Azerbaijani calendar beliefs

Azerbaijani calendar beliefs are common beliefs about the naming of different times (cosmic periods, years, months, etc.) in Azerbaijani culture.

The formation of the Azerbaijani folk calendar is based on the attitude to nature, the movement of celestial bodies, and agricultural traditions. The transition from winter to spring occurs when the world sleeps, and is celebrated with Novruz holiday. Although Nowruz and Khidir Nabi holidays are celebrated together in different regions of Azerbaijan, the good celebration of one of the holidays is observed with the poor celebration of the other. Chilla night is celebrated on the occasion of the beginning of winter, Sadda holiday is celebrated on the occasion of the transition from Big Chilla to Little Chilla.

In the dialects of the Azerbaijani language, weekdays are referred to as salt, grief, honey, milk days, etc. On the day of ancestors, known as the Name Day, the deceased are remembered, and as a remnant of Shamanism, porridge is consumed.

Cosmic cycles[edit]

Ivar Lassi, who studied the traditions of Muharram in Azerbaijan, reported that Azerbaijanis believe in the existence of 10 cosmic cycles, each lasting 10,000 years.[1] These cosmic cycles are divided into 12-year solar years. Azerbaijanis believed that the 5th cycle continued into the 1910s.

History of calendars in Azerbaijan[edit]

Jalali calendar[edit]

The absence of an exact date of Khizir Nabi holiday, but the celebration of Nowruz holiday on a specific day, is explained by the fact that Nowruz holiday Nowruz was officially incorporated into the Jalali calendar in the 11th century.[2]

The Twelve Animal Calendar[edit]

Georgian sources show more of an Eastern (Uyghur-Chagatai) character, and it is possible to encounter the Twelve Animal Calendar dating back to the Mongol period. The term "Siçan ili" used is of Oghuz origin (the word "il" is more precisely of Azerbaijani origin). Certainly, these Oghuz elements should be attributed to local Eastern Ottoman-Azerbaijani influences. In the same way, the word "ilan" used for the year is either of Azerbaijani or Turkish origin.[3]

According to Turkish historian Osman Turan, the calendar with twelve animals still exists in Azerbaijan.[4] In general, the Turkish calendar played an important role in the lives of all Turkic peoples of the Caucasus and was passed on to other peoples in the neighborhood.[5]

The commonly used names are as follows: mouse, ox-cow, tiger, rabbit, dragon (or crocodile and fish[6]), snake, horse, sheep (or goat), monkey, chicken-rooster (or simply bird), dog, pig. Such naming of years is considered "Tarikh-i Turki".[7]

In Azerbaijani folklore, beliefs related to the Turkic calendar are encountered.[8][9] According to a widespread belief among the people, the nature of the upcoming year, whether it will be good or bad, is associated with the character and traits of the animal named after it. For example, when the year of the snake arrives, they say that the weather will be warm, drought will pass, and relations will not be normal. In the year of the rabbit, the harvest is plentiful, in the year of the dragon (crocodile), there is a lot of rain, in the year of the pig, the weather will be harsh, etc.[10]

According to another calendar myth, fortune tellers who gathered in one place on Novruz gave names to the years, and if the year is based on an animal, people will show the character of that animal. For example, people gnaw and destroy in the year of the mouse, be tolerant in the year of the horse, and fight in the year of the dog. Another myth tells the story that because people confused the years, their rulers named the years after the animals that appeared in front of them.[11]

Turkish calendar[edit]

In the theoretically existing Turkish calendar (based on lunar years), the 1st month is called Aram, and the last month is called Haqqsabat. The remaining months are named by numbers. An intercalary month is added after the 2nd or 3rd year. This month is called Sivan, which means "crying".[12]

Azerbaijan folk calendar[edit]

In the Azerbaijani folk calendar, different times (months, periods, holidays or ceremonies) are marked with special names. The formation of the folk calendar in Azerbaijan is rooted in the attitude to nature, celestial movements and agricultural traditions. In the folk calendar, terms such as the month of plowing, the month of migration, the month of vay nene, the month of irrigation, and the month of harvest are used.[13]

According to legend, in ancient times, when the year was divided into months, each month was given 32 days, except for the "Boz" month, which had 14 days. E very month gives 1 day to the Boz month so that the Boz month does not get hurt. Some months give him days again because the Boz month is still short. However, since the Boz month takes days from other months, its days are not similar in terms of weather conditions.[13]

Historically, in places where Nowruz holiday is celebrated with great enthusiasm in Azerbaijan, Khidir Nabi holiday has either not been celebrated or has been poorly celebrated. At the same time, where Khidir Nabi holiday is well celebrated, Nowruz holiday has not been celebrated in an important way. Khidir Nabi holiday is not celebrated in the southern region of the Republic of Azerbaijan and in the plains of the Shirvan area.[2]

Spring[edit]

- When the universe sleeps. It is a mysterious time that marks the end of winter and the beginning of spring. It occurs at the moment when the last Tuesday of the year or the night before the Nowruz holiday is transformed into daylight. Rivers, streams, that is, running water, stop for a moment, and then they start flowing again.[14]

- Nowruz (March 21).The New Year, the arrival of Spring, the awakening of nature, and the beginning of summer agricultural activities.[15]

- Baca-baca day. It is the first day of Nowruz.[16]

- Chershenbe sur. It is the first Tuesday after the spring equinox. According to information provided by Adam Olearius, Iranians (meaning Turks in the given example) consider this day unlucky. They refrain from work and the markets are closed.[17]

- Garayaz (oğlaqqıran, goat-breaker). This period, from the end of April until late spring, about forty days after the beginning of summer, is called "Garayaz" in the folk calendar.[15][18]

- Goygavan/Goygovan. It is used in Babek, Shahbuz and Julfa. It is the period when cattle come out of winter. "Goyqavan" means "searching for sky grass, fleeing when the sky falls, and eating the sky."[19]

- Hefteseyri. In the past, Shirvan used to celebrate the festival of flowers, which was called the Hefteseyri. This holiday begins in Nowruz and was celebrated every Friday for 30–40 days. In the north-west of Azerbaijan, this holiday was celebrated under the name "Rose festival".

- Sun rituals. If the 3rd and 4th days after Novruz are rainy, people make a doll and sing songs calling for the Sun.[15]

- Planting month. Spring is the most productive period of a farmer's life.[15]

- Rain month. This is the name of the first month of the spring season, it comes from the words Nisan and Neysan (April).[15]

- Nature day. Iranian Azerbaijanis visit nature on the thirteenth day of the new year and celebrate until the evening.[20]

- Suceddim. It is a tradition to swim in the spring. It is spread in many parts of Azerbaijan and among the Azerbaijanis of Armenia.[21]

- Green light month. In the mountains and foothills, the month of April is called this.[15]

- Garıborcu. It refers to the period until April 15. They sing songs about the change from winter to spring, called "The Change of Garı with March". In Ordubad and Shahbuz, the period until April 15, when the weather is cold, is called karnaburt.[15][22][19]

- Terchıkh period. It is the period when new summer grasses grow, and sheep and goats are sheared at night.[15]

- Kotan (cut) period. It is the period when plowing works are started. They are celebrating the Shum Festival, wishing them a prosperous year ahead.[15]

- Cut and Kotan holiday. It is held in cüt or kotan time. Lavash or tandir is placed around the neck of the oxen, and the animals are roamed in the field.[15]

- Sprout (or grass) month. It is the period when gardens are cultivated.[15]

- Rose age. They celebrated the rose water festival, everyone gave each other rose water in small perfume bottles, and had fun with various singing and ritual games.[15]

- Grass cutting period. It is held in some regions at the end of the spring season.[15]

Summer[edit]

- Harvest time. It's early summer.[15]

- Susepen holiday. Celebrated in the Ordubad region with the arrival of summer. It involves welcoming the sun and sacrificing an animal.[23]

- Cırhacır period (or dragonfly period). It is the middle month of summer, the reason for the appearance of this name is that due to the intensity of the scorching heat falling from the sky and the drought, dragonflies start to chirp in the lowlands.[15]

- Abrizagan holiday. Ceremonies related to water were performed on the holiday. With various water containers in their hands and accompanied by music, everyone would gather at the riverside, near a spring, orany water source and play, throw water on each other, and try to push each other into the water.[15]

- Goradoyan month. A period of the middle month of summer is called. er. During this time, grape clusters slowly start to ripen. Women collect these goras, wash them, pour them into large wooden plates, beat a round river stone with a hammer and extract the water, making abgora (gora water).[15]

- Gorabishiren month. It takes from Goradoyen to the middle of August. It is the hottest period of summer, when the grapes swell and turn dark.[15]

- The period of migration from the highlands. The Elat holiday is celebrated on July 26, when Azerbaijani nomads return from the mountains to the plains in Armudlu village of Dmanisi in Georgia. At this time, tents are erected, horse races are held, and bread is prepared. In the summer season, beekeepers also go to the plain. Because special flowers grow above, in cool places.[24]

- Guyrugdogdu (tail-born or tail-frozen). It is called the second period of summer. It is determined by the appearance of comet-like stars extending from the eastern horizon towards the west just before dawn, and agricultural activities are performed during this period. As early as 1905, Hasan Bey Zardabi wrote in his article "Quyruq doğdu, çillə çıxdı": "If anyone wakes up early in the morning on July 25 (August 7 according to the new calendar) and looks at the sunrise, he will see a group of stars resembling that tail. The time of quyruqdoğdu is from August 6th to 15th. From that period onwards, the weather gradually cools down"[15]

- Honey moon. The beginning of honey harvesting brings joy to beekeepers. On this occasion, they rejoice, give each other a smile, put honey on their cheeks, and wish for blessings.[15]

- Elgovan (or the days of breaking burku). It is the last month of summer. During this period, the mist often falls, there is no shortage of fog and drizzle from the mountains. A cold wind blows from early in the morning.[15]

- Sonay. It is called the last moonlit nights of summer. In the Sonay nights, they make the sound of AVAVA by tapping hands at their mouths, as a call for gathering. Then they gather and play late the moonlight nights. Of the necessarily played games/plays are: Mallaharay and “Bənövşə Bəndə Düşə”.[15]

- Fig ripening period. In Absheron, the end of August and the beginning of September are called so.[15]

Autumn[edit]

- Equality of night and day (Paghtigan). In Azerbaijani folk belief, the Moon and the Sun are depicted as lovers. Their love is eternal, but they can never be united, but they can see each other's faces at the equinox. Despite this, they still lose each other without being able to meet. In Azerbaijani villages, various games are played on this night.[25]

- Gochgarishan. Among the elite population of Azerbaijan, the beginning of autumn is called Gochgarishan. During this month, sheep that have been previously bred are released into the herd, taking into account that breeding coincides with the last month of winter (boz ay). Sheep are released into the herd within the first 5–10 days of autumn. This period experiences cooler weather, heavy rainfall, and strong winds.[15]

- Shanider. It is a celebration and thanksgiving ceremony held by picking grapes and baking doshab.[15]

- Harvest season. The first apple picked before dawn and before the sunrise of the first day of this season grants Eternal Life to the person.[26]

- Mehregan holiday. It was held on the occasion of harvest. Until recent years, this holiday was celebrated as the labor victory of the year, the final holiday of the year - the harvest holiday.[27]

- Khazal month or the girovdushen moon. It's November. Passes with rain and lightning.[15]

- Pomegranate holiday. The festival features a fair and an exhibition that displays different local varieties of pomegranates as well as various pomegranate products produced by local enterprises. During the festival, music and dance performances are presented each year. The festival also includes athletic performances and various craftsmen, potters, millers, blacksmiths, artists, performances of folklore groups and paintings.[29]

- "Kovsec" ceremony was performed in girovdushan month. A person dressed in a ridiculous costume, with a laughing face, would parade through the village, declaring to the crowd that he is the enemy of winter. People in the surrounding area sprinkled water on him, threw snow, and played funny games and entertainments around him. He was holding a crow with his feathers in one hand and a fan in the other hand and waving it, saying "it's hot, it's hot, I don't care" over and over.[15]

- Autumn period or leaf shedding time. During this period, a windy breeze called Khezan wind would blow, causing the yellow leaves remaining on the trees to fall, marking the beginning of the leaf-falling season.[15]

- Nakhirgovan (or oglaggiran). The wind blowing in the last month of autumn first of all drove the cattle grazing outside into the barn. After that, the cold sets in.[15]

- The time of transitioning from autumn to winter. t the end of autumn, the slopes of the mountains are covered with smoke. In a moment, hail pours, rain falls, snow is mixed and blown in such a way that the eye cannot see.[15]

Winter[edit]

- Big Chelle. It is the first stage of winter, lasting 40 days. Shab-e Chelleh is the night opening the "big Chelleh" period, that is the night between the last day of autumn and the first day of winter.[15]

- Chelle night. Countless bonfires were lit to mark the beginning of winter. Fireworks were set off everywhere, people gathered together to celebrate, played interesting games and plays, made sacrifices, played music.[15]

- The ninth day of winter. On that day, after midnight, a childless woman who eats a frosted apple will have a child.[15]

- Karagish. These are the snowy, stormy, freezing days of the Great Chelle. During this time, winter passes heavily and sadly, with snow mixed with wind howling.[15]

- Little Chelle (February 1–20). It is the second stage of winter. Generally, Little Chelle is distinguished by its severe, icy cold. That's why this period is also called the boyhood of winter, the zalo-zalo time of winter, the harsh time of winter.[15]

- Sadda holiday. It is a holiday celebrated 50 days before Nowruz. Sadda holiday is a holiday that shows people's attitude towards winter and demonstrating that they are not afraid of winter.[15]

- Time of Yalguzag. It is called the first 10 days of Little Chelle. It is also called "Khidir Nabi days". These ridge-cold times are associated with Khidir Nabi and it is said that "Khidir comes, winter comes; Khidir leaves, winter leaves"[30]

- Khidir Nabi holiday. It is a seasonal holiday celebrated in honor of Khidir Nabi, who is associated with the cult of greenery and water. Khidir is a protector who rides a gray horse. As Khidir is believed to be a healer, some ritual practices as regards to health issues can be seen on Hıdırellez Day. On that day, meals cooked by lamb meat are traditionally feasted. It is believed that on Khidirellez Day all kinds or species of the living, plants and trees revive in a new cycle of life, therefore the meat of the lambs grazing on the land which Khidir walks through is assumed as the source of health and happiness. In addition to these, some special meals besides lamb meat are cooked on that day.[15][31]

- Thursdays of Little Chelle. These are the dates when nature starts to come alive. These three Tuesdays are called "thief's tuesday", "thief's bugh", "thief's usku". Although there is no awakening like in the Thursdays of the Boz Month (Wind, Fire, Water, Earth), warmth goes to the ground. People believe that they will be protected from evil forces by burning the flakes and carring them around the house 3 times.[32]

- Boz Month (or chellebeces, alachalpov, gray chelle, ala chelle, crying-smiling month, fetus month). It is the last stage of winter, lasting 30 days. During this period, due to frequent weather changes and the high number of gloomy, sunless days, it is called the gray, gloomy, and dark period in the folk calendar.

- Tuesdays of the Boz month. They are the four Tuesdays before Novruz, related to the four elements (Wind, Fire, Water, Earth).[32]

- Kos-kosa game. This game humorously depicts the death of winter and the beginning of spring. Neighborhood children play this game in front of houses, collecting money and food. The face of "Kosan" (the mask) symbolizes devotion to the spirit of nature, and wearing fur inside out also has a sacred meaning.[33]

- Vasfi-hal. Various items (rings, earrings, banners, ornaments) are placed inside a wishing bowl, and after reciting a ceremonial song, one of them is secretly chosen. The fate of the item depends on the intention of its owner.[34]

- Danatma time.It is the ceremony of the sunrise and welcoming on the last Tuesday. Girls fill a bowl with water, cover it with a cloth, and put jewels in the water.[35]

- When the universe sleeps. It is a mysterious time that marks the end of winter and the beginning of spring. It takes place on the last Tuesday of the year or at the moment when the night turns into day, which will open Nowruz. Streams and rivers, that is, flowing waters, stop for a moment, then start flowing again.[33]

Other[edit]

In Iranian Azerbaijan, ceremonies and festivities are held under the names of Mountain Migration, Shepherd's Festival, Lamb Day, Shepherd's Day, Grass Migration, and Sheep Day.

- Lamb day. It was performed after the first birth in the sheep herd. Shepherds used to dance and sing, and competitions were held.

- Ram day. It was held ten days before moving to the highlands. The head shepherd or village elder would give advice to the youth. The sheep were decorated with various colored wool and bells were hung around their necks.

- Grass migration. It was held on the occasion of the end of agricultural work and village work. During this traditional temporary migration, the elderly, children, and livestock were taken to the summer pasture.

Days of the week[edit]

| Day | Names |

|---|---|

| I day | The day of salt, the day of the prophet, banamiya, banuma |

| II day | The day of mourning, "Khas day", the day of the qele |

| III day | Milk day, harbe |

| IV day | Adina day |

| V day | Adina day |

| VI day | The day after Adina |

| VII day | Milk day or Azat day |

In the dialects of the Azerbaijani language, the following expressions are used for the days of the week:

- Salt day (I day). The first day in Goychay was named after the lexeme "prophet". In Baku, the first day is called banuma day, and in Ordubad and Shahbuz, it is called banamiya.

- Day of mourning or i.e. special day (II day). In Agbaba, Khanlar, Gakh, Gazakh, Mingachevir, Sheki dialects, it is known as "khas day" (special day).[36]

- Ad(ina) day (IV day). It is used as the fourth day in Ganja, Gazakh, Lankaran, Sheki, Shamkir, Zangilan. In Ganja, the donation given on the fourth day for a person who dies is called adnaliq (adnalikh). This day is called "ata-baba day" (father's day) in some parts of Azerbaijan, as it is associated with spirits.[37] On the day of the adina, special food is cooked in houses and graves are visited, the dead are remembered. One of the remains of the shamanism customs that were influenced by Islam in Azerbaijan is the ash that Azerbaijanis eat on Thursdays in honor of the spirits of the dead.[38][39]

- Adina day (V day). It is used as the fifth day in Gadabay and Tovuz.[38]

- The day after Adina (VI day). It is used as Saturday in Gadabay.[38]

- Milk day or Azat day (VII day). The name of milk day was used in Baku governorate. In Gədəbəy and Tovuz dialects, it is referred to as "xas günü" (special day).[40]

The days of milk and salt are thought to be related to the Moon and the Sun. The expressions "clear as milk", "pure as milk" are still used today. In naming the second day as the "day of mourning", "gam day", similarities have been observed in the language of Eastern European, Caucasian, Front Asian and Balkan Turks, as well as in some Finnish peoples of Eastern Europe.[16] Under the influence of Islam, week names of Turkic origin have been replaced by names of Arabic-Persian origin or used together with them. IIn modern times, the poet I. Tapdıq introduced the names Gunbir (Day one), Guniki (Day two), Gunuch (Day three), Gundord (Day four), Gunbesh (Day five), Gunalti (Day six) to help children better memorize the week days.[41]

Examples of the day of the week in dialects[edit]

In Baku dialect, danna used in Goychay, Mingachevir, Megri dialects, dannari in Goychay dialects means "morning". The expression "danna of the milk day" used for the second day means "the morning of the milk day". In Mahmud Kashgarli's "Dictionary", tang is used in the sense of "morning, at dawn".[42]

| Days of the week | Baku dialect[42] | Tabriz dialect[42] | Derbent dialect[42] | Yardimli dialect[43] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1st day | Milk day | Gichik hacilar | Aghir day | |

| 2nd day | Danna of Milk day | Nes/khas | Gele day | |

| 3rd day | Danna of Danna | Milk day/odd day | Kharbe | |

| 4th day | Day for cooking yoghurt rice | Salt day | Etine | |

| 5th day | Day of little fall to milk | Evening of Etine | ||

| 6th day | Day when the tribe moves all here | Shenbe | ||

| 7th day | Milk day has come again | Boyug hacilar |

Days of the week in folklore[edit]

In Azerbaijani religious tales, the days of the week are separated according to whether they are useful, successful or unprofitable. Although the perceptions about the days of the week are formed on Islamic values, they also have a nature associated with superstition. Friday is one of the sacred days in Islam. The connection between the creation of Prophet Adam, his entry into heaven, his exit from heaven, and the day of judgment with Friday has led to its significant importance in Islamic history. In Islam, Friday is a day of communal worship in Islam. It is believed that sins are forgiven for those who listen to the sermon and perform prayers in the mosque on that day. In Azerbaijani religious tales, Friday is described as a holy day. Fairies come to bathe in the lake on Fridays. Thursday and Saturday are considered lucky days as they are the day before and after Friday. As a result of this, it is mentioned in the Azerbaijani tale that according to the words of the ancestors, those who go on a trip on Saturday will return early and the trip made on that day will be easier.[44]

Visiting times[edit]

- Stream. In the summer, mothers recite prayers in the form of poetry when bathing their children in these waters.[45]

- Aynali mountain. On the 13th day of summer (Nature Day), Iranian Azerbaijanis dance and celebrate on the slopes of this mountain.[45]

- Pir mountain. Before sowing or moving to summer pastures, the grave on Pir Mountain in the Kivi village of Maraga is visited by the locals and shepherds.

- Shahdag. The largest mountain in the northeastern part of Azerbaijan, is considered sacred by the people of the region. In the summer months, visits to Shahdag are organized, grave sites in the region are visited, pieces of cloth are tied to trees, and sacrifices are made.[46]

- Kirkhgiz hill. It is believed that stones cry every Friday on Kirkhgiz hill near Gobu and that day is an acceptable day for visits. This water is believed to be the tears of forty girls who turned into stones.[47]

Special times of the day and month[edit]

Times of the day[edit]

- Obashdan/before the dog falls off the hystack/The sun hasn't broken. It is early in the morning in Azerbaijani language dialects.[48]

- Twilight (early dawn) and alagaranlig (after sunset) times. These are the times when the star of Zohra appears in the sky, and it is considered suitable for embassies and wedding ceremonies. In this regard, there are beliefs such as "A child born at sunset spends his day abroad", "A child born at sunrise becomes a knight".[48][49]

- Gunerta/Midday, Afternoon. It is daytime in Azerbaijani language dialects.[48]

- Sher time/Dar time. This is in the evening and signifies the end of the day[48]

The times of the month[edit]

- New moon. Among the people, there are beliefs such as "who sees the moon when it rises will be successful", "who throws dirty water on the door where the moon shines will not receive good luck". When the new moon rises there are customs such as saying"blessed!" and reciting prayers, making wishes, and hanging a horn-shaped ornament on the door.[50]

- Ay bashi. Together with many Turkic peoples, Azerbaijanis also used this expression for the first day of the month.[50]

- 3 days of the month. At this time, a person who makes an intention and looks at the moon for 3 days will see the person he will marry in his dream.[51]

- 15 days of the month. It is believed that the child born at this time will be like a wrestler.[52]

In postage stamps[edit]

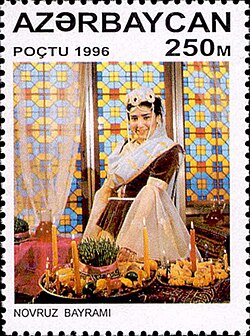

In Azerbaijan, various postage stamps have been issued related to the ongoing celebration of Nowruz holiday and Tuesdays, as well as the Chinese calendar.

-

Water Tuesday

-

Fire Tuesday

-

Wind Tuesday

-

Earth Tuesday

-

Nowruz holiday

-

Year of the Rooster. Chinese calendar

-

Year of the Dragon. Chinese calendar. Depicts Chinese characters and a Chinese dragon.

General overview[edit]

| Twelve-animal calendar | Azerbaijani folk calendar | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cosmic cycles | Years | Season | Month or period | Date | Minor periods | Date | Ceremonies in Azerbaijan | Date | Azerbaijani mythology | Days of the week |

| I | Mouse | Spring | Garayaz | 21 March-30 April | Time when the universe sleeps | 21 March |

|

Salt/ prophet/ banume day | ||

| II | Cow | Nowruz holiday | 21 March | Mourning/ khas / gele / nes day | ||||||

| III | Tiger | Chershenbe sur | 1th Teuesday | Danna of The danna/Milk day/Harbe | ||||||

| IV | Rabbit | Hefteseyri/Rose festival | 4th–6th Friday | Adina day (IV day) | ||||||

| V (1910s) | Dragon/ crocodile/ fish | Plowing month | Adina day (V day) | |||||||

| VI | Snake | Raining day | April | Nature day | 2 April | Day after Adina | ||||

| VII | Horse | Gariborcu | until 15 April | Milk, Azat day | ||||||

| VIII | Sheep | Terchikh period | ||||||||

| IX | Monkey | Kotan period | ||||||||

| X | Rooster | Cucerti month | ||||||||

| Dog | Rose age | Rose festival | ||||||||

| Pig | Grass mowing period | Last month of summer | ||||||||

| Summer | BHarvest time | Susepen holiday | 21 June | |||||||

| Circirama period | Abrizegan holiday | 17–18 July | ||||||||

| Goradoyen month | ||||||||||

| Gorabishiren month | until mid-August | |||||||||

| Guyrugdogdu | 6–15 August | Honey month | ||||||||

| Elgovan | Sonay | |||||||||

| Fig ripening period | ||||||||||

| Autumn | Gochgarishan | Pagta | ||||||||

| Shanider | ||||||||||

| Harvest season (Azerbaijan) | Mehregan holiday | |||||||||

| Girdushen | Pomegranate holiday | |||||||||

| Kovsec | ||||||||||

| Khezan time | ||||||||||

| Nakhirgovan | ||||||||||

| Winter | Big or Great Chelle | 21 December-29 January | Chelle nigh | 21 December | ||||||

| Garagish | ||||||||||

| Little Chelle | 29 January - 22 February | Sadda holiday | ||||||||

| Khizir Nabi days | Khizir Nabi holiday | 9–11 February | ||||||||

| Boz month | 22 February-22 March | Water Tuesday |

|

|||||||

| Fire Tuesday | ||||||||||

| Wind Tuesday | ||||||||||

| Earth Tuesday | ||||||||||

Sources[edit]

- Azərbaycan etnoqrafiyası, Üç cilddə (PDF) (in Azerbaijani). Vol. III. Baku: Şərq-Qərb. 2007. ISBN 978-9952-34-152-2.

- Abdulla, Bəhlul (2008). Novruz bayramı ensiklopediyası (PDF) (in Azerbaijani). Baku: Şərq-Qərb. p. 208.

- Acaloğlu, Arif; Bəydili, Celal, eds. (2005). Əsatirlər, əfsanə və rəvayətlər [Myths, legends and tales] (in Azerbaijani). Bahu: Șərq-Qərb.

- Albaliyev, Shakir Alif (2022). "The Ritual-Mythological Semantics of the Azerbaijan Khidir Nabi Holiday". Etnoantropološki Problemi / Issues in Ethnology and Anthropology. 17 (3). doi:10.21301/eap.v17i3.13.

- Axundov, A.A.; Kazımov, Q.Ş. (2007). Azərbaycan dilinin dialektoloji lüğəti (PDF). Şərq-Qərb. ISBN 978-9952-34-091-4.

- Əliyeva, Nuray (2018). Naxçıvan dialekt və şivələrinin etnoqrafik leksikası (in Azerbaijani). Nakhcivan: "Əcəmi" Nəşriyyat Poliqrafiya Birliyi.

- Rona-Tas, A. (1976). "A Volga Bulgarian Inscription from 1307". Acta Orientalia Academiae Scientiarum Hungaricae. 30 (2).

- Togan, Zeki Velidi (1981). Ümumi türk tarihine giriş (in Turkish). Vol. I. Istanbul: Enderun Kitabevi.

- Khudaverdiyeva, Tehrana (2023). "ON CHARACTERISTICS OF EPIC TIME IN MAGICAL AND RELIGIOUS TALES". Reviews of Modern Science: 183–184. doi:10.5281/zenodo.10032051.

- Oymak, İskender (2010). "ANADOLU'DA SU KÜLTÜNÜN iZLERi". Fırat Üniversitesi İlahiyat Fakültesi Dergisi. 15 (1): 0.

- Mahmud, Aynur (2018). "Sarıkız Efsanesi ve Azerbaycan Efsanelerinde Dağ ve Su Kültlerinin Sentezi". Uluslararası Kazdağları Sempozyumu Bildirileri.

- Caferoğlu, Ahmet (1956). "Azerbaycan ve Anadolu Folklorunda Saklanan İki Şaman Tanrısı". Ankara Üniversitesi İlahiyat Fakültesi Dergisi. 5 (1–4).

- Fərzəliyev, T. (1994). Azerbaycan Folkloru Antologiyası I. Nahcıvan Folkloru. Bakı: Sabah Nəşriyyatı.

- Lassy, I. (1916). The Muharram Mysteries among the Azerbaijan Turks of Caucasia. Helsingfors. pp. 214–225.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Najafov, A. (2019). Azerbaycan halk inanışları [Azerbaijani folk beliefs] (Unpublished master's thesis). Konya, Turkey: Necmettin Erbakan University, Institute of Social Sciences, Department of Philosophy and Religious Sciences.

- Abdullayeva, S. A. (2007). Azərbaycan folklorunda çalğı alətləri. Bakı: Adiloğlu. p. 216.

- Мамедли, А. (2017). Азербайджанцы. Москва: Наука. p. 708.

- Musalı, Namiq (2014). "Safevî Dönemi Tarih Yazımında On İki Hayvanlı Türk Takvimi" [Turkish Twelve-Year Animal Cycle Calendar in Historiography of Safavid Period]. I Türk Kültürü Araştırmaları Sempozyumu: 259–269.

- Floor, Willem; Javadi, Hasan (2013). "The Role of Azerbaijani Turkish in Safavid Iran". Iranian Studies. 46 (4): 10.

- Golden, Peter B. (1982). "The Twelve-Year Animal Cycle Calendar in Georgian Sources". Acta Orientalia Academiae Scientiarum Hungaricae. 36 (1/3): 197–206. JSTOR 23657850.

- Hacıyeva, Nərgiz (2021). "Türk dillərində həftə adları" [The names of the week in Turkish languages] (PDF). Teaching of Azerbaijani Languages and Literature (in Azerbaijani). 269 (3). Baku: AMEA Nəsimi adına Dilçilik İnstitutu: 112–126.

- Rahimi, M. (2019). "İran Türklüğünde Geleneksel Türk İnançlarının Etki ve İzleri". Milli Folklor. 16: 147–159. Archived from the original on 2023-08-19.

- Seyidov, M. A. (1996). "Eski Türk Kitabelerinde Yer-Sub Meselesi". A. Ü. D. T. C. F Tarih Araştırmaları Dergisi. 18 (29). Translated by S. Gömeç: 259.

- Nərimanoğlu, K. V. (2004). Türk Dünyası Nevruz Ansiklopedisi (ed.). Nevruz ve Mitoloji. Ankara: AKMB Yayınları. pp. 217–226.

- Bəydili, Celal (2003). Türk Mitolojisi Ansiklopedik Sözlük. Turkey: Yurt Yayınevi.

- Qaraqurd, Dəniz (2011). Türk Əfsanə Sözlüyü. Turkey.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Kalafat, Yasar (1998). Eski Türk Dini İzleri. Ankara.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Günay, Ü. (2006). "Türk Dünyasında Kronolojik Sistemler". Erciyes Üniversitesi Sosyal Bilimler Enstitüsü Dergisi. 1 (20): 239–272. Archived from the original on 2023-08-26.

- Paşayeva, Məhəbbət (2019). Azərbaycanların adət və inancları (XIX–XX əsrlər) [Customs and Beliefs of Azerbaijans (XIX–XX centuries)] (in Azerbaijani). Baku: Azerbaijan National Academy of Sciences, Institute of Archeology and Ethnography.

- Peterson, J. H. (1996). The Festival of Mihragan (Jashan-e Mihragan).

References[edit]

- ^ Lassy 1916, p. 220.

- ^ a b Albaliyev 2022, p. 1084.

- ^ Golden 1982, p. 200.

- ^ Günay 2006, p. 244.

- ^ Musalı 2014, p. 264.

- ^ Lassy 1916, p. 222.

- ^ Lassy 1916, p. 223.

- ^ Fərzəliyev 1994, p. 12.

- ^ Nərimanoğlu 2004, p. 27.

- ^ Azərbaycan etnoqrafiyası 2007, p. 423.

- ^ Acaloğlu & Bəydili 2005, p. 37.

- ^ Lassy 1916, p. 225.

- ^ a b Azərbaycan etnoqrafiyası 2007, p. 420.

- ^ Bəydili 2003, p. 33.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad ae af ag ah ai aj ak Azərbaycan etnoqrafiyası 2007, p. 419-446.

- ^ a b Hacıyeva 2021, p. 121.

- ^ Lassy 1916, p. 227.

- ^ Azərbaycan qeyri-maddi mədəni irs nümunələrinin dövlət reyestri. "Qarayaz" (in Azerbaijani). Azərbaycan Mədəniyyət Nazirliyi. Archived from the original on 2022-03-08. Retrieved 2022-03-08.

- ^ a b Əliyeva 2018, pp. 152.

- ^ Rahimi 2019, p. 151.

- ^ Seyidov 1996, p. 259.

- ^ Azərbaycan qeyri-maddi mədəni irs nümunələrinin dövlət reyestri. "Qarının borcu" (in Azerbaijani). Azərbaycan Mədəniyyət Nazirliyi. Archived from the original on 2022-03-08. Retrieved 2022-03-08.

- ^ "Ordubadda yayın gəlişini də bayram edərmişlər". milli.az (in Azerbaijani). 2 July 2014. Archived from the original on 2023-08-26. Retrieved 2023-08-07.

- ^ Gulnur Kazimova (26 July 2017). "Georgia's Azerbaijani nomads: 'Our people have been humiliated'". OC media. Archived from the original on 2024-03-16. Retrieved 2024-02-17.

- ^ Qaraqurd 2011, p. 63.

- ^ Kalafat 1998, p. 41.

- ^ Peterson 1996, p. 82.

- ^ Price, Massoume (2001), Mihregan (Mehregan)

- ^ "UNESCO assembles peoples around transnational traditions like couscous, one of 32 new inscriptions on its Intangible Heritage Lists". ich.unesco.org. UNESCO. December 17, 2020. Archived from the original on April 28, 2022. Retrieved December 20, 2020.

- ^ Azərbaycan etnoqrafiyası 2007, p. 16.

- ^ Albaliyev 2022, p. 1082.

- ^ a b Azərbaycan etnoqrafiyası 2007, p. 19-20.

- ^ a b Bəydili 2003, p. 326-328.

- ^ Azərbaycan etnoqrafiyası 2007, p. 25.

- ^ Abdullayeva 2007, p. 216.

- ^ Axundov & Kazımov 2007, p. 216.

- ^ Azərbaycan etnoqrafiyası 2007, p. 23.

- ^ a b c Axundov & Kazımov 2007, p. 12.

- ^ Caferoğlu 1956, pp. 66–67.

- ^ Hacıyeva 2021, p. 119.

- ^ Hacıyeva 2021, p. 123.

- ^ a b c d Əliyeva 2018, pp. 145–146.

- ^ Əliyeva 2018, pp. 149–150.

- ^ Khudaverdiyeva 2023, pp. 183–184.

- ^ a b Oymak 2010.

- ^ Najafov 2019, p. 87.

- ^ Mahmud 2018, p. 52.

- ^ a b c d Əliyeva 2018, p. 151.

- ^ Paşayeva 2019, p. 236.

- ^ a b Rona-Tas 1976, p. 175.

- ^ Rona-Tas 1976, p. 176.

- ^ Rona-Tas 1976, p. 177.