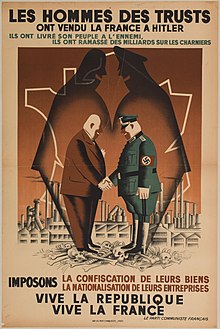

Business collaboration with Nazi Germany

A number of international companies have been accused of having collaborated with Nazi Germany before their home countries' entry into World War II, though it has been debated whether the term "collaboration" is applicable to business dealings outside the context of overt war.[1][who?] Accused companies include General Motors, IT&T, and Eastman Kodak.

American manufacturers[edit]

American companies that had dealings with Nazi Germany included Ford Motor Company,[2][3] Coca-Cola,[4][5] and IBM.[6][7][8] Ford Werke and Ford SAF (Ford's subsidiaries in Germany and France, respectively) produced military vehicles and other equipment for Nazi Germany's war effort. Some of Ford's operations in Germany at the time were run using forced labor. When the U.S. Army liberated the Ford plants in Cologne and Berlin, they found "destitute foreign workers confined behind barbed wire."[9]

Like Swiss banks, American car companies deny helping the Nazi war machine or profiting from forced labor at their German subsidiaries during World War II.[9] "General Motors was far more important to the Nazi war machine than Switzerland," according to Bradford Snell. "The Nazis could have invaded Poland and Russia without Switzerland. They could not have done so without GM."[9] In some cases, GM and Ford agreed to convert their German plants to military production when U.S. government documents show they were still resisting calls for military production in US plants at home.[9]

The Nazis reportedly made extensive use of Hollerith punch card and accounting equipment, and IBM's majority-owned German subsidiary, Deutsche Hollerith Maschinen GmbH (Dehomag), supplied them with this equipment starting in the early 1930s. The equipment was critical to Nazi efforts through ongoing censuses to categorize citizens of both Germany and other nations under Nazi control. The census data enabled the round-up of Jews and other targeted groups, and catalogued their movements through the machinery of the Holocaust, including internment in the concentration camps.[10] Nazi concentration camps operated a Hollerith department called Hollerith Abteilung, which had IBM machines that also included calculating and sorting machines.[11] The history community has long debated whether IBM was complicit in the use of these machines, whether the machines used were IBM branded, and even whether tabulating machines were used for this purpose at all.[12]

In December 1941, when the United States entered the war against Germany, 250 American firms owned more than $450 million of German assets.[13] Major American companies with investments in Germany included General Motors, IT&T, Eastman Kodak, Standard Oil, Singer, International Harvester, Gillette, Coca-Cola, Kraft, Westinghouse, and United Fruit.[13]

General Motors[edit]

General Motors' Opel division, based in Germany, supplied the Nazi Party with vehicles. The head of GM at the time was an ardent opponent of the New Deal, which bolstered labor unions and public transport, and admired and supported Adolf Hitler.[14] GM was compensated $32 million by the U.S. government because its German factories were bombed by U.S. forces during the war.[15]

IT&T[edit]

On August 3, 1933, Adolf Hitler received Sosthenes Behn (then the CEO of ITT) and his German representative, Henry Mann, in one of his first meetings with US businessmen.[16][17][18][need quotation to verify]

In his book Wall Street and the Rise of Hitler, Antony C. Sutton claims that ITT subsidiaries made cash payments to SS-leader Heinrich Himmler. ITT, through its subsidiary C. Lorenz AG, owned 25% of Focke-Wulf, the German aircraft-manufacturer, builder of some of the most successful Luftwaffe fighter-aircraft. In the 1960s, ITT Corporation won $27 million in compensation for damage inflicted on its share of the Focke-Wulf plant by Allied bombing during World War II.[16] In addition, Sutton's book uncovers that ITT owned shares of Signalbau AG, Dr. Erich F. Huth (Signalbau Huth), which produced for the German Wehrmacht radar equipment and transceivers in Berlin, Hanover (later Telefunken factory), and other places. While ITT - Focke-Wulf planes were bombing Allied ships and ITT lines were passing information to German submarines, ITT direction-finders were saving other ships from torpedoes.[19] The payments to Himmler were noted in a 1946 banking investigation report by the Office of Military Government, United States.[20]

In 1943, ITT became the largest shareholder of Focke-Wulf Flugzeugbau GmbH with 29%, and remained so for the duration of the war. This was due to Kaffee HAG's share falling to 27% after the death in May of Kaffee HAG chief Dr. Ludwig Roselius. OMGUS documents reveal that the role of the HAG conglomerate could not be determined during WWII.[21]Eastman-Kodak[edit]

Kodak's European subsidiaries continued to operate during the war. Kodak AG, the German subsidiary, was transferred to two trustees in 1941 to allow the company to continue operating in the event of war between Germany and the United States. The company produced film, fuses, triggers, detonators, and other materiel. Slave labor was employed at Kodak AG's Stuttgart and Berlin-Kopenick plants.[22] During the German occupation of France, Kodak-Pathé facilities in Severan and Vincennes were also used to support the German war effort.[23] Kodak continued to import goods to the United States purchased from Nazi Germany through neutral nations such as Switzerland. This practice was criticized by many American diplomats, but defended by others as more beneficial to the American war effort than detrimental. Kodak received no penalties during or after the war for collaboration.[22]

British, Swiss, US, Argentinian and Canadian banks[edit]

German financial operations worldwide were facilitated by banks such as the Bank for International Settlements, Chase and Morgan, and Union Banking Corporation.[13]Brown Brothers Harriman & Co. acted for German tycoon Fritz Thyssen, who helped finance Hitler's rise to power.[24]

"Switzerland laundered hundreds of millions of dollars in stolen assets, including gold taken from the central banks of German-occupied Europe," according to PBS. Switzerland resisted returning these funds, and the Washington Agreement of 1946 merely required the resitution of 12% of the stolen gold.[25]

A forgotten document discovered in a Buenos Aires bank in the 1980s listed more than 12,000 accounts with Nazi ties, drawn up in 1938 after an investigation initiated by an anti-fascist government. The list shows transfers to an account at Schweizerische Kreditanstalt (SKA), ancestor of Crédit Suisse. The account had which had ties to the Bank der Deutschen Arbeitsfront, controlled by the Nazis.[26]

In March 1939 the Bank of England surrendered to Germany 5.6 million pounds worth of gold that belonged to the National Bank of Czechoslovakia, six months before England entered World War II.[27] "The documents released by the Bank of England are revealing, both for what they show and what they omit. They are a window into a world of fearful deference to authority, the primacy of procedure over morality, a world where, for the bankers, the most important thing is to keep the channels of international finance open, no matter what the human cost."[27]

Both the Bank of Canada and the US Federal Reserve Bank helped to launder Nazi gold by transferring it from a Swiss account to one held by neutral Portugal. A single transaction in June 1942 by the Canadian bank moved 4.02 metric tons of gold.[28]

Hollywood[edit]

Major Hollywood studios have also been accused of collaboration, in making or adjusting films to Nazi tastes prior to the U.S. entry into the war.[1] Universal Pictures edited All Quiet on the Western Front to remove scenes that had sparked outcry in Germany.[29] Georg Gyssling, the German consul in Los Angeles in 1933, threatened the American film studios with a German film regulation known as "Article 15": A company that distributed an anti-German picture anywhere in the world could see all its movies banned in Germany, a large market for American cinema.[29] He was unable to use this tactic against The Mad Dog of Europe, produced by an independent company that did not do business in Germany, but successfully prevented it from being made by telling the Motion Picture Producers and Distributors Association of America that if the movie were made, the Nazis might ban all American movies from Germany.[29][30]

Other[edit]

Robert A. Rosenbaum writes: "American companies had every reason to know that the Nazi regime was using IG Farben and other cartels as weapons of economic warfare"; and he noted that

"as the US entered the war, it found that some technologies or resources could not be procured, because they were forfeited by American companies as part of business deals with their German counterparts."[31]

The Associated Press (AP) supplied images for a propaganda book titled The Jews in the USA, and another titled The Subhuman.[35] The news agency reached a formal agreement with the Nazi regime, hiring Nazi propagandists as reporters.[36] For example when the Germans discovered mass killings by the Soviets after entering Lviv, SS propagandist Frank Roth sent AP photos of those bodies, but refrained when the Nazis carried out a pogrom against Jews.[36]

Spain and Portugal sold tungsten to Germany, which needed it to refine iron ore into steel for tanks and bombers; it also bought oil from Romania, chromium from Turkey and ball bearings from Sweden.[37][38]

Swiss companies including Oerlikon-Bührle, Tavaro, Hispano-Suiza and Dixi sold the Nazis antiaircraft guns, cannon, military precision instruments and ammunition.[39]

After the war, some of those companies reabsorbed their temporarily detached German subsidiaries, and even received compensation for war damages from the Allied governments.[13]

See also[edit]

- Charles Bedaux

- Hugo Boss

- Swedish iron-ore industry during World War II

- Black market in wartime France

- Carlingue

- Forced labour under German rule during World War II

- German American Bund

- Joseph Joanovici

- Henri Lafont

- IBM and World War II

- IBM and the Holocaust

- It Can't Happen Here

- List of companies involved in the Holocaust

- Nazi Billionaires

- Pierre Bonny

- The Collaboration: Hollywood's Pact with Hitler

References[edit]

- ^ a b Schuessler, Jennifer (25 June 2013). "Scholar Asserts That Hollywood Avidly Aided Nazis". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on 3 February 2018. Retrieved 20 March 2018.

- ^ English, Simon (2003-11-03). "Ford 'used slave labour' in Nazi German plants". The Daily Telegraph. ISSN 0307-1235. Archived from the original on 2018-03-20. Retrieved 2018-03-20.

- ^ Edmund N. Todd (June 2016). The Politics of Industrial Collaboration during World War II: Ford France, Vichy and Nazi Germany by Talbot Imlay and Martin Horn (review). Vol. 17. Enterprise & Society, Cambridge University Press. pp. 434–435. Archived from the original on 2022-05-06. Retrieved 2023-10-05.

- ^ "Mark Thomas discovers Coca-Cola's Nazi links". New Statesman. Archived from the original on 20 March 2018. Retrieved 20 March 2018.

- ^ "Coca-Cola collaborated with the Nazis in the 1930s, and Fanta is the proof". Timeline. 2 August 2017. Archived from the original on 19 August 2018. Retrieved 20 March 2018.

- ^ Black, Edwin (27 February 2012). "IBM's Role in the Holocaust – What the New Documents Reveal". HuffPost. Archived from the original on 29 October 2017. Retrieved 20 March 2018.

- ^ Black, Edwin. "How IBM Technology Jump Started the Holocaust". Gizmodo. Archived from the original on 21 March 2018. Retrieved 21 March 2018.

- ^ Black, Edwin (19 May 2002). "The business of making the trains to Auschwitz run on time". San Francisco Chronicle. Archived from the original on 28 March 2018. Retrieved 28 March 2018.

- ^ a b c d Ford and GM Scrutinized for Alleged Nazi Collaboration Archived 2019-10-28 at the Wayback Machine, Michael Dobbs, Washington Post, November 30, 1998; Page A01

- ^ Black, Edwin (2008). IBM and the Holocaust: The Strategic Alliance Between Nazi Germany and America's Most Powerful Corporation. Dialog Press. ISBN 9780914153108.

- ^ Pauwels, Jacques R. (2017). Big Business and Hitler (in German). James Lorimer & Company. ISBN 978-1-4594-0987-3.

- ^ Allen, Michael (2002-01-01). ""Stranger than Science Fiction: Edwin Black, IBM, and the Holocaust."". Johns Hopkins University Press. 43 (1): 150–154. JSTOR 25147861. Archived from the original on 2023-03-08. Retrieved 2022-03-07.

- ^ a b c d Stone & Kuznick 2013, p. 82.

- ^ Black, Edwin (December 6, 2006). "Hitler's carmaker". The Jerusalem Post. Archived from the original on June 21, 2023. Retrieved July 31, 2023.

- ^ Dobbs, Michael (November 30, 1998). "Ford and GM Scrutinized for Alleged Nazi Collaboration". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on October 28, 2019. Retrieved July 31, 2023.

- ^ a b Sampson, Anthony. The Sovereign State of ITT, Hodder and Stoughton, 1973. ISBN 0-340-17195-2

- ^ AMERICAN VISITS HITLER. Behn of National City Bank Confers With Chancellor in Alps. New York Times, 1933-08-04, "AMERICAN VISITS HITLER.; Behn of National City Bank Con- fers With Chancellor in Alps". The New York Times. 1933-08-04. Archived from the original on 2014-03-07. Retrieved 2013-05-16.

- ^ »Empfänge beim Reichskanzler«, Vossische Zeitung, Berlin 1933-08-04, Abendausgabe, Seite 3, "Vossische Zeitung Berlin 1933-08-04". Archived from the original on 2014-03-07. Retrieved 2013-05-03.

- ^ The Office of Military Government US Zone in Post-war Germany 1946-1949, declassified per Executive Order 12958, Section 3.5 NND Project Number: NND 775057 by: NND Date: 1977

- ^ Adams, Foster; Lang, Emil (March 1, 1946). "OMGUS, Finance Division, Bank Investigation Report: Baron Kurt von Schroeder". National Archives Catalog. Retrieved March 7, 2024.

- ^ Leidig, Ludwig. Bombshell. sbpra, 2013 ISBN 978-1-62516-346-2

- ^ a b Friedman, John S. (March 8, 2001). "Kodak's Nazi Connections". The Nation. Archived from the original on April 10, 2021. Retrieved January 14, 2023.

- ^ Collins, p. 255

- ^ Campbell, Duncan (25 September 2004). "How Bush's grandfather helped Hitler's rise to power". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 15 March 2018. Retrieved 20 March 2018.

- ^ The Role of Swiss Financial Institutions in the Plunder of European Jewry Archived 2021-02-16 at the Wayback Machine, Institute of the World Jewish Congress, Frontline, PBS, 1996

- ^ Financement des nazis avant-guerre : l'incroyable liste argentine Archived 2023-03-21 at the Wayback Machine, Éric Chaverou, Camille Magnard, Radio-France, 8 March 2020

- ^ a b How bankers helped the Nazis Archived 2023-08-29 at the Wayback Machine, Adam LeBor, Sydney Morning Herald, August 1, 2013

- ^ Paper Trail of Nazi Gold Leads To US and Canadian Banks: Jewish leaders find records of transactions between Switzerland and Portugal assisted by N. Americans Archived 2023-08-29 at the Wayback Machine. Mark Clayton, Christian Science Monitor. July 18, 1997

- ^ a b c Ben Urwand (July 31, 2013). "The Chilling History of How Hollywood Helped Hitler (Exclusive): In devastating detail, an excerpt from a controversial new book reveals how the big studios, desperate to protect German business, let Nazis censor scripts, remove credits from Jews, get movies stopped and even force one MGM executive to divorce his Jewish wife". Hollywood Reporter. Archived from the original on August 31, 2023. Retrieved October 5, 2023.

- ^ Red Carpet: Hollywood, China, and the Battle for Global Supremacy. Erich Schwartzel. 2022. ISBN 9781984879004

- ^ Robert A. Rosenbaum (2010). Waking to Danger: Americans and Nazi Germany, 1933–1941. ABC-CLIO. pp. 121–. ISBN 978-0313385032. Archived from the original on 2023-10-05. Retrieved 2023-05-31.

- ^ "History of the synthetic rubber industry". ICIS Explore. 2008-05-12. Retrieved 2021-01-29.

- ^ Obrecht, Werner; Lambert, Jean-Pierre; Happ, Michael; Oppenheimer-Stix, Christiane; Dunn, John; Krüger, Ralf (2011). "Rubber, 4. Emulsion Rubbers". Ullmann's Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry. Weinheim: Wiley-VCH. doi:10.1002/14356007.o23_o01. ISBN 978-3527306732.

- ^ John F. Ptak (23 September 2008). "Distinguishing Oświęcim (town), Auschwitz I, II, & III, and the Buna Werke". From the "Pamphlet Collection" of the Library of Congress. Ptak Science Books. Retrieved 18 July 2014.

- ^ "What the AP's Collaboration With the Nazis Should Teach Us About Reporting the News". Tablet Magazine. Archived from the original on 20 March 2018. Retrieved 20 March 2018.

- ^ a b Revealed: how Associated Press cooperated with the Nazis: German historian shows how news agency retained access in 1930s by promising not to undermine strength of Hitler regime Archived 2023-08-23 at the Wayback Machine, Philip Oltermann, The Guardian 30 Mar 2016.

- ^ History's Biggest Robbery: How the Nazis Stole europe's Gold Archived 2023-08-29 at the Wayback Machine, Wharton School, University of Pennsylvania, December 16. 2014

- ^ Neutral Nations Kept Nazi Forces Going, U.S. Says Archived 2023-08-29 at the Wayback Machine, Norman Kempster, Los Angeles Times, June 3, 1998

- ^ New Records Show the Swiss Sold Arms Worth Millions to Nazis Archived 2023-08-29 at the Wayback Machine, Alan Cowell, New York Times, May 29, 1997

Sources[edit]

- Stone, Oliver; Kuznick, Peter (2013). The Untold History of the United States. Simon and Schuster. ISBN 978-1-4516-1352-0.

Further reading[edit]

- Aalders, Gerard; Wiebes, Cees (August 1, 1996). The Art of Cloaking Ownership: The Secret Collaboration and Protection of the German War Industry by the Neutrals : the Case of Sweden. Amsterdam University Press. ISBN 978-90-5356-179-9.

- Bera, Matt (January 1, 2016). Lobbying Hitler: Industrial Associations between Democracy and Dictatorship. Berghahn Books. ISBN 978-1-78533-066-7.

- Billstein, Reinhold (August 1, 2004). Working for the Enemy: Ford, General Motors, and Forced Labor in Germany During the Second World War. Berghahn Books. ISBN 978-1-84545-013-7.

- Bitunjac, Martina; Schoeps, Julius H. (June 21, 2021). Complicated Complicity: European Collaboration with Nazi Germany during World War II. Walter de Gruyter GmbH & Co KG. ISBN 978-3-11-067118-6.

- Bowen, Wayne H. (August 1, 2000). Spaniards and Nazi Germany: Collaboration in the New Order. University of Missouri Press. ISBN 978-0-8262-6282-0.

- Christianson, Scott (2010). The Last Gasp: The Rise and Fall of the American Gas Chamber. Berkeley: University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-25562-3.

- Darcy, Shane (August 1, 2019). To Serve the Enemy: Informers, Collaborators, and the Laws of Armed Conflict. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-878889-8.

- Doherty, Thomas (April 2, 2013). Hollywood and Hitler, 1933–1939. Columbia University Press. ISBN 978-0-231-53514-4.

- Drapac, Vesna; Pritchard, Gareth (September 16, 2017). "Resistance and Collaboration in Hitler's Empire". Bloomsbury Publishing.

- Forbes, Neil (August 1, 2000). Doing Business with the Nazis: Britain's Economic and Financial Relations with Germany, 1931–1939. Psychology Press.

- Frøland, Hans Otto; Ingulstad, Mats; Scherner, Jonas (October 19, 2017) [22 September 2016:Springer]. Industrial Collaboration in Nazi-Occupied Europe: Norway in Context. Palgrave Macmillan UK.

- Hart, Bradley W. (October 2, 2018). Hitler's American Friends: The Third Reich's Supporters in the United States. St. Martin's Publishing Group.

- Imlay, Talbot C.; Horn, Martin. The Politics of Industrial Collaboration during World War II.

- Lund, Joachim (August 1, 2006). Working for the New Order: European Business Under German Domination, 1939–1945. Copenhagen Business School Press DK. ISBN 978-87-630-0186-1.

- Urwand, Ben (September 10, 2013). The Collaboration: Hollywood's Pact with Hitler. Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-72835-6.