorient.fr. Retrieved 24 October 2019.

- ^ Simon, François (2003). Des chevaux et des hommes Bretons (in French). Editions La Part Commune. p. 4. ISBN 2-84418-050-7.

- ^ "Espace découverte du cheval. Un joli succès qui perdure". Le Télégramme. 2011. Retrieved 24 October 2019.

- ^ "Hennebont. Le patrimoine du cheval en fête dimanche au haras". Ouest-France.fr. 2018. Retrieved 24 October 2019.

- ^ "Hennebont. Au haras, la forge du XVIe revit grâce à Cédric, coutelier". Ouest-France.fr. 2016. Retrieved 25 October 2019.

- ^ "Cédric Lamballais – Coutelier forgeron « Syndicat Mixte du Haras National d'Hennebont". www.haras-national-hennebont.fr. Retrieved 25 October 2019.

- ^ "Le haras accueille désormais une école d'attelage". Ouest-France.fr. 2018. Retrieved 21 October 2019.

- ^ "Ecole d'attelage Ar Maner « Syndicat Mixte du Haras National d'Hennebont". www.haras-national-hennebont.fr. Retrieved 25 October 2019.

- ^ "Hennebont. Ils se forment au métier de meneur au haras". Ouest-France.fr. 2019. Retrieved 16 November 2019.

- ^ Emo, Aurore (2016). "Ouverture de l'école d'attelage HN d'Hennebont". Les Haras nationaux. Retrieved 18 November 2019.

- ^ "Marché de Noël au Haras « Syndicat Mixte du Haras National d'Hennebont". www.haras-national-hennebont.fr. Retrieved 25 October 2019.

- ^ "Hennebont. 11 000 visiteurs attendus au marché de Noël du haras". Ouest-France.fr. 2017. Retrieved 25 October 2019.

- ^ "Haras. Le marché de noël, c'est ce week-end !". Le Télégramme. 2018. Retrieved 25 October 2019.

- ^ "Marché de Noël. Le haras ouvre ses portes". Le Telegramme. 2018. Retrieved 25 October 2019.

- ^ "Haras. Les étalons à la parade aujourd'hui". Le Télégramme. 2011. Retrieved 11 November 2019.

- ^ Grand Colas & Bourguet-Maurice (1999, p. 23)

- ^ "Hennebont. La grande parade des étalons samedi au Haras". Le Télégramme. 2009. Retrieved 11 November 2019.

- ^ "Hennebont. La parade des étalons change de formule". Ouest-France.fr. 2013. Retrieved 11 November 2019.

- ^ "Un concours de poulinières bien suivi au haras". Ouest-France.fr. 2016. Retrieved 17 November 2019.

- ^ "Semaine Hippique d'Hennebont Syndicat Mixte du Haras National d'Hennebont". www.haras-national-hennebont.fr. Retrieved 25 October 2019.

- ^ "SHN. La semaine hippique de juillet annulée". Le Télégramme. 2019. Retrieved 25 October 2019.

- ^ "Hennebont. Du grand spectacle pour la semaine hippique !". Ouest-France.fr. 2018. Retrieved 25 October 2019.

Bibliography[edit]

- Babo, Daniel (2002). Les Haras Nationaux (in French). Paris: Médial éditions. ISBN 2-84730-000-7.

- Barbié de Préaudeau, Philippe (1994). Haras de Bretagne (in French). Édilarge. ISBN 2-7373-1330-9.

- Grand Colas, Josyane; Bourguet-Maurice, Louis (1999). Le haras d'Hennebont (in French). Rennes: Éditions du Quantième. ISBN 2-9511948-2-X.

- Guillotel, Gérard (1986). Les Haras Nationaux (in French). Éditions Lavauzelle.

- Saint-Gal de Pons, Antoine-Auguste (1931). Les Origines du cheval breton (in French). A. Prud'homme.